March, 2011: After their rights to the source material elapse after a failed four year venture, Paramount officially drop their in-development film Dune, ending a frustrating and ultimately fruitless effort that served better as a topic of heated discussion than an actually feasible movie.

Such an announcement had been on the cards, and the prospect rightly feared for months. Aside from the consensus that Frank Herbert’s epic, 1965 science fiction chef-d’oeuvre will never again make it to the big screen, the proposed project was in a state of flux from the moment it appeared on the radar, with each change of personnel seeing the release date pushed further and further back.

The ‘film’ still has its own page on IMDb, albeit a rather scarce one. There is a name, the year 2014, but no director, no writer, no other entries. Aside from providing a portal to forum conversation about casting and narrative focus, it serves no purpose. It increasingly looks like it never will.

For various reasons, the proposed Dune remake/rethink/reboot has been cited as a doomed enterprise from day one, whether it be because David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation was such a critical and commercial disaster, or due to the sheer depth of the material, or as a result of its religious and political undertones making it inaccessible to a wider, more casual audience. Fanservice only makes so much money, and the expected outlay would tip the scales deep into the red.

But the mystery remains as to why, in an era in which Hollywood is rushing novels big or obscure into the adaptation treatment room, one of the most critically acclaimed and popular novels of the 20th century, one of the most visionary pieces of science-fiction ever produced, is still seen as untouchable.

Arrakis – Dune – Desert Planet

Ever since Herbert scribed the novel, and its ostensible sequels Dune Messiah and Children of Dune, there has been a clamor to have its grandiose story and rich background mythology brought into the cinematic fold, and little wonder. It has been voted as the greatest science-fiction novel of all time in several polls, won the Hugo award upon its publication, and has sold over ten million copies since its 1965 release. And, though popular for its mosaic of subplots and diverse symbolism, Dune has at its heart a classic hero’s arc.

It is the story of Paul Atreides, heir to the noble house Atreides, in a complex and cynically sinister future 20,000 years in the making, one with medieval-style machinations and various organizations and clans resembling, among others, the Spanish Inquisition. The family is awarded a contract the universe’s Emperor to occupy Arrakis (better known as Dune), a sparse desert planet which is the only source of a priceless chemical known as spice melange. This deal turns out to be a trap, and the Atreides family is wiped out by their rivals the Harkonnens, with some covert assistance from the Emperor. Paul and his mother Jessica are the only ones to survive, and are forced to bed down with the planet’s natural inhabitants, the underground dwelling Fremen, and Paul leads an uprising against his new people’s oppressors, fulfilling his destiny and becoming the new messiah, a living God, in the process.

While the basic framework outlined here is dense as it is, it doesn’t take into account all of the background. Herbert crams in enough detail, cultural nuance and general story framing material to fill several apocryphal historical texts. Virtually every character has an agenda or scheme, with the recurring phrase ‘plans within plans’ quite apt. It is an inter-galactic chess game set in a universe that marries Roman empire-esque debauchery and lavish living and futuristic cloning and resource politicking.

The difficulty of approaching such quantity with any form of pragmatism is best illustrated by the book’s previous screen incarnations, and the lost chances along the way.

Lynchianism, Serialization & Pink Floyd

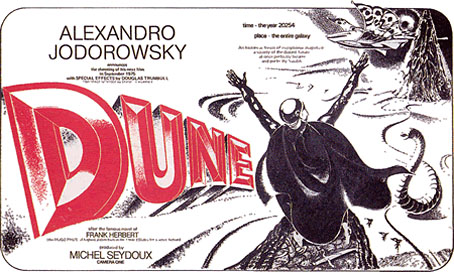

In 1974, a botched first effort at adaptation was made by a French consortium who had procured film rights from Herbert, which brought in Chilean-French Director Alejandro Jodorowsky. His mooted effort would be unconventional to say the least; Salvador Dali portraying Emperor Shaddam IV, Orson Welles as the Baron Harkonnen, Jodorowsky casting his son as Paul, artwork designed by HR Giger, soundtrack by Pink Floyd and an estimated running length of fourteen hours. Perhaps predictably, this project collapsed. The end result was a “life changing” experience for Jodorowsky, and a stint in a psychiatric hospital for screenwriter Dan O’Bannon (who would later pen Alien).

When the rights expired, they were quickly bought up by maverick magnate Dino De Laurentiis, and Ridley Scott was brought in, with Giger retained. This set up lasted seven months before Scott dropped out to take up Blade Runner instead. Scott’s original plan had been to break the story into two films, a creative compromise that seemed to be a highly practical solution. However, the war of attrition that was pre-production drove him away.

It wouldn’t be until 1981 that progress was made, when on the strength of The Elephant Man, oddball auteur David Lynch was picked out by De Laurentiis’s daughter Raffaella. This came despite the director having no knowledge of the subject matter, or any interest in science fiction. Three years later, the finished piece arrived, on the back of the success of the Star Wars trilogy and boasting a serious budget and strong supporting cast.

It was a mess for all concerned.

The film bombed at the box office, and was slaughtered by the critics. Production wrangles saw Lynch all but disown his work, even Alan Smithee’ing one of the released cuts, and avoiding mention of the project in later interviews and press material. The only person who had a positive word to say, ironically, was Herbert, who believed that for the most part it was faithful, albeit not closely. The main flaw, incidentally, of Lynch’s version was that while it deviated from the book’s story, it also relied too heavily on its background, becoming unintelligible to those not versed on Herbert’s work. Almost impressively, both casuals and fans were alienated.

It’s hardly a surprise that nobody wanted to touch the material afterwards, and there was clearly going to be no attempt made towards providing a mooted sequel. The novel had been subjected to attempted adaptation for eleven years, and when it finally to fruition, the message was clear: “Dune can’t work as a film”.

A more noble, though modest, effort was launched in 2000, which saw the Sci-Fi channel produce a three part mini-series with Alec Stewart as Paul and William Hurt as his father, Duke Leto. It was warmly received and affectionately made, a more honest small screen venture dedicating more time to the material. Herbert himself never got the chance to see it, of course. He passed away in 1986, with his son Brian and collaborator Kevin J Anderson continuing the series based on notes discovered after Herbert’s death.

Troughs and Bergs

In 2008, Paramount announced their intention to revisit the novel and produce a “faithful” adaptation, with its themes inspired by current events in the middle-east. Peter Berg was attached to direct, despite the part time actor’s lack of experience on ‘big’ features, supposedly compensated for as Berg was a ‘fan’ of the novel, and passionate about making the project work. A draft by Joshua Zetumer was provided as a blueprint, while Paramount provided a healthy budget maxing out at $175m.

Little over a year later, Berg dropped out with the intention of turning the board game Battleship into a film, once again amid claims that pre-production was taking too long and that scant progress was being made to actually filming anything. Incidentally, Battleship is to be released this summer, and looks as grand as it does overwhelmingly stupid.

Paramount took immediate action, intending to shortlist Directors who had an appreciation and understanding of the book, passion for the project, and would be able to stick to the financial constraints. District 9 creator Neill Blomkamp was immediately installed as favored first choice, while British horror specialist Neil Marshall impressed with his approach and ideas. However, in January 2010 it was Taken’s Pierre Morel, protégé of Luc Besson, who was placed at the head of the tree, basing his work on a script by Chase Palmer. This lasted about five minutes before Morel “stepped back”, instead taking a Producer’s slot. It would be the last tangible movement, and last year Paramount officially dropped interest when the four year contract elapsed.

Just like the long period of inactivity and frustration that preceded the Lynch odyssey, a lack of positive steps or clear intent to actually do some shooting had scuppered the deal.

For fans, it had been just a long period of false hope full of talking over action, one that was sealed with a damning indictment of Hollywood’s inability to come to terms with the material. The idea of a satisfying, fitting movie bearing the name Dune increasingly looks like the Holy Grail.

Making it Work

So what’s so hard? After all, if Lord of the Rings can make it to screen, and be so successful in the process, why can’t Dune? A space set Sci-fi epic would be sure to make a bomb if promoted well, and relying on word of mouth. Think Avatar, the soon to be released Prometheus and, hell, even Star Wars and the insipid prequels. Add in plenty of fans of the franchise, some viral marketing and considering the spectacular visuals that are assured, there’s plenty of room for interest.

Plus, in the form of the 1984 version, we have the perfect trial by error, a full big budget experiment to show what should be avoided, what should be retained; the good and the bad.

Comparisons to Lord of the Rings are actually quite appropriate, given the scope. LOtR was a trilogy because there was simply too much to fit into one film. This presented its own problem, of course: Money. One film would be costly, three is gargantuan. Any financer would be making a career defining gamble putting so much green to the idea, just as they did with Peter Jackson’s ambition and ultimately staggering success.

But one positive point of reference to come out of the Tolkien adaptation was that the first part ended on a low key, a cliffhanger of sorts that served as a buildup to the rest of the three-parter, and got away with it. Looking at the trilogy, The Fellowship of the Ring is essentially nothing more than a set up for the real action presented in The Two Towers and Return of the King. The anticipation was such that this motion was seamless and no damage was done.

Which brings us to what Ridley Scott had intended in the late 70’s: To take Dune and turn it into two films, with the break likely coming at the end of the first part. At this point, the Atreides house is in ruins, and Paul and mother Jessica face an uncertain future amidst the native Fremen. The famous cry “the sleeper has awoken” could serve as the perfect cutting point, with the second film focusing on the battle for Arrakis and the uprising leading all the way to the throne. Certainly, the novel builds up to this point with such crescendo that it would be a fitting climax to a film of such scale. The follow up would be mouthwatering by the time the end credits rolled with a teasing “to be continued”.

Whether it be one or two parts, Dune would also require, as the Paramount mandate demanded, a Director with intensive knowledge of the novel and also the willingness to make it work, while sticking to budget. It would far too easy to focus on the visual aspect of Dune, and the very dry unfolding of the plot, and in the process ignore the significant emotional weight of the material and the sublime framing of characters large and small. Herbert’s love for the players in his gloriously mounted tale plays a huge part in its immortality.

Favorite characters among readers range from Paul (pre or post Muad’Dib), Jessica, Duke Leto, down to comparatively smaller figures like Duncan Idaho, Piter De Vries and Thufir Hawat. In fact, one of the book’s most complex and compelling characters in Feyd Rautha, an antagonist utterly defiled by Lynch’s version, played by Sting and with absolutely no personality other than “enjoys being evil”. Anyone taking up Dune would be forced into taking backbreaking strains in order to balance the plot, the characterizations, the themes, the extraordinary visuals and the mythological and modern symbolism. Such Directors are hard to come by, and any wish list would be filled to the rafters with ‘ifs’ and hypothetical pondering.

Even with potential total length of 5+ hours, the films would also have to make serious decisions about some of the branching subplot storylines, such as the parts played by the Fenrings (a lord and lady tampering in genetic engineering), Irulan (daughter and heir to the Emperor) and the myriad of organizations and orders conducting conspiracies and shady dealings in the background. Lynch’s film dropped the Fenring plotline, and subsequently lost a huge part of Feyd’s significance. Such is the delicate nature of editing, where removing one seemingly superfluous plot strand fatally damages another, then another, then another.

It all comes back to Paramount’s original pledge: staying faithful. The explanation of the development hell that lasted four years is that it is borderline impossible to remain true to the book and still condense things down to two and a half hours. Fretting and deliberation concluded to the sum of nothing. And this isn’t taking into account the other problems.

Chief among them is casting. While the supporting cast could undoubtedly be filled out with top class actors paying service to some varied and fascinating parts, finding the figure to portray Paul Atreides is at best problematic, at worse a plea for miracles. It would require an actor who could convince as both a sheltered, regal teenager and then as a desert warrior and leader of men. While Kyle MacLachlan and Alec Stewart hardly embarrassed themselves, neither quite brought the weight required. A transformation akin to Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone would be required to pull of Paul’s arc. Simply put, any actor able to do the role justice would be producing one of the greatest ever acting performances.

Supposing any prospective filmmakers could get the balance right, retaining the heart and arteries of the novel and nailing down the men and women required to perform the operatic story, who would pay for it? And what visionary director could stay true to the material in all its forms, and yet still make it economically viable? How could any scriptwriter hope to bring the mountains of information and misinformation and deliver a feasibly workable final draft? Would the millions who queued for tickets understand it?

Unobtanium – Impossible Material

The sad truth is that most of the questions above are most likely answered by awkward silence. Cynical as it may be, the general opinion post-release in 1984 seems to hold true even now.

One of the most cinematic novels of all time cannot be made into cinema; the transition is too complex and too fragile to be coordinated by anyone other than a genius. Unless something truly extraordinary takes place behind the scenes, there will be no second go of it.

A barren IMDb page houses a select group of fans still debating the merits of Liam Neeson as Duke Leto and Kevin McKidd as Emperor Shaddam, but such imaginative conversation and thoughtfulness is likely the closest these people will ever come to seeing it occur. Perhaps it is for the best; after all, what could be worse than a travesty of an adaptation, one that tarnishes the image of the book?

The franchise instead seems to make more ground in other fields, and has proven more successful in a merchandising field that has produced board games, card games, and five video games that range from role playing to real time strategy, as well as non-canon additions to the book series.

Reactionary though it may be, there is still a lingering sense of bitterness that while Dune is a tome to be revered but never mounted, this year sees Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter and The Hunger Games hit screens, while 2013 will welcome Pride and Prejudice and Zombies and another round of Stephanie Meyer inspired teenage angst posing as supernatural drama in The Host. Are these novels really more worthy of time and money? The combined budgets and man hours alone could be redirected towards sand worms, gom jabbars and the power of a word. Alas, wishful thinking. A combined total of fifteen years of failed efforts provide the precedence, as does one failed film.

But we can always dream. After all, to quote the novel, “accepting one little death is worse than death itself”.