Written by A.I. Bezzerides and Robert Rossen

Directed by Lewis Allen

USA, 1947

Perception plays a spectacularly large role in how people behave and process information. Everything one does or chooses to do is at least partly a function of one’s perceived reality. Sometimes, one believes to be doing the right thing whereas they are doing the wrong thing and vice versa. It is but one of the many aspects to human cognition that makes life that much more complicated. It stands to reason that perception can influence how one watches a movie and accepts its terms. These nebulous ideas greatly influence many aspects of the 1947 romance thriller Desert Fury, from what the characters believe to be doing to how the viewer ultimately accepts or rejects the film as a whole.

Chuckawalla, Nevada is home to many people from different walks of life. There is the Haller family, rebellious daughter Paula (Lizabeth Scott) and mother Fritzi (Mary Astor), the latter of whom owns and manages a local casino. There are the upstanding citizens like sheriff Tom Hanson (Burt Lancaster), who has eyes for Paula even though she only sees the officer as a close friend. Finally, there are sneakier personalities prowling around, such as Eddie Bendix (John Hodiak) and Johnny Ryan (Wendell Corey), two racketeers who have nestled on a ranch on the outskirts of town whilst taking a breather from their underground activities on the west coasts. Eddie, handsome and debonair, takes a liking to Paula, who reminds him of his deceased wife. Tom warns her out of jealousy, whereas her mother warns her of Eddie’s advances for reasons that may prove too shocking.

Watching director Lewis Allen’s Desert Fury, it is clear that, as the story moves along, the way in which information is communicated and interpreted, by its characters and the audience, is one of the focal points. Its script, setting, characters photography, and themes come together to make a film that changes tonally and structurally whenever further plot points are revealed. That said, the movie nonetheless feels cohesive, unified, and organic in its storytelling, acting out as a plausible example of how life can easily catch people off guard when they act out against better judgment or advice from others. The fact that it spends a good deal of time on the tenuous romance between Paula and Eddie, specifically during the first two-thirds, may have some thinking that it does not belong in the noir cannon, yet the emotionally powerful conclusion proves just the opposite.

Romantic entanglements are not the only things that distinguish the project. Just like Niagara (which was reviewed a few months ago), Desert Fury was shot in lush Technicolor. Not only was it an event when films were released in brilliant colour in the early 50s (as with Niagara), it was even rarer in 1947. Then again, this is a Paramount picture, and when a major studio truly believes in a project, they make certain to provide the filmmakers all the necessary resources to bring their vision to the silver screen. It does admittedly take a moment or two to grow accustomed to the fact that the film is in colour, although the end results proves worthwhile, less so for the scenes set in Chuckawalla than those in the desert terrains and the aforementioned ranch. The colour photography successfully captures the texture and character of the region in ways that black and white cinematography may not have, or might have done so but in a different way, such as in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre or The Hitch-Hiker. For a story whose scale is relatively small, the cinematography makes Desert Fury feel like a grand, important film.

Pretty pictures aside, the real reason to discover Allen’s film is the methodically woven journey embarked on by Paula, Eddie, Fritzi, and Tom as decisions made by one directly influence subsequent acts committed by another until each has to face emotional truths they would have preferred to avoid. Ultimately, their hopes seem to revolve around Paula in some capacity or another. Tom is evidently infatuated with her although his straight man personality dictates that he should proceed with certain caution in trying to woo her. Fritzi, a controlling if still caring mother, is increasingly frustrated by her daughter’s obstinate counter-maneuvering, from quitting school to wanting to take up a job at the family’s gambling establishment, something Fritzi wants to avoid at all costs. Eddie is the hardest variable to decipher. On face value, he appears to be a reasonably calm, cool and romantic individual, although there is little secret that his history as a crook means he is shunned by just about everybody except his older partner Johnny…and Paula.

