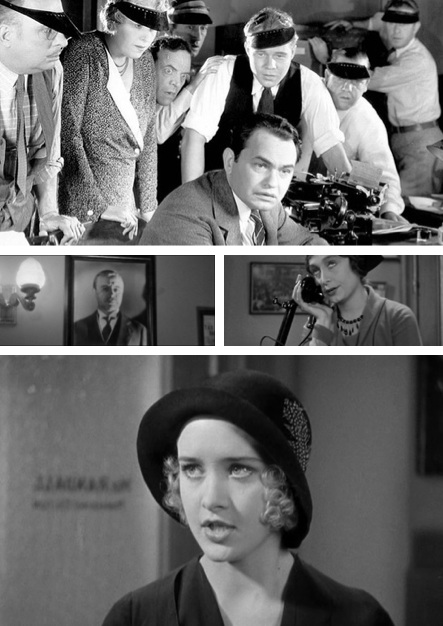

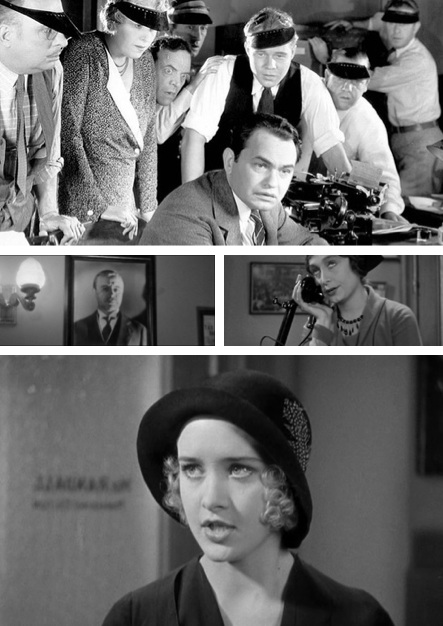

“Now you listen to me, Hinchecliffe. It’ll be for the last time. I’m through with your dirty rag, and I’m through with you. Oh, I’m not ducking any of the blame for this thing. You thought of the murder and I committed it. But I did it for smaller profit. For wages. You did it for circulation.” — Randall, as played by the brilliant Edward G. Robinson

I’ve written about LeRoy’s work before, a director quickly becoming a favorite of his era, but that was a comedy, albeit one with sharp teeth and tragic implications. Five Star Final is unbearably tense melodrama more in the vein of the also exceptional Two Seconds. Superficially concerned with the actions of a newspaper and its working parts as they dig up an old murder story to rejuvenate circulation numbers, like Hard to Handle, it winds up being a film far ahead of its time. LeRoy is a champion of the working class, and as this working class are most vulnerable to disinformation and higher society narratives, Five Star Final fits snugly into LeRoy’s filmography sympathetic to his pet cause.

LeRoy begins his excursion into feminist themes quickly by framing some female operators behind a veritable cobweb of wires, trapped in a small room and given the task of transferring calls to the men who field them. Their voices drained of contrived perkiness, they seem annoyed at every new phone call. Randall is the managing editor of the editorial section, and word comes in that circulation numbers are dropping and his love stories aren’t pulling in the audience they used to. The idea to resurrect a twenty year old murder story is proposed, a story explicating the real life murder of a husband by a wife. Crucially, the circumstances surrounding the murder are kept from the audience, but the woman was let go due to her pregnancy. The newspaper seeks to rip open old wounds and upend the idyllic foundation of a new family on the back of this woman, whose action may very well have been justified. In order to help with the investigation, Randall hires a busty reporter to replace a smaller-chested woman. She’s to be dangled in front of leads for additional information. A friend of Randall’s, a notorious womanizer, wears his lack of journalistic ethics like a badge of honor. The murderess’ daughter and soon-to-be husband playfully mock gender roles and generalizations as they prepare for their wedding, a touching and hopeful gesture toward the future.

It’s in the final third or so of the film where the fury really breaks loose and the trenchant melodrama strikes like lightning and churns your stomach. Maintaining a constant level of tension and inducing righteous disgust, the murderess’ daughter becomes LeRoy’s enraged mouthpiece, shouting the rhetorical question of why these people killed her mother and the contentment they so enjoyed before their muckraking tabloid paper resurrected a story best left in the past. Again, themes of working class angst and an inability to escape one’s past penetrate the picture and tie the film closely to its Great Depression timeline. Since it seems LeRoy was at the peak of his prolificity in and around the Great Depression, I’ll be continuing to dig in there for hidden treasures of his.

– Chris Clark