Ace Attorney

Written by Takeharu Sakurai & Sachiko Ōguchi

Directed by Takashi Miike

Japan, 2012

I’ll come right out and say it: Takashi Miike’s Ace Attorney, based on the first entry of the popular Capcom video game series, is the single-best cinematic adaptation of a video game property of all time. Now some of the more snide readers out there will no doubt think that this a pretty low bar to clear. There’s at least a partial truth to that: the current all-time champion of video game (henceforth VG) movie critical acclaim is 2001’s Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, coming in at a cool 44% on Rotten Tomatoes (not that the RT metric is reflective of quality in any capacity, but that’s another discussion for another time). While the movie was a watershed moment from a technical standpoint (it had some of the most impressively detailed CGI in movie history up until that point), the consensus was the the film wasn’t engaging enough on an emotional level to be any good. The fact that it went way over budget and single-handedly killed off Square’s film production arm certainly didn’t help matters. As with anything, numbers don’t lie, but they don’t tell the whole truth either.

There exists a very specific kind of received knowledge among civilian (and often professional) movie-goers that tends to oversimplify genre and audience conventions. And like a lot of received knowledge, most of it is problematic at best and flat-out wrong at worst. For example, the belief that all action movies are meat-headed and exist solely to be consumed by only the manliest of men (see also: women and romantic comedies). There is the bewildering notion that movies shot in black and white are only loved by snobby sophisticates, to which I say, have you ever heard of the movie Clerks? But the one that comes up the most often is that if a movie is based on a VG property, it must be terrible. So how is Ace Attorney different? What makes it stand head and shoulders above all comers?

By most accounts, the first major North American VG movie was Super Mario Bros. (Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, 1993). The game it’s based on, released in 1985, remains a milestone in terms of 2D game design and pure gameplay. Everything about this game has reached iconic status over the last 30 years: the music, the sound design, even the levels themselves. By the time the movie came around, five other games were released under the Super Mario banner, including the bulletproof platforming classic Super Mario Bros. 3. Presumably, the people conceiving the film would have been aware that by and large, the Super Mario games were bright, fun affairs that — and this particular aspect is key — didn’t require much in the name of plot to be engaging. If the defining characteristic of movies as an artform is editing, then the equivalent for gaming is interactivity. The throughline between the two media is tone: if you can’t tell the story in the same way given formal limitations, a unifying tone is the key to success. For Super Mario Bros., source, tone, and narrative were colossally mismatched. What could have been a rookie mistake mushroomed into a problem that infected many of the cinematic VG adaptation to be released to this day.

A game’s genre has a direct effect on how smoothly it can be adapted. It definitely helps that the Ace Attorney games are visual novels, and as such have a linearity that fits more snugly in a cinematic mode. Obvious difficulties present themselves when adapting, say, a platformer like Super Mario Bros. or a more abstract, raw gameplay-driven title like Tetris (although this hasn’t stopped the man responsible for the amazingly awful CGI turkey Foodfight! from giving it a try). It also helps that the Ace Attorney games adhere to and toy with larger genre conventions. So, while the interactivity is necessarily lost in the transition from game to film, the visual language of the games (which borrows from courtroom dramas, police procedurals, animes, and film noirs) is still woven together seamlessly in the film. In most other cases, these elements are either kept far apart or awkwardly spot-welded together. Look no further that Patient Zero: Super Mario Bros. had a convoluted plot and looked more like a cheap Total Recall knock-off when it should have been a dirt-simple, brightly-coloured adventure film for kids.

Obviously, no movie will ever be able to do interactivity like a game can (unless you count more avant-garde or non-narrative features, which fall a bit outside of this article’s purview). But first and foremost, Ace Attorney, more than any other VG-based movie I’ve seen, has the same organic rhythms as a game, from tutorial (the introduction sequence where Phoenix Wright struggles his way through an easy case) to mini-boss (the first trial against Miles Edgeworth) to “final round” big boss (the final trail against Manfred von Karma). The problem that many VG adaptations face is this very lack of organic structure; when included, it often feels gimmicky or otherwise shoehorned in, like the first-person segment that closes out 2005’s Doom. Often times, in an effort to streamline the plot to better fit a movie’s narrative structure, game plots get either mangled or outright ignored in their movie equivalents (see: Silent Hill, any of Uwe Boll’s adaptations).

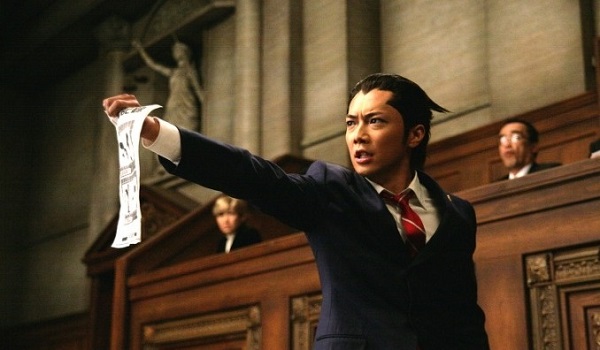

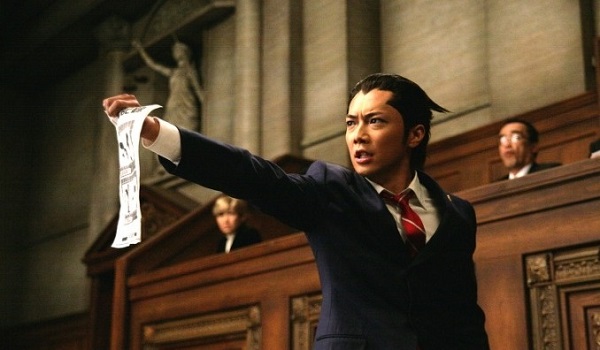

That said, it also helps when you have a master director at the helm who is willing to give the material the treatment it deserves. Ace Attorney is a dense movie, directed with skill by Takashi Miike, and stuffed with a million details that make it feel lived-in. It is also an incredibly well-cast film, right down to the bit parts. It’s a formally vibrant film; next-level cross-fade transitions, tons of background gags, nervy jump cuts late in the movie that parallels a nervous breakdown. In a strange way, this movie reminded me of Alan Rudolph’s Trouble in Mind: there’s at least three decades’ worth of crime movie archetypes in the cast; a major societal paradigm shift has clearly happened, but is never really addressed beyond a few throwaways; everyone’s backstory is really, really sad (although this is played for laughs a few times by master tone juggler Miike). There’s an intoxicating mix of cartoonishness and pathos peppered throughout. Striking that particular balance between freshness and familiarity, fan service and idiosyncrasy, is key to making an engrossing, masterful VG adaptation. Not every game deserves one, and not every director can helm one, but luckily, Miike’s Ace Attorney is a match made in adaptation heaven.

Addendum: That said, it is a crime that this movie is still unavailable on North American home video nearly three years after it was first released, and two and a half years since the festival screening I was fortunate enough to see it at. This might be too out-there for Criterion (although if Criterion does see it fit to put this out, right on), but this would seem like a snug fit for Drafthouse Films, given their distribution of films by a certain other maverick Japanese director. In fact, if at all possible, a double feature of Ace Attorney and Why Don’t You Play in Hell? would be ideal. Just throwing that out there, Drafthouse.

-Derek Godin