The concept of the sci-fi horror genre allows us to address the built-in terrors and tensions developed in society that are difficult, if not impossible, to actualize and confront directly. It has the strengths of sci-fi’s ability to question our potential as a developed species, breaking current conceptions of reality to attain a scenario that directly addresses these bigger questions than those enveloped in regular drama. However, some of these questions are big enough to be menacing: we do not always wish to wonder about the scientific possibilities that lie outside of us; the unknown of the natural world can do its best to terrify us as well. This is a major distinction between what sci-fi horror and “regular” horror intend to achieve: no longer are the monsters personal and haunting regular people; they can be cosmic and haunting our professionals, our perceived authority. It is the helplessness in face of the unknown that scares us in all horror, thus leaving the sci-fi horror genre in a unique position to give a sort of therapy to humankind’s universal fears.

3. Tetsuo: The Iron Man

Written and directed by Shinya Tsukamoto

Japan, 1989

By the end of the 80s, the global interest in Japanese filmmaking had died down, as members of the turbulent Japanese New Wave (Yoshishige and Imamura, for example) had become politically passive in their cinematic output, while what little interest they maintained was funneled through an exclusive festival scene. Enter Shinya Tsukamoto’s low-budget genre-fueled passion, crafting Tetsuo: The Iron Man as the creative child of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner and David Cronenberg’s Videodrome, which excited both the Japanese film industry as well as an American market craving a reboot of unique genre film. Tetsuo is inextricably linked to its economic history, spawning much of what we know of J-Horror, but it is no blockbuster — it is independent genre filmmaking at its purest, delving into questions of how humanity relates to technology and society while emitting a deeply frightening tone through its formalist approach.

A character sometimes dubbed “The Metal Fetishist” (played by Tsukamoto) is run over by the Man (Tomorowo Taguchi), tossed into a forest when presumed dead, and subjected to accidental voyeurism of the Man and his girlfriend (Kei Fujiwara) making love, thus linking ideas of metal and sexuality for the Metal Fetishist, to be used in his ultimate revenge upon the Man. The film fixates on the Metal Fetishist’s grotesque, parasitic invention made of vaguely organic yet mostly iron materials that eventually secures itself onto the Man, transforming him into a Cronenbergian steampunk kaiju able to somehow be controlled by the Metal Fetishist’s powers. The film distances itself from hard sci-fi, yet still concerns itself with the role of technology, a theme present in most if not all science-fiction, and how it relates to what makes us human. In Tetsuo‘s case, it is a relationship of this technology with sexual intimacy: subtle metaphors are damned as the Man’s penis is literally transformed into a drill, penetrating and killing his girlfriend as vengeance for their sexually charged actions against the Metal Fetishist. The film ends on a final note of intimacy, as the gruesome metals of the Metal Fetishist and the Man become fused, resulting in a literal technological connection between the men that resolves their earlier primal instinct to fight to the death. As anyone would do in this situation, they thus aim to take over the world.

Although just as easily placed within genre conditions for body horror given that the distortion and focus on the body is what makes it horrific, Tetsuo also easily lends its focus to the urban areas surrounding the narrative. The man is first attacked in a subway station; the camera races past metropolitan architecture when shifting perspective, as if the Edison train films featured a phantasmal bullet train shooting past an oncoming dystopia; the Metal Fetishist’s iron palace in his apartment has a striking similarity to the wasteland of scrap in old industry buildings during the late battle sequences. Tsukamoto is equally concerned with a looming claustrophobic urban environment, such as the transformed Los Angeles of Blade Runner; he uses space and architecture to trap his characters, increasing the tension as they break through the doors and walls of their glinting iron universe. Tetsuo: The Iron Man‘s mingling of flesh and metal is rivaled only by its mingling of genre themes to a historic cult success.

2. Body Snatchers

Written by Stuart Gordon, Dennis Paoli, and Nicholas St. John

Directed by Abel Ferrara

USA, 1993

Abel Ferrara’s Body Snatchers is of course a remake of Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but can also be seen as a remake to Philip Kaufman’s remake of the original, which is also an adaptation of a book by Jack Finney. Hell, it isn’t even the last in line as Edgar Wright’s The World’s End can also be seen as a loose adaptation. Ferrara’s vision is the first one to shorten the title, but this continuation of a theme of extraterrestrial beings kidnapping human bodies — their lives being meaningless collateral — seems to interest each generation for different purported reasons. The original was attributed to the horror of McCarthyism, Kaufman’s version documents a culture switch in the 70s, and Roger Ebert speculates that Ferrara’s may have dealt with the AIDS crisis: regardless of time, the “body snatcher” mythos is a bit of a Rorschach opportunity.

Marti (Gabrielle Anwar) is brought along to an army base in Alabama with her father Steve (Terry Kinney), sent as an agent of the EPA to test environmental damage by military procedures. Her interior monologue reveals that the others in the car are part of her new family, including her stepmother Carol (Meg Tilly) whom she distrusts as well as her half-brother Andy (Reilly Murphy) whose childish innocence allows Marti to like him. Along the way, Marti is spooked by a conspiracy-speaking Major, already in tune to the idea that something is definitely wrong in the military base and is subsequently in hysterics; his delusional rantings are brought to fruition as Marti discovers that everyone in the camp and eventually her friends and loved ones have become inhabited by an emotionless, rigid society of “pod people,” dedicated only to spreading their infection to the rest of humanity.

