The Merc with the Mouth is infamous for two (often overlapping) categories of crazed conversation: 1) comedic quips similar to Spider-man’s, sans a profanity filter, perhaps slightly more emphatic on non-sequiturs and random ramblings, and 2) fourth wall shattering soliloquies to the reader. For many, the concept of a character cognizant of being in a comic book is their first experience with metafiction in the medium. Such goes beyond self-awareness, of course, and many of the greatest graphic novels and individual issues are comics about comic books in one way or another.

Oftentimes, Deadpool’s own breaks with the fourth wall are played for laughs, evidence more of a break with his own reality than any breakthrough to the reader’s. While this approach is absolutely appropriate for the ever droll Deadpool, writers on other title have employed the same device for the purposes of profundity, a means of making metafictional musings into metaphysical ones. They are calls for contemplation not merely on the relationship between the reader and the text, but on ontology and the ultimate nature of reality. After all, if the physical world is a step above the fictional, by analogy, what’s above the physical?

This isn’t the idle, drug-induced ponderings of first year philosophy students. Comics’ other Big Two, Morrison and Moore (okay, so there were definitely drugs involved), both have highly systematized schools of thought which integrate imaginative fictions into their roadmap of reality, as seen most clearly in Supergods and Promethea, respectively.

While by no means a comprehensive enumeration of every instance such has occurred (for that, TVTropes has an exhaustive entry), nor even the best or most important per se, the following are a few fourth wall breaking comics fans of Deadpool should check out.

* * *

Any examination of the fourth wall in comics needs to begin with the notion of Earth-Prime, the DC Comics designation for the real world of the reader, as it is purportedly the vast outdoors that lies on this side of the wall. “Purportedly,” because in its initial appearances, Earth-Prime was clearly as fictitious as the so call Earth-One, Earth-Two, and infinitely others more. After all, it is quite clear that this world has never been visited by The Flash, an alien refugee named Ultraa, nor did it give rise to Superboy-Prime, and obviously it wasn’t destroyed in a multiversal cataclysm (that definitely would have made the evening news). In fact, Psycho Pirate’s address to the reader in the final panels of Crisis on Infinite Earths #12 indicate that the real world was not Earth-Prime, nor even nominally part of the DC multiverse (then reduced to a single universe), but nevertheless accounted for in a larger cosmology.

Twenty years hence, however, writer Geoff Johns began to play with the notion of Earth-Prime really being just Earth, the existence of which certain characters were aware. In issue #6 of Infinite Crisis, while searching the multiverse, Alexander Luther inquires aloud, “Earth-Prime… where are…? You.” In uttering the second persona pronoun, Luther looks directly through the panel, meeting the reader eye to eye, implying Earth-Prime to be this side of the fourth wall. The very next panel his gaze remains fixed upon the reader, his hands outstretched as if reaching through the very page itself.

Johns would later revisit the issue in the famous finale of Final Crisis: Legion of Three Worlds. Despite his defeat as the series’ antagonist, Superboy-Prime returns to the restored Earth-Prime, per his goal all along. Yet this being the Earth in which DC Comics publishes his adventures, immediately upon arriving at his parents’ home they hold up a copy of Final Crisis: Legion of Three Worlds #5, disappointment plastered on their faces, saying, “We know exactly what you’ve done.” In the final page, Clark is seen reading the final page, turning to the reader.

“I’ve been waiting for this stupid thing to end. Hey, don’t think I don’t think you’re thinking the same thing! Because I know you’re out there! Stop staring at me!” At this point, Clark throws the floppy in a fit of rage. “You go away! Get out of here!”