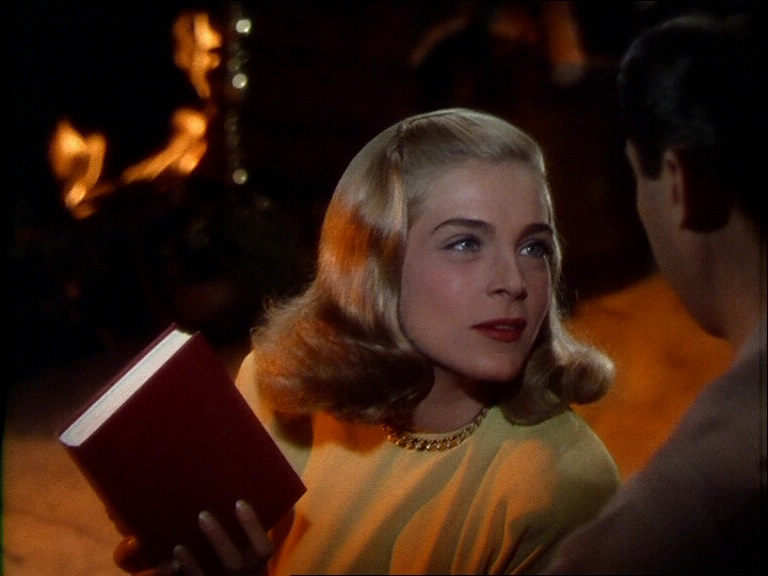

The genius of Desert Fury is in how it does not try to make Paula so obnoxious that she fulfills tried and tested duties of the femme fatale. Nay, Paula, played with exceptional nuance by the lovely Lizabeth Scott, is a three-dimensional, confused young adult. She wants what her mother refuses to award her, cannot see herself end up with Tom, therefore seeks comfort in Eddie’s arms. The manipulations of her closest loved ones are not for evil purposes, but the product of her youthful temperament and the bountiful emotional whims that have her gravitate towards the criminal. Even then, the relationship between Paula and Eddie does not run as smoothly as anticipated given the contrast in temperaments, resulting in a few tense arguments. Johnny bristles at the thought of Paula entering his friend’s life for some key reasons that shall not be divulged here. The key point to make here is that much of what Paula does is performed with one intention in mind, yet provides unanticipated results ensue. Her mother’s warnings, which seemed to emanate from her domineering personality, prove to be not exactly that. Tom’s warnings that seemed to be a reflex of his jealousy prove to be different as well. As for Eddie’s interest in Paula and Johnny’s discomfort, suffice to say that there are plenty of dirty secrets revealed that eventually confirm that Paula, unbeknownst to hers at the time, was the seed of Eddie’s destruction all along, as well as the friendship shared by Johnny and Eddie for so many years. Ironically, in trying to provide the gangster love, she brings out the worst. Once Eddie’s backstory is clarified by Johnny, who at that point can see the writing on the wall, the entire movie up until that point can be viewed through a different lens. Suddenly, Eddie’s ambitions for life with Paula take on a new meaning, as does Paula’s whims and provocations against Tom and Fritzi. Even better, her efforts to find love whilst infuriating her mother are newly understood for reasons Paula herself could not fathom at the time she made her moves.

If there is one thing that, even with the benefit of hindsight, might not sit all well with some modern audiences, it would have to be the movie’s final few minutes after the rip-roaring climax. Seeing Paula do as she pleased, despite fair warnings from loved ones, is easy to accept. She is young and has seen her patience depleted by the figurative walls erected by her mother. Additionally, there is something liberating about seeing an old noir picture in which the rebellious central figure is a women. Knowing her age in the story and the circumstances under which she lives, her behaviour becomes understandable. The closing minutes, however, could easily leave a bitter taste in some people’s mouths however, what with Paula stunned by the turn of recent events and docilely returning to her mother’s arms. A more nuance end to Paula’s journey would have been more fitting rather than make her seem as meek as she does. Then again, perhaps that would have been too much to ask for a movie made in the 1940s.

Desert Fury is a far sharper, subversive piece of cinema than meets the eye. Just when the viewer believes they have the story and character motivations all figured out, Allen’s film has some secret cards up its sleeve. Far from duping the audience strictly for the purpose of offering a thrill, the perceptions are altered because of real constraints that blinded them and the characters in the story.

— Edgar Chaput