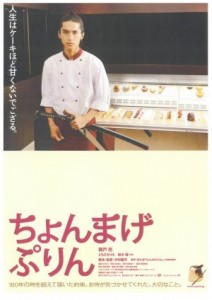

Written and directed by Yoshihiro Nakamura

Japan, 2010

Yoshihiro Nakamura’s fish-out-of-water comedy, based on a manga, concerns an Edo period samurai thrust forward in time to contemporary Tokyo and befriended by a single mother and her young son. Instead of a narrative rooted in the action film genre like one may expect from the man’s profession, the film’s concern is with the subversion of the samurai mindset and cutesy familial development. The samurai, Kajima, ends up stepping into a modern domestic role as a surrogate father and housekeeper, becoming a master of domestic duties. Discovering and developing a fondness for sweet food, he begins to hone skills in the art of pastry-making through the application of the same principles and dedication related to samurai training. This development alternately brings this new family dynamic closer together but also threatens to tear it apart.

As is the case with many time travel comedies, the highlights of A Boy and His Samurai’s humour stem from conflicting sets of values and technological acclimation. One short highlight is Kajima’s first encounter with a ringing phone when left home alone; assuming the sound to be that of a demon, he brandishes his sword for battle. Despite this incident, he is otherwise portrayed as a smart man, which is a refreshing approach. The character’s frequent commands for obedience also serve as a successful running gag. In regards to conflicting values, the film has Kajima struggling with the notion of Yusa, the mother, being a career woman and not defined by any relationship to a man, exploiting the inherent humour of outdated sexual politics via Kajima fulfilling the role he has always associated with women.

A Boy and His Samurai is, for the most part, a very enjoyable and surprisingly low-key family film, its sweetness and cute whimsy never cloying. Where it perhaps suffers somewhat is in its leisurely approach. Consistently charming for its first half, the film begins to feel a bit lost through a lack of any strong conflict, excluding Kajima suddenly being unable to remain a constant daytime presence in the household due to an employment opportunity of his own. The latter half of the film relinquishes many of the comedy trappings, and some of its forays into dramatic territory don’t feel entirely satisfying. A key scene towards the end of the film also sees a band of thugs suddenly being introduced, forced into the narrative as a physical threat in a film that has had none. Sparring with Kajima in the street in front of a crowd, the dramatic confrontation poses no consequences and feels like an excuse to have the samurai display at least one demonstration of his fighting prowess before the film ends, adding to an increasingly drawn out feeling runtime.

Bar complaints about some arguable superfluous elements, A Boy and His Samurai is an enjoyably sincere effort free of an annoying brand of irony prominent in many contemporary family films. Anchored by strong lead turns, it contains a potent brand of sweetness and some charming interactions; a samurai playing a game of Pokémon cards with a six year old boy is an unusual source of delight, but it is one nonetheless.

Josh Slater-Williams

This screened as part of the Glasgow Youth Film Festival, directly preceding the main Glasgow Film Festival which begins on February 16th.

Visit the official website of the Glasgow Film Festival.