Far be it from me to disagree with our staff, but I would hard-pressed to name 30 films from 2015 that I would consider among the “best” of the year.

The same can’t be said for film music, though. As predictable as each superhero template or franchise reboot may have been this year, composers keep finding new ways to reinvent the sounds of the cinema. Not to mention that the ever-widening landscape of VOD and streaming service-produced projects has increased the room with which artists can flex their musical chops.

2015 was an embarrassment of movie score riches. In indie horror gem Bone Tomahawk, Jeff Herriott & S. Craig Zahler inject hope and despair into a bleak, cannibal-stricken Wild West, where feeling anything is better than the unflinching mortality facing its characters. Patrick Doyle’s warmhearted Cinderella continued Disney’s tradition of attaching amazing scores to frivolous live-action do-overs, while on the other end of the spectrum, Anomalisa depressed the living crap out of us with a sodden mixture of urban malaise.

On the international front, Qigang Chen reunited with Zhang Yimou in Coming Home with a tender, aching turn, and Lim Giong gifted The Assassin with serenity and martial drums in equal measure.

Like any discussion of quality film music, context is always key, which means leaving off the excellent, party-friendly electronica of Turbo Kid and Philip Glass and Marco Beltrami’s Fantastic Four, an impressive collaboration that’s better served in a picture that still knows what it wants to be.

As these close-calls suggest, narrowing down the year’s best film music to 10 choices is a daunting task. So with that in mind, take a look, and share your own picks in the comment below:

10. Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter — The Octopus Project

This zonked out pseudo-odyssey is a beast of its own, and the Zellner Brothers probably like it that way. David and Nathan Zellner are no stranger to telling arresting, emotionally-stunted stories about society’s unwanted, and Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter only reinforces that. Kumiko follows its title character from Japan to North Dakota to dig up the buried loot from Fargo (yes, really). Austin’s The Octopus Project sees to reinforcing Rinko Kikuchi’s bizarre whim of a trip. Fuzzed out and chilly textures blanket the snow-laden trek, blurring direction and motivation with a blizzard of unease. Livelier sections energize an ill-conceived set of travel plans. “Bunzo,” named after Kumiko’s scene-stealing pet rabbit, adopts an anachronistic medieval procession with bungeed percussiveness. The Zellners never settle the score on if the Coens’ crime thriller plays a reality in the film’s own world or even if what we’re seeing is real at all. The music doesn’t care either, validating this one-woman RPG to dizzying new levels.

9. Steve Jobs — Daniel Pemberton

“Musicians play the instruments, I play the orchestra.” The former is immediately clear in Daniel Pemberton’s score for Steve Jobs, with its first cue literally rustling the orchestra’s instruments awake. Whether or not one agrees with Steve Jobs’s self-assessment might depend on more than what brand of tablet they last purchased. Director Danny Boyle and writer Aaron Sorkin segment the Apple co-founder’s biography into three sections, moving from the highest highs with the launch of 1998’s iMac to the lowest lows in the ill-fated conception of Jobs’s NeXT computer company. Everything eventually dissolves in unbridled applause for a controversial figure in the tech industry. Before the delusion sets in though, Steve Jobs is intent on getting inside its central figure’s head. Pemberton works with cool reserve and white knuckle dramatics, popping up in one of Sorkin’s patented walk-and-talks or crescendoing to an empty stage. Its textures even match the script’s time-hopping asides, enlisting overtly classical or reserved modernism whenever required. When paired against petty arguments about 90-degree angles and design nitpicks, it becomes a comically bloated affair. Even compared to his biographers here, the highest opinion of Jobs may have been the “conductor’s” own, but one thing’s for sure: he’s certainly leading Pemberton’s orchestra.