Themes of loss of identity and culture-shifting have been portrayed in films before, but never with this mixture of visceral terror and genuine curiosity. Ferrara’s setting of the army base is ripe for political attention, as the behavior of snatchers directly aligns itself with our idea of militaristic sensibilities: situational order and structure is given primary attention while individuality and emotion are demonized as being a weakness to the system. The political side is related to the idea of the explicit loss of humanity that comes with these features: anything perfectly exhibiting these qualities is considered “off”, scaring both the Major and later the remaining cast of humans. Despite calling audience attention to these details by making us question which of Marti’s family still have their humanity (a focus on the eyes, a wonderful cinematic device used since Carl Theodor Dreyer), a mere political allegory would be too easy for Ferrara. Instead, he uses the high concept of the snatchers to bring Marti’s fears of her stepmother to be actualized in front of her. She already had feelings that Carol was not her “real” mother, rather she is merely a replacement, a stand-in that behaves differently than what she would associate with motherhood. By literally replacing the human mother with a replicated automaton (a high-concept action related only to the film’s sci-fi qualities), Marti’s horror is even more evident as its “otherness” is a brunt upon her psyche. The end of the film presents a Marti who revels in the destruction of the Others, her own humanity now removed without the need of alien infestation. Ferrara’s addition is one that truly understands for what purposes genre movies can be utilized, tackling our rooted personal and societal fears with a sense of wonder.

1. Alien

Written by Dan O’Bannon

Directed by Ridley Scott

USA and UK, 1979

From the atmospheric title sequence to the moment of live alien birth to the memorable set pieces, no sci-fi horror film could possibly be more iconic nor define the genre better than Alien. Ridley Scott stays close to our world while building his: the protagonists are not scatter-brained adventure-seekers, but economically minded engineers and specialists whose mining obligations are interrupted by signs of life, their scientific curiosity spelling their deaths. As Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) maneuvers around the ship with her crew in search of the intruder, she exhibits a level of professionalism in a haunted house scenario that takes away cries of verisimilitude problems other horror films may face. It is mainly due to Ripley’s resolve that the lone intruder has remained so historically terrifying: Weaver plays Ripley’s fear as that of a disgruntled problem-solver, one who first fears the creature as an obstacle, and later, in her escape pod, as one of transcendent terror working against her best judgments and scientific instruments. In stories of terror, we rely upon those with the guns, those with the know-how, and those with a commanding voice; yet, cosmic intruders do not know of our authority and will always circumvent it.

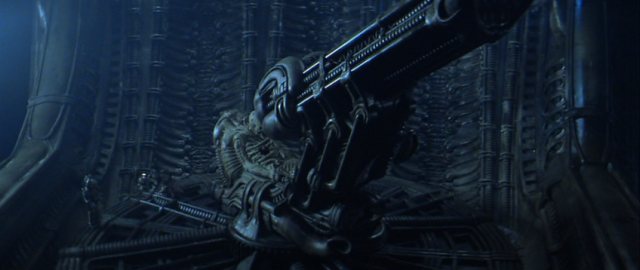

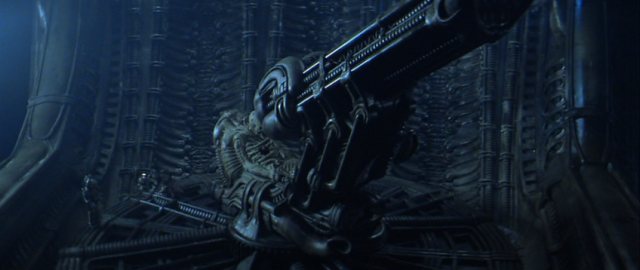

However, this is not to diminish Alien‘s more cinematic qualities of a horror-inducing minimalism that summons the atmosphere of another film that took science fiction seriously: 2001: A Space Odyssey. This was later replicated for a similar effect in the eerie Beyond the Black Rainbow. Long yet cramped hallways, limited lighting, a visual feel for the vastness of space, as well as a soft and saturated score by Jerry Goldsmith compose an atmosphere suited to hiding H. R. Giger’s surreal creature in the shadows, its presence always felt rather than seen. The atmospheric horror piece is the diegetic opposite of the jump-scare tactics commonly used by lesser filmmakers as an easy route to shock, but Alien nonchalantly utilizes both. After a series of echoed shouts, a crew member finally happens upon a lost cat: a simple discovery shot with static takes and moody, strobe-like lighting. His ultimate demise is foretold not by formal conventions, but by the cat’s interjecting hiss at the off-screen creature; cut to its cloaked reveal only to fixate on the cat’s deadpan face during the violent act, an odd choice for a film reportedly inspired by The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Other scenes reflect on the exchange between atmosphere and visceral shock, Ripley’s respite in the escape pod followed by her rediscovery of the alien’s survival being vital, yet its formalist qualities also sharply divide an audience’s claustrophobia and agoraphobia as it places us both in the R’lyeh-like planet of eggs as well as the narrow confines of the ship’s architecture. An intelligent, ever-morphous environment and atmosphere drive our befuddlement with the creature as we are unravel its mystique along with the crew, slowly coming to terms with its dominion over even the most intelligent horror victims.

Earlier this month, Edgar noted the fans’ split between crowning Alien and Cameron’s Aliens as the sterling representative of the franchise. Qualitative evaluations comparing both films remains a difficult task, as the movies are crafted by such different auteurs trying to use the world for different cinematic purposes; however, whereas Cameron plainly utilizes the Alien mythos as his setting for large-scale action, Alien is required to calmly build it as it goes, unwittingly setting the stage for Aliens. The additional “s” on the title is already terrifying for those who have seen Scott’s vision, as viewers have already experienced the terror of one; a plural meaning certain destruction. Surely the franchise rests upon Alien, the film singularly encapsulating the horror of the scientific unknown, and remaining a masterpiece of genre filmmaking.

-Zach Lewis