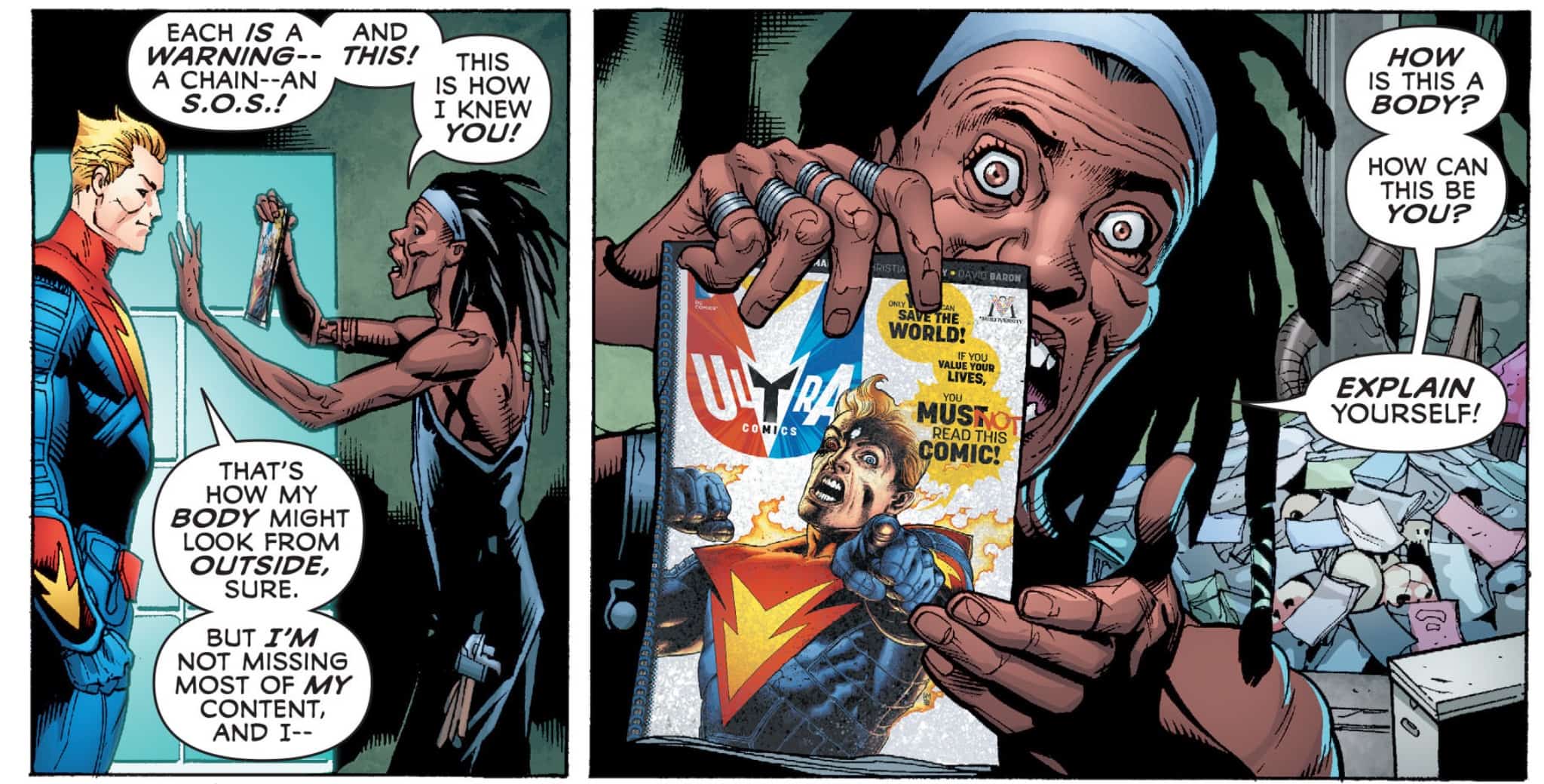

Once again, a confusing conflation of Earth-Prime and the real Earth was being presented, but that would soon be clarified after the next continuity wide reboot, Flashpoint. Of the “New 52” universes that emerged, the one designated Earth-33 was named also Earth-Prime. However, this is no pseudo real-world, no near facsimile; it is Earth, plain and simple. As such, it is home to one superhero only, Ultra Comics #1, part of Grant Morrison’s magnum opus The Multiversity. In its own words:

“Not a hoax! Not a dream! Not an imaginary story! Not an elseworlds tale!”

How can this be? The name of the character is the signature tell here: Ultra Comics. That is to say, the character is not the blond-haired humanoid seen throughout the comic, but the very comic itself, the one the reader holds in his hands as he reads it. Page seven says it all:

“My body, made from pure cellulose pulp, salt water and carbon. Titanium dioxide, wax emulsion, formaldehyde. My skin of water glycol, iron blue, azo pigments. The staples of my spine!”

There’s rarely a panel the Ultra is not looking directly at the reader, never a thought bubble or narration box not intended as a soliloquy to the audience offstage.

By while Ultra Comics was itself the logical conclusion to the idea of breaking the forth wall, utterly shattering it by creating a comic book character that existed only and entirely in the real world, it was a previous issue of The Multiversity that gave insight into Morrison’s career-spanning fascination with the relation between metefiction and metaphysics in sequential art. In Pax Americana #1, Captain Atom (the Charlton Comics character which inspired Dr. Manhattan) is seen reading Ultra Comics. Pondering aloud as he reads, he states (seemingly to two scientists working on the particle accelerator in which Atom is holed up):

“Complete and yet always beginning and ending. Always different. The story’s linear, but I can flip through the pages in any order, any direction. Forward in time to the conclusion. Back to the beginning. The characters remain unaware of my scrutiny, but their thoughts are transparent, weightless in little clouds. This is how a 2-dimensional continuum looks to you.”

The, staring straight ahead, surely no longer speaking to the scientists, or at least not only to them, he concludes, “Imagine how your 3-D world looks to me.”

