Written by John Hodge and Joe Ahearne

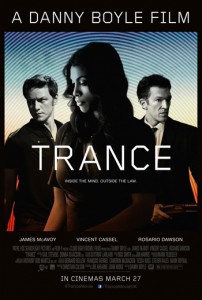

Directed by Danny Boyle

UK, 2013

Danny Boyle’s return to the thriller genre is also a return to the three character piece nature of his debut feature Shallow Grave, albeit placed within the confines of a heist film set mostly within the human mind. This is bound to draw comparisons with Christopher Nolan’s Inception, though Boyle’s film