8. The Duke of Burgundy — Cat’s Eyes

Peter Strickland’s hypersexual tête-à-tête between two entomologist lovers is intimate to the point of suffocation. Academic lectures dissect nuances in insect anatomy, magnifying Sidse Babett Knudsen and Chiara D’Anna’s field of study — which is entirely devoid of male players — to an inescapable proximity. Not to mention the pair’s indulgences in BDSM have eclipsed whatever their relationship once resembled. The entire affair might be too off-putting to stomach without Faris Badwan and Rachel Zeffira there to lead us by the hand. Their dusky palette of ghostly choirs and seemingly endless reverberations haunt a romance that already feels doomed to mistrust. Like the leather-clad roleplaying that D’Anna comes to obsess over, there’s also a beauty in the music’s alienation. Cat’s Eyes spin ballads that stretch for miles with synthy curlicues and featherweight instrumentation primed to wander off like some woodland nymph. It’s a siren song worthy of the crippling metamorphosis that awaits.

7. Star Wars – Episode VII: The Force Awakens — John Williams

Star Wars has always been about repetition and variation, finding meaning (or monotony) in recalling the touchstones of its pan-cultural galactic mythology. That once held true for the franchise’s music, but for his seventh score in the series, John Williams varies more than repeats himself. Dominating familiar themes with rich walls of sound, Williams’ new music is as clouded and uncertain as the intergalactic politics and the Force’s new status quo. The Resistance receives a mobile, upwardly chromatic march and conflicted Darth Vader poseur Kylo Ren has an appropriately inconspicuous five-note signature. Like the character though, the music for Rey is really where it’s at. Williams introduces a new glassy theme for Star Wars‘s would-be heroine that’s as big of a musical game-changer for the saga as “Duel of the Fates.” The Force Awakens isn’t chock full of greatest hits, and with all the fan servicing and borrowed plot threads, that’s a relief. The series is back and it’s brought uncertainty, stakes and danger with it. For the first time in decades, a galaxy far, far away feels exciting again.

6. Inside Out — Michael Giacchino

Michael Giacchino and Pixar were always meant to be. Some of the composer’s best work can be counted among the animation studio’s greatest hits, from The Incredibles to Up, the two balance whimsy with universal themes of disappointment and loss — and with their latest success, an understanding that those crummy feelings are completely okay. Imaginatively realized as a kid-friendly Inception, Inside Out illustrates the inner turmoil of Riley, a young girl whose emotional center is disrupted when her father takes a job miles away from their Minnesota hockey pond, hauling the family out to foreign territory in the Bay Area. Riley’s emotions take center stage, distilled into sentient forms as Joy, Fear, Anger, Disgust, and Sadness, and Giacchino accompanies their race from one charming high concept to another. His compositions forego basic motives for each emotion, opting for a rich tapestry that bobs and weaves along with emotional cyphers that wear their hearts on their sleeves. From Riley’s bustling central “Headquarters” of her brain center to the darkest depths of the Memory Dump’s forgotten pieces, Inside Out’s music approaches the good and the bad, the ups and the downs, the Bing Bongs and the Sadnesses with an open mind and a full heart.

5. The End of the Tour — Danny Elfman

“You’re trying much too hard to make your world seem like a dream,” sings Felt’s former frontman Lawrence. From the British alt band’s “Sunlight Bathed the Golden Glow” to poppy reverence for Alanis Morissette, The End of the Tour‘s soundtrack is inspired by the very music journalist David Lipsky and author David Foster Wallace listened to during their 1996 Rolling Stone interview. And its score is even better, with Danny Elfman weaving the deep cuts and crate digging into his cues. “Room of Books” teases out the chorus of R.E.M.’s “Full Circle,” and traces of “The Big Ship” turn up in the melancholic “The Tour’s Over” — despite Eno’s track itself functioning more or less as its own perfect music cue in the film. The interspaces between score and alt-rock playlist become indistinguishable from another, perfect for a story about persona and craft — and how both can feel inextricable from one another. That’s a running frustration for both Wallace, whose struggles with fame are wonderfully realized by Jason Segel, and Lipsky, a starving author himself faced with a far more brilliant soul as his interview subject. As the music in The End of the Tour shows, maybe it doesn’t matter where the genuine ends and the facade begins.