Such alludes to how many metaphysicians interpret the equations of quantum physics regarding the nature of space and time. In J.M.E. McTaggart’s B-theory of Time, there is no objective present moment. All events, from the Big Bang to the Heat Death of the Universe, exist simultaneous to one another as a 4-dimiensional manifold known as Minkowski spacetime. From an observer at any point on that manifold, he would regard some other points as “earlier” or “later” than his own, but they would not be objectively past or future. Morrison’s point here is that the format of a comic book serves as an appropriate analogy for a more accurate understanding of reality than humans naturally intuit. It may very well be that all men are, in a very real sense, characters in a comic book which is already written, heroes of a story already set down.

Morrison himself claims to have seen the cover of the comic that is the universe, to have flipped through its pages after achieving enlightenment at the Shwayambunath temple in Kathmandu. After ascending to a heavenly hyperspace accompanied by alien angels, Morrison recalls:

“There was time and there was space, but those were lower dimensions, useful for creating worlds in the same way that comic book artists drew living worlds on paper. Here was an unending perfect day of absorbing eternal creation… Some of what they tried to show me was simply too fantastic, too reliant on higher dimensional topographies for a 3-D mind to contain… Television talks of a ‘fourth wall’ of the set as being the screen itself. If so, this was a glimpse beyond the fifth wall of our shared reality. Five-dimensional intelligences could, as a condition of their geometrically elevated position, get into our skulls quite easily, and we could expect their voices to come from inside. They, in turn, could hear our thoughts as easily as we can read Batman’s private inner monologues on a 2-D page.” (Supergods, p. 273, 277)

Morrison’s claims clearly go beyond the equations of Minkowski or the speculation of McTaggert. His concern is not merely the shape of reality, but its purpose as well. If the universe is a cosmic comic book, who are its creators; who writes the plot lines of history, pencils the particle interactions, letters the thought balloons of intelligent minds?

It is the other leader of the British Invasion that offers the most interesting answer to such inquires. In Promethea #15, Alan Moore has the titular science-heroine travel to the celestial sphere of Hod where she meets Hermes himself. Trismegistus tells her, “It’s all a story, isn’t it? It’s all fiction, all language.”

Sophie objects.

“But this isn’t fiction. This is our real life.”

“Ha! Real life. Now there’s a fiction for you… To perceive form, even the shape or form of your own lives, you must dress it in language. Language is the stuff of form.”

“So everything’s made of language? We’re made of language? Even you?”

“Oh, especially me! How could humans perceive gods – abstract essences – without clothing them in imagery, stories, pictures – or picture-stories for that matter.”

“Picture-stories?”

“Oh, you know, hieroglyphics, vase paintings. Whatever did you think I meant? Besides, what could be more appropriate for a language-god to manifest through than the original pictographic form of language?

“So what are you saying?”

“I’m saying that some fictions might have a real god hiding beneath the surface of the page. I’m saying that some fictions might be alive – that’s what I’m saying.”

It is at this point that J.H. Williams’ interpretive icon of Mercury is illustrated as breaking the forth wall, speaking directly to the reader, yet from the context it is evident that Moore’s higher aspiration here was for the “god” himself to through such soothsaying break the fifth wall. To be clear, Moore is not arguing that the specific pagan deity which in mythologies has been called Hermes, Thoth, Wotan, and other names exists. But part of his thesis behind Promethea is that the physical world is no more real (indeed, less so) than the meaning and ideas behind it. That there is real truth, real meaning, behind the cosmic comic book.

When Hermes says, “Some fictions might have a god hiding beneath the surface of that page,” Moore is not merely indicating his own work to be inspired; rather, it is in the context of Hermes saying, “Real life. Now there’s a fiction for you.” By Moore’s account, real life is a cosmic comic with higher truth and deeper meaning behind what is seen. Such is no pretentious platitude, but a very serious proposal for an architectonic structure to reality. As such, picture-stories such as comic books and graphic novels are particularly well suited to conveying those truths, more so than most any other medium.

* * *

The occasion for this article is of course the impending release of Deadpool in theaters. Where once superheroes and comic books were inseparable from one another, the genre has found a groundswell of popularity which the medium has never known. Fandom initially found a great deal of validation with each new adaptation of a beloved property, but on the eve of Marvel’s Wave Three and a full-fledged DCWverse, that initial infatuation with screens silver and small seems misplaced. It was not only the characters which were long loved, but the form in which their tales were told.

Instead of always translating the page to screen, treating comics as mere story-boards for films, making the strange and fantastic more palpable to the general populace, perhaps in the inevitable post-superhero movie crash comic fans should become more insistent in being met where they’re already at. What if everyone who buys a ticket to Civil War were to instead read Ed Brubaker’s run on Captain America? What if everyone who sees Batman v. Superman were picking up Scott Snyder’s series’ monthly?

After all, as their varied breaks of the fourth wall demonstrate, comics are uniquely and especially imaginative medium. Comics are the medium whose structure most closely mirrors reality itself at the highest physical and metaphysical levels, and as such are the medium most suited to convey its highest truths and deepest meanings. Comics at their best are a religious experience, a path to enlightenment through penciled pictures on pulp paper. These are stories with a real god hiding beneath the surface of the page; these are stories that are alive. Let’s work to keep it that way.