The beauty of art is that you can have a nearly out-of-body experience while watching it, listening to it, reading it, and so on. The mediums of art don’t always achieve this, but whether it’s a painting, song, book, poem, television show, or film, we can be both fully transported into another world while also being aware of the effect the art is having on us in the moment. You’ve had this happen when you saw a certain film, read a certain book, heard a certain song. It happens to all of us, even if we’re not fully conscious of it in the present. But when it does happen, and we know it’s happening, this experience is something to treasure. Most, though not all, of the films from Pixar Animation Studios feature such powerful, moving, singular moments, chief among them the dancing sequence in WALL-E.

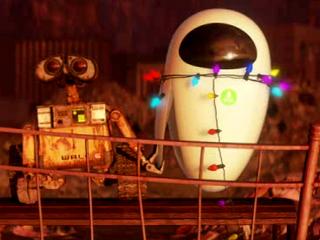

What works so well about the films from Pixar is that the moment I take away most from WALL-E, the moment I treasure so much, may not be the moment you take away. You may acknowledge that, sure, the scene with WALL-E and Eve dancing around the Axiom, a cruise liner in space, is sweet. But it’s not the scene for you. No, you like the first 30 minutes of the film, or the first scene with WALL-E rolling around the trash-filled planet once known as Earth. But that’s OK. We each walk away from a great film with something different. None of us are going to think there’s only one so-called “Pixar moment” (I’m copyrighting that term, so don’t even try) in each of their films.

That’s why Pixar films are so special. Like other great works of art, they work for different people in different ways, even if we all—or most of us—agree that their output is almost uniformly excellent. We bring our experiences, our hopes, our fears, our dreams, and more to each Pixar film. Though you could argue that such a mentality isn’t unique to Pixar, I think it’s a bit different because Pixar is our generation’s version of Disney. People of a certain age or older (in this case, the baseline is roughly 20 years old) may remember when their childhoods were shaped specifically by Disney animated films like The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, as well as older films such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. But those people have grown up with Pixar dominating in the world of animation.

Because of that, a movie like WALL-E comes with great expectations. From the studio that brought us classics that defined our childhoods, we expect nothing less than the best. That director and co-writer Andrew Stanton is able to deliver something awfully close to perfection is truly jaw-dropping and impressive. The premise, of finding love and companionship in a dystopian future, isn’t enormously ambitious or groundbreaking, but the execution makes the film stand apart.

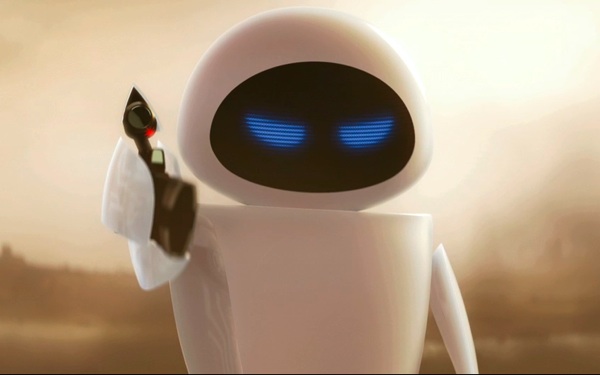

Our title character is a robot who doesn’t speak English, aside from saying its name in a mechanical chirp. It (though as our guest Rowan Kaiser mentioned, the coding on the character is clearly meant to be masculine, so I’ll refer to WALL-E as “he”) works on Earth alone. All other WALL-E models have broken down, so only our WALL-E is working on compacting trash for removal by machines that will, now, never come. One day, a massive ship descends upon his part of the world, dropping off a sleek white probe named Eve, whose job is to look for signs of sustainable life in the hopes that mankind can return to its former home. WALL-E falls hard for Eve, partly because he’s been so desperately alone for so long, and partly because she charms him with her sometimes-sweet, sometimes-rigid personality. She eventually falls for him, of course, but not immediately. What does happen almost instantly is that WALL-E shows Eve the plant he found, inexplicably living in an old shoe. This sends her into hibernation, back onto the ship from whence she came, and it takes WALL-E on an adventure into the future of humanity.

The second half of the film is a bit more conventional in its storytelling style than the first half—well, that’s an understatement. The second half of WALL-E is a rousing, entertaining short film, but seems weirdly attached to the first 30 to 40 minutes, which is a poetic, moving, and beautiful piece of animation. Watching WALL-E traverse around the heaps of garbage on our planet shouldn’t be so powerful or awe-inspiring to watch, but Stanton and the animators at Pixar do such an excellent job of finding the wonder and magic in such a desolate, dystopic place. Though there’s no question this film falls with any other dystopian entry in the genre, the buoyant positivity and upbeat nature of WALL-E makes it stand apart. There are extreme changes to the world of the future, but Stanton never wallows in the changes, letting the title character’s optimism radiate so much we’re beaming with him.

Some of the changes are, perhaps, too extreme but even in the most obvious case, I’m not sure what Stanton could’ve done to fix the problem. We find out halfway through the film that the rest of mankind not only lives on a massive cruise ship in space, but are all ridiculously obese, to the point where they can’t walk (or don’t walk, at least). Their bones and muscles have atrophied, making them cartoonish blobs. Though the depiction of humans in Pixar films has progressed from seeming too fake, almost employing the “uncanny valley” effect so well-recognized from Robert Zemeckis’ latest movies, to being believable yet not completely outrageous, here, it serves a point. I’m just not sure that the point could ever be made without feeling distracting.

The whole point of us seeing humans in the 2800s is to, in some ways, jeer at how they’ve devolved from where we are now. Of course, it’s as much a message to us to stop trashing our planet and being lazy; instead, we need to work harder and not make technology serve us so much that we don’t get anything done. The problem with how this point comes across is built into the story. The first half of the film manages to feel photorealistic in its style, and even though WALL-E and Eve don’t look completely like you could touch them, they’re awfully close. What’s most notable is that there are no humans in the first half of the film, outside of the comic actor Fred Willard, playing an actual, live-action human being.

So when we first meet the humans on the Axiom, it’s nearly a whiplash-inducing moment. I’ve seen WALL-E many, many times by now, and it’s still a bit distracting. I know the overweight humans are coming, I prepare myself, but I can’t get over how strange they look compared to not only what I expect humans to look like, but to the rest of the environment and characters. I still care about their struggle, thanks mostly to a fine voice performance by comedian Jeff Garlin as the goofy and hapless captain of the Axiom, but there’s a slight lack of connection because of the stylistic choices Stanton and his animating team make in bringing humanity to life in such a purposely gross manner.

But these are nitpicks in a film that has touched me each time I’ve seen it. The moment where WALL-E and Eve dance in the space around the Axiom, spinning and swirling next to each other in perfect synchronization, giddy at the possibilities in front of them, is magic. Each film from Walt Disney Pictures—hell, most movies in general—try very hard (or should try) to create magic. Most of the films we’ve talked about on the podcast haven’t come that close for me. Every time I watch WALL-E, I am bowled over and impressed by how Andrew Stanton, sound designer Ben Burtt, composer Thomas Newman, and every single animator on the project came together to create the pure wonder of this scene and this film as a whole. Few people will make movies as singular and brilliant as WALL-E, so we should consider ourselves lucky that it even exists.