One of the most talked about films at this year’s Sundance Film Festival is Randy Moore’s Escape From Tomorrow. To shoot his film, set in Disney World, Moore purchased a season pass to the park and secretly filmed his actors without the park’s knowledge. There is no question that, at a minimum, Moore violated the terms of entry on the tickets he purchased. It’s possible that he could be prosecuted for trespass. The larger question though: Does the film violate Disney’s copyright? Or to put it in a way that film fans actually care about: Will the film ever be released? Will we ever be able to watch it?

The New York Times suggests that Moore will have problems releasing the film, “The movie, while careful to leave out certain copyrighted material (like the “It’s a Small World” song), would seem to test the limits of fair use in copyright law.” The New Yorker, on the other hand, suggests that Moore would ultimately win in court, “As commentary on the social ideals of Disney World, it seems to clearly fall within a well-recognized category of fair use, and therefore probably will not be stopped by a court using copyright or trademark laws.”

On the gripping hand, it doesn’t matter whether Moore would win in court or not. While he may have had the resources to film his movie (using an inheritance from his grandparents to do so) it is doubtful that Moore has the resources to fight the trained pit bulls that Disney employs as lawyers. At a minimum, the Walt Disney Corporation could probably delay a wide release of Escape From Tomorrow for years, and there is no guarantee that Moore would win in court.

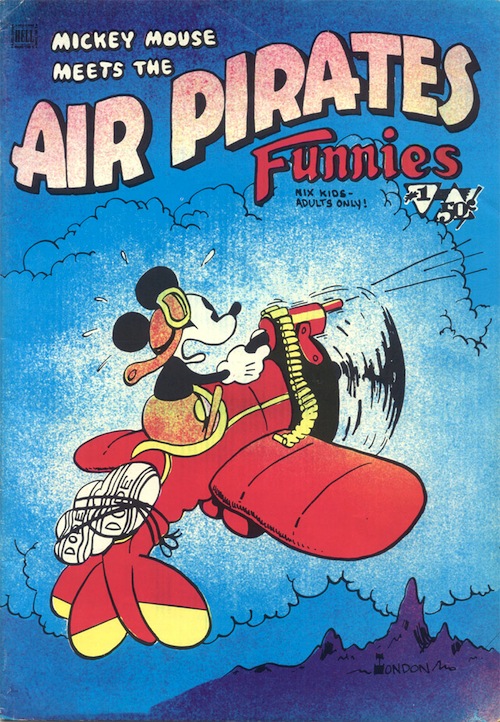

This leaves the Walt Disney Company with a dilemma, one that they have faced before – in an eight year legal battle called: Walt Disney V. The Air Pirates. In 1971, a group of underground cartoonists led by Dan O’Neill published a comic book (or, more properly, a comix book) called Air Pirate Funnies. Two issues were published, with a print run somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000 copies. Each issue was filled with Disney characters swearing, having sex, doing drugs and generally behaving in ways designed to make any Disney executive blow their tops. That was the entire plan. The cartoonists got the son of a Disney executive to sneak copies of the two books into a Disney board meeting and they promptly got sued for copyright infringement, trademark infringement, unfair competition and anything else that the Disney lawyers could dream up.

The truly odd thing about The Air Pirates case is that one of O’Neill’s motives for getting sued for violating copyright was to get back his own copyright on the cartoon Odd Bodkins that he drew for The San Francisco Chronicle. O’Neill believed that since he had previously used Mickey Mouse in those strips for (much tamer) satirical purposes, that if he was sued by Walt Disney, the Chronicle would give him back the copyright so as not to be dragged into the legal quagmire. (And in fact, in 1972, the Chronicle did transfer the copyright of Odd Bodkins back to O’Neill.)

The legal defence of Air Pirate Funnies was the same that The New Yorker suggests for Escape to Tomorrow, the “well-recognized category of fair use“. The traditional narrative of these types of stories is that of the plucky artist, fighting against the monolith, winning legal battle after legal battle, but in danger of losing the war because of the greater resources of his corporate opponent. That is not what happened at all. AT ALL.

The Air Pirates lost every single case and every single appeal. Some argue that The Air Pirates had a winnable case, except that they kept antagonizing their judges by acting like the counterculture cartoonists and weirdos that they were and by doing things like releasing more Disney parodies when the court had explicitly told them to stop. Or raising money for their legal defence by selling even more Disney parodies. “Doing something stupid once,” said O’Neill, “is just plain stupid. Doing something stupid twice is a philosophy.”

