After more than 50 years since first shocking the film industry and audiences’ psychological inadequacies, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is still marveled as being the archetypal foundation for modern-day horror films, as well as the driving force behind today’s censorship standards. Since its release in 1960, Psycho’s mass appeal undoubtedly comes from its atypical iconic elements. From drawing sympathy toward evil, creating violence with the lack of imagery, and using the camera to manipulate the audience’s point of view, Psycho has unquestionably marked itself as an influential, timeless classic in the eyes of both filmmakers and fans alike.

Perhaps noted as the most famous scene in cinematic history, the 45-second shower scene encapsulates all the brilliant elements that make this film a masterpiece. After spending a third of the film with Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane, in a short, electrifyingly brutal scene, the film switches to Bates’ point of view and the audience is invited to sympathize with his psychotic dilemma over confronting his mother’s fatal crime. This effect to play with the audience’s sympathy was never vastly dealt with in mainstream filmmaking before. Not only was it pioneering, but it was the foundation to what would become the “slasher” sub-genre. As many horror films during the time were presented in the third person, Hitchcock’s use of first-person shooting between victim and killer maneuvers the audience to exactly where the suspense occurs. Thus, the audience identifies with the crisis, intensifying the horror more so than displayed on screen. If it wasn’t for this unforgettable scene, we wouldn’t have the slow-motion violence of Bonnie and Clyde in the later part of the 1960s, nor would we have evolved slasher films like Halloween in the 1970s and the Saw films of today.

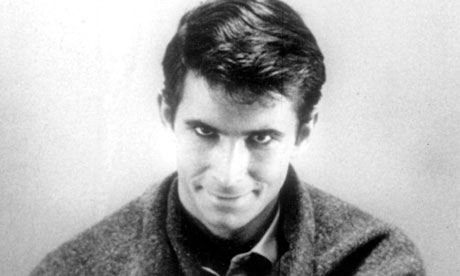

Through the film’s digression, we can see how Psycho represents a benchmark for many of today’s modern slasher hits. Norman Bates is the original killer, characterized as the psychotic product of a sick family, but still recognizable as a human. This is the basis for films such as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The Bates Motel is the locale of the killer’s horrific origins, akin to Michael Meyer’s asylum in Halloween. The knife is his weapon of choice (similar to the killer in Wes Craven’s Scream), and the helpless woman is the first victim to go or last person to stare death in the face (modeled after Marion Crane). With this, the legacy of Psycho is most apparent in John Carpenter’s Halloween, threaded by its transgression of the barrier between psychological and supernatural monster, becoming the prototype for many late-1970s and early-1980s slasher hits such as Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street.

One can surely go on about the vast influence of Psycho and Alfred Hitchcock’s ingenuity on the horror genre in general, but to do so would only make the point sound repetitive. Psycho was and is so ahead of its time, so detailed, so risqué in more ways than one, that by not including it in the pantheon of greatest films ever made would make any other choice irreverent and irrelevant.

— Christopher Clemente