Cube

Written by André Bijélic, Graeme Manson, and Vincenzo Natali

Directed by Vincenzo Natali

Canada, 1997

There is such a thing as “pre-critic” movies. These are the films that had a major psychic impact on a writer or thinker way before they have even considered (or even imagined) the possibility of having cinematic sensibilities or intellectual engagement with movies as art-objects. These movies tend to be pop culture touchstones; movies like the first Star Wars film or Ghostbusters or Pulp Fiction are common ones in part because of their ubiquity. But as with all generalizations, there are always outliers and oddities. One of my pre-critic movies, which I saw as a young man of fifteen on Canadian cable on a sunny Saturday afternoon, was Vincenzo Natali’s 1997 sci-fi horror film Cube. To this day, it remains one of my very favourite films, a scrappy little piece of government-funded genre weirdness that gets by on crack direction, weird acting choices, and spectacular sound design.

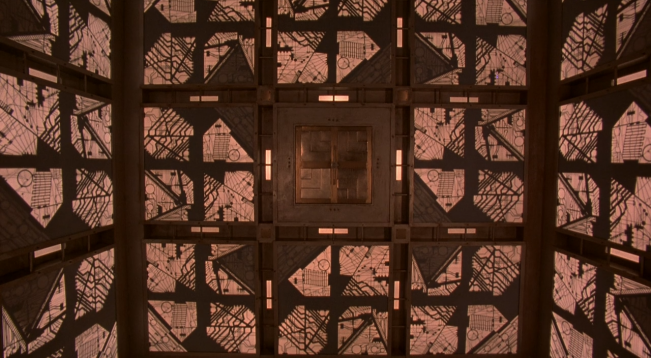

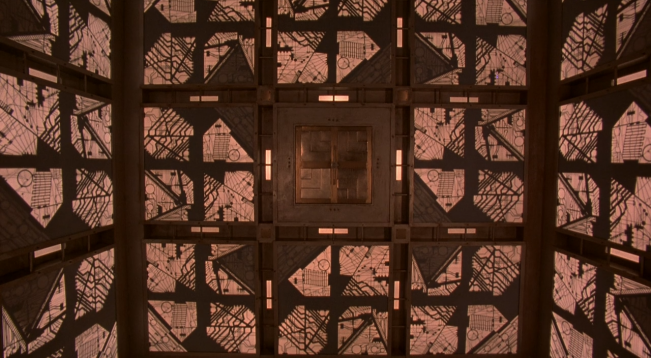

Part of the reason I was infatuated with the film was how it came to be made. It was (and still is) the crown jewel of the Canadian Film Centre’s First Feature Project, made for the price of a small house and shot entirely on a single set. The titular cube’s walls were modular; they could swap out coloured panels to give the illusion of multiple cubes. It was the first time I had heard of a film that was made for so little money using so few resources (this was 2003; Primer hadn’t been made yet and I hadn’t yet heard of, say, El Mariachi). Even in hindsight, Cube is just about as lean as a movie can get while still existing: there are these six people, they’re in a cube maze, they don’t know how they got in or how they can get out, and some of the cube rooms are booby-trapped. Cube is basically 90 minutes of people trying to avoid death traps. Natali gets a lot of mileage from the tension inherent to the premise; this movie probably has the most frayed nerves per minute than any other I can recall. It wastes absolutely no time in establishing the tone of the film. In its truly remarkable first sequence, a man wakes up in a cube, goes into another cube, and in a startlingly graphic sequence, gets diced into a stack of meat cubes, which grotesquely topples over like the world’s grossest game of Jenga, which segues straight into the title card. No dialogue, no credits, just the purest form of diegetic set-up. This is next-level narrative concision, on par with the pulp novels and Twilight Zone episodes the film seeks to emulate.

The acting is hit-and-miss; noted Canadian that-guy actor David Hewlett is enthralling in his surly misanthrope mode, while the presumably-neurotypical Andrew Miller’s casting as a mentally-ill math savant is by far and away the film’s biggest misstep. In fact, one of the film’s weaker elements overall is characterization. This is in part by design: details of the origins of the cube itself are kept to a minimum, and even the slivers that are divulged are left vague at best. While it does make it difficult for an audience to build a relationship with what are basically lab rats, Natali exploits this in two interesting ways to spin it to the film’s advantage. Firstly, from a strictly utilitarian point of view, there is no practical reason to know anything about these characters other than what they know or represent relative to the situation at hand. It’s a clinical and ruthless gambit fit for a movie about existing moment-to-moment in a giant, deadly Rube Goldberg machine. Secondly, while the lax characterization restricts depth, it allows the actors to swap archetypes between each other over the course of the running time. Since the characters exist virtually free from context, these changes feel more like situational adaptation rather than growth. Cube‘s skeletal framework gives the performers a chance to explore the need for certain types of character in a given dramatic arc; as soon as someone starts to lose their marbles, someone else picks up the slack are discovers a new-found sense of levelheadedness. It draws attention to the performances as performances.

Cube‘s lithe build makes it hard to pinpoint ideologically; is it a condemnation of man’s hubris? A tale about trust and redemption? A slasher film where the masked killer is unchecked progress? Movies like Cube exist as a thematic Rorschach test, having as many interpretations as there are people watching the film. Though Natali, not unlike someone like David Fincher, is more interested in the movie as a puzzle box to play with than a conduit for emotions or ideas. This isn’t to say that Natali (or Fincher for that matter) is a cold, unthoughtful director. Rather, he’s a tinkerer, using genre as a way to pick at the inner workings of how movies work. This is why the characters here are sketches. This is why Natali loves trompe-l’oeil visuals, playing with perspective and position seemingly every chance he can get. Despite the recursive industrial nature of the set, Natali manages to get a variety of vibrant, bizarre shots with seemingly nothing more than a camera tilt or a choice perched angle. Part of this is the lighting; everything is awash in dull neons that recall the nightmare version of an office lunch room. Cinematographer Derek Rogers pulls off the impressive feat of making the environment murky without being dirty, basking in a malignant sterility so pronounced that it becomes unspeakably unclean. Add to this some excellent sound design, a discordant tone poem of clanging metal and whirring pistons, and you have the making of a very atmospheric film. Ultimately, even as an avowed fan, there are problems here (Miller’s performance, some wonky pacing here and there, the ill-suiting ending), but they are trumped by the genre-movie treasure trove of goodies included inside. It’s like marvelling at the inner workings of a uniquely deadly pocket watch.

—Derek Godin