But losing was O’Neill’s strategy. He reasoned that if forced the Walt Disney Corporation into a choice between sending him to jail for drawing Disney parodies or giving up the lawsuit, that they would give up the lawsuit. After eight years and (reportedly) two million dollars in legal fees, Disney settled with O’Neill and Ted Richards (the only remaining Air Pirate still being sued), dropping the lawsuit in return for an agreement to stop infringing on Disney’s copyrights. Ironically, or perhaps predictably, O’Neill later sued Walt Disney for violating his copyright, alleging that the character Roger Rabbit was based on his drug-dealing rabbit Roger from The Tortoise and the Hare.

The end result of the lawsuit is that a comix book that had a print run of, at most, 20, 000 books was known around the world and issues of Air Pirate Funnies are both hard to find and highly collectible. All Disney succeeded in doing by trying to suppress Air Pirate Funnies was make them famous.

Except that is not the way that the story is remembered… It may be the facts, but it’s not the legend.

Amongst comic book and science fiction fans who don’t know or don’t remember the full history of Walt Disney V. The Air Pirates, this story gets conflated with an equally famous story about how Harlan Ellison was fired by the Walt Disney Corporation, after working there for a grand total of four hours! Ellison was fired after making a joke pitch – about an animated Mickey Mouse porno – during lunch, while seated in the Disney commissary near Roy Disney. While young artists may not know the full story of either Ellison’s firing or the Air Pirates lawsuit, any time that someone draws a salacious picture of a Disney character – especially if it is Mickey Mouse, the moral of Ellison’s story is repeated, frequently while said drawing is being hastily destroyed, “Big business is humorless. And . . . At Disney, nobody fucks with The Mouse.” Or just “nobody fucks with The Mouse.”

This also gets conflated with the fact that the time limit for copyright keeps getting moved, largely to protect Mickey Mouse. Amongst filmmakers, the first Mickey Mouse short 1928’s Steamboat Willie is used as a kind of copyright shorthand. If a film, book, piece of music was released before Steamboat Willie, odds are that it is not protected by copyright, and if it was released after Steamboat Willie odds are that it is still protected by copyright. The end result is an aura of fear that surrounds the Walt Disney Corporation and its copyrights.

This, then, is the Walt Disney Corporation dilemma. To protect their copyrights, they must “vigorously defend” them. They also don’t want to encourage other copycat filmmakers to follow Randy Moore’s lead and flood Disney theme parks with concealed cameras, perhaps doing stupid stunts for those cameras, endangering themselves and other innocent guests. And they have a reputation to protect as copyright bullies who will pursue cases of infringement for years.

On the other hand, Disney is well aware that trying to suppress Escape From Tomorrow would only draw attention to the film and increase its potential audience. As it is, just the fact that the Walt Disney Corporation might release its legal piranhas is driving much of the interest in the film. Taking active steps against the film could result in a public relations disaster and achieve the completely opposite effect, giving Randy Moore millions of dollars of free publicity and making his film a cause célèbre, another example of the Streisand Effect.

There is one potential solution to this Gordian Knot. One that would maintain Disney’s aura of invincibility, make Disney money and allow curious film (and Disney) fans to watch the film. The Walt Disney Corporation should buy Escape From Tomorrow. If Disney entered the bidding, most other companies would exit stage left, especially if Disney made noises about legal action to block the film’s release if they weren’t allowed to buy it.

The film itself is reportedly a dark satire of “The Happiest Place on Earth” ethos of the Disney resorts, with one of the characters in the film saying near the end, “You can’t be happy all the time. It’s just not possible.” (Fear not Mousterpiece Cinema Podcast listeners, I do know that “The Happiest Place on Earth” is the motto for Disneyland not Disney World.) One can see why Disney might be leery of that message about their resort being seen, but if the film is released by Disney, if Disney is in on the joke, it immediately lessens the sting of the satire. There is also an argument to be made that distributing a dystopian black and white reflection of the theme parks might only make the real parks look that much more colourful. And since the potential audience for the film includes every adult who loves Disney and every adult who hates Disney, the potential money to be made is almost incalculable.

But if Disney really doesn’t want anyone to see the film, they have the perfect in-house strategy to achieve that. Just hand the film over to the John Carter marketing team. The film will open in 3,000 theatres and no one will see it.