4. Queen of Earth — Keegan DeWitt

Timo Chen may win 2015’s award for “Best Use of a Sex Toy in a Film Score” for his vibrator-employing music in Advantageous, but Keegan DeWitt’s ingenuity went unparalleled in its application. Blame the “wrenchenspiel,” the glassy apparatus the Wild Club band leader jimmied up for his haunting turn here. As the sound of a slow creep propelling a hundred little voices inside Elisabeth Moss’s head, the score twists and turns the ordinary into the extraordinary, morphing into a soundtrack that unravels in its character’s own headspace and her hot-and-cold relationship with bestie Katherine Waterston. Concurrent rhythms make for a distracting, enervating experience, plunking and picking away with an (eventually) alien nature. DeWitt and director Alex Ross Perry’s previous collaboration in Listen Up, Philip kicked open the doors to the stuffy offices of its haughty misanthropes. Queen of Earth is a subtler, more deliberate creature. It chips away gradually, only to find that what it was digging for isn’t something it wanted in the first place.

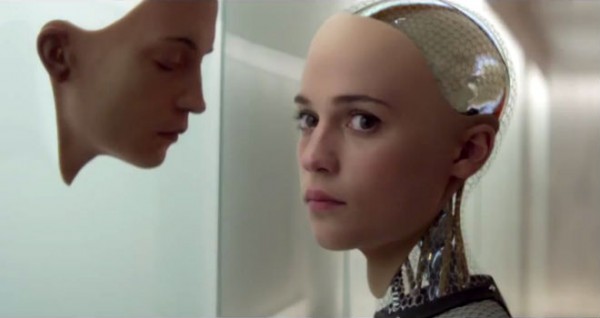

3. Ex Machina — Ben Salisbury & Geoff Barrow

Like its wonderfully-realized android, Ex Machina does not mess around. We don’t know this at first because Alex Garland is committed to germinating a profoundly human story around Alicia Vikander’s A.I.. Likewise, Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow’s digitized score. The pair play right to Domhnall Gleeson’s guinea pig, as he’s assigned to test Vikander’s prototype designed by a genius but eccentric recluse (Oscar Isaac). Quite simply, Ex Machina sounds fake but feels real, its music bubbling into being from nebulous ambience and murky synth textures. Compared with It Follows, which uses a similar musical approach for a fun, but one-dimensional throwback, Barrow and Salisbury have injected a real soul into their work, drawing out an underplayed spirituality with familiar instruments like piano. The final conclusion may be swift and brutal, but its music thrives on the possibilities of the story’s premise, realizing a wondrous, unique life from a synthetic landscape — and in gloriously slow-burning fashion.

2. Carol — Carter Burwell

After taking the year off to score Olive Kitteridge, Carter Burwell came back in 2015 and had himself quite a year. Between his five film scores, Mr. Holmes seems destined as Oscar bait come awards time, and Burwell’s music for Anomalisa is the most subtlly depressing thing you’ll hear all year. It’s his music for Todd Haynes’ tragic romance however where he really shines. There’s plenty of tragedy in Burwell’s music, with somber, sunsetting chamber arrangements and delicate, reflective piano. Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt was an anomaly, even for its pulpy relegation at the time, for a rosier-than expected outlook on an otherwise doomed relationship. Burwell adds to that kernel of hopefulness with an exquisite, piano-driven motive, moving upward in scale-like fashion as a sudden rushed figure offsets the sounds of Cate Blanchett’s socialite falling in love with Rooney Mara’s shop girl. Burwell’s melody has a glorious hopelessness to it, one that drives and stumbles while somehow maintaining grace in the end.

1. Mad Max: Fury Road — Tom Holkenborg

What else, right? It’s not that Tom Holkenborg’s score is best because of its variety — although it certainly has that. Fury Road towered above all other film music in 2015 because it controlled the uncontrollable. Cues like “Storm is Coming” are so menacing in their unpredictability; that they come before such classically-serene cues like “We Are not Things” and sound like one and the same is the real achievement. George Miller’s brilliant return to blockbuster filmmaking brought an unparalleled level of anarchy in tow, most notably a caravan of musical insanity where anything goes and everything works. Heavy metal. Electronic dance music. Flares of Hans Zimmer-styled bombast. Good scores complement their pictures first and foremost. The music of Fury Road is so indelibly tied to its picture that any listening experience can’t help but recall the images it’s been so traumatically branded onto. Ride on, Tom Holkenborg. Shiny and chrome.