Brockovich, her life already a 24-hour job trying to raise three children as a single mother, is involved in a car accident after being denied yet another job. After approaching ambulance-chasing lawyer Ed Masry with a straightforward case, Brockovich loses for her crass behavior in the courtroom. By funneling her sex appeal and righteous mother-centric zeal into Masry’s law office, she straddles him to accept her to work there with no law experience, handle a case of chromium poisoning from the water supply on her own, and use the full extent of the office’s power to chase a corporate conspiracy. As her focus becomes increasingly more career-driven, her parenting is taken over by George (Aaron Eckhart), a new neighbor and motorcycle enthusiast who wishes for Brockovich’s affection, only to receive it between her research sessions and client visitations. As the evidence mounts against PG&E, Brockovich pushes Ed to pursue until every client can be compensated, solidifying her as a politically-charged local hero and a charismatic legal clerk extraordinaire.

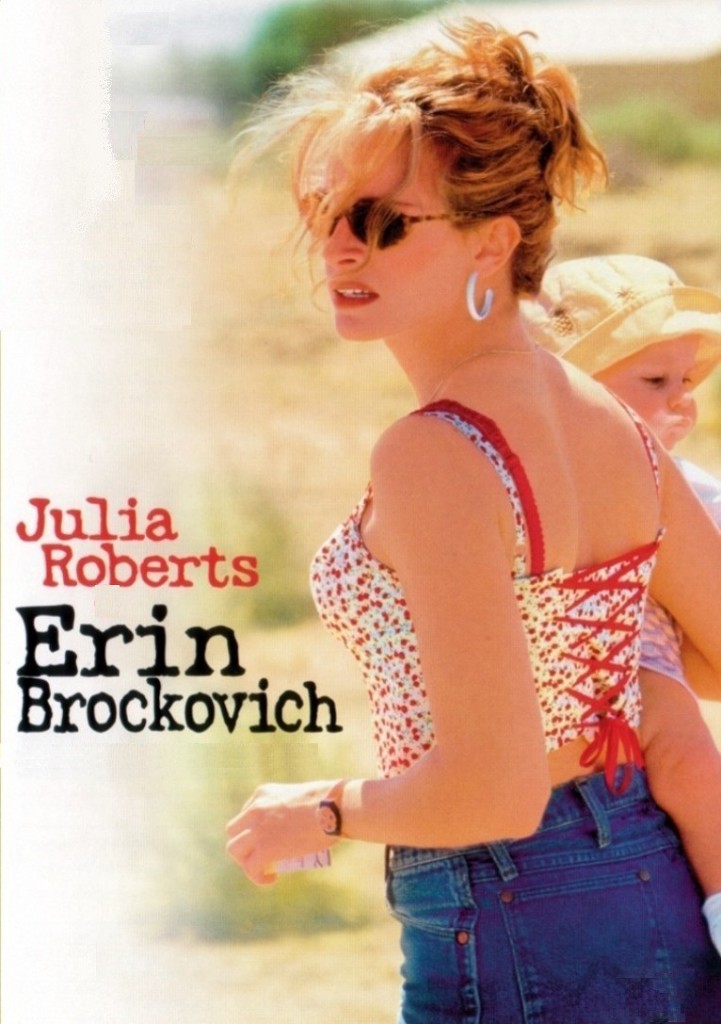

It is a standard fare kind of narrative — the protagonist is forced to choose between family and career, manages to find the right sort of balance, and uses the newfound confidence and clarity to win her battle. This is galvanized by the title at the beginning claiming its basis in reality, but still manages to divide audiences between accepting Soderbergh as a spineless Hollywood hack turning easy scripts into cash or a compelling, sentimental ride on some of Hollywood’s most proud tropes. It was certainly not the start of the “Hollywood-to-personal” filmmaking cycle pegged on Soderbergh, but it may have established this lens for those intrigued with the rising figure. However, Susannah Grant, having previously written scripts with powerful female leads such as Pocahontas and Ever After, wrote Erin Brockovich to place its headlined figure on the big screen as a sort of sui generis lower-middle class Bulworth retaining a self-motivated yet public-spirited sense of political belonging. If the vehement figure of Brockovich could leap from the pages and place spirit into what may be perceived as standard fare, Soderbergh would not glance over this opportunity to bring her to film. If the film were to singularly study its protagonist, only someone with timed vitality and star power could fully adapt Brockovich’s presence and cultural mythos. Thus, Roberts, the name on the poster, DVD, commercials, and every promotional material available, was attached to the project. She is perfect — almost too perfect — in her execution of melodrama to the extent that others quickly accuse her of showboating, of playing Julia-Roberts-who-is-definitely-going-to-get-an-Oscar-for-this, than Erin Brockovich. This spawns a different conversation — should a a star have to play down their own attributes when firmly in a role they exemplify? The same reaction has been ascribed to the astronaut Matt Kowalski in Gravity not being played by George Clooney but being George Clooney. When Robert Downey, Jr. played Iron Man, audiences soon supplanted the actor within the superhero: Robert Downey, Jr. does not just play Iron Man; rather, audiences have accepted Iron Man as being Robert Downey, Jr. However, Roberts’s case is more interesting given the “based on a true story” perspective — namely that there is a real Erin Brockovich out there and perhaps Roberts has some responsibility to accurately portray her.

The character of Brockovich is complicated — she can come off as an asshole, insulting a law office secretary for her weight and sexually manipulating the clerk of the water board for access to their documents. For the audience to be able to connect with Brockovich instead of holding her in anti-hero status, these faults need to be played out via a collaboration of Roberts and Soderbergh. Roberts plays Brockovich as sassy, defensive, and spiteful only to an extent and always with her external pressures to do so visible in the lines of her face and body gestures. Soderbergh crafts her persuasive sexuality to come from a personal tic, originating in the power she obtained with her looks in becoming Miss Wichita. The most quotable line from the film is a response to Ed’s questioning of her prerogative power: “They’re called boobs, Ed.” This would almost devise a problem for Brockovich, posturing her as the archetype of troubled-past sexual-aggression that weakly traverses the narrative as a feminist conclusion without an argument. Instead, Roberts’s archetype, purportedly funneled from the “golden-hearted hooker” character from Pretty Woman, embodies sassiness as a confident hallmark, using it when necessary and as a subversive atmosphere when not. As the case accelerates, Ed calls in a big-city law team to handle the formalities; Brockovich is furious as she feels that she maintains legitimate ownership of the case and that the people of Hinkley will not respond to formal tactics. Her curvy outfits disrupt their expectations as she vocally lists phone numbers and complicated personal information of various clients from memory, solidifying herself as the case’s paramount authority. While Soderbergh places keen adjustments to a well-known paradigm, the film ultimately becomes lost in a motherly sentimentality, making Brockovich a messiah figure for the residents for the residents of Hinkley sans unconditional love; her emphasized “I just want to be a good mom” monologue in the beginning now appropriated for the cancer and disease-ridden town. It is a nice gesture and a definitive comment on the parent/career dilemma, but it is troublesome to accept given Roberts’s previous performance of a woman whose life has finally been given purpose via her career. Her reconnection with her kids at the end of the film also suffers; they accept her social-ladder-climbing by relating to the sick kids with whom she is actually spending time — no real catharsis, just narrative happy-ending excuse, an emotional deus ex machina.

In June of this year, the real Erin Brockovich made a small appearance in the news, being arrested for boating while intoxicated. As a minor celebrity involved in a minor affair, she received a minor spotlight, but to those familiar with Erin Brockovich and Erin Brockovich, it is hard not to imagine Julia Roberts, bikini-clad, stammering her way to the bow and manning control as she did in the PG&E case. Such is the power of resolute stardom — an intermingling with reality and the exemplification of type, a mirror, or stand-in. Soderbergh is a director fully aware of the conversations surrounding archetypical acting and utilizes them, for better or worse, to invigorate the film’s space and leave a cultural imprint long after its theatrical run.

-Zach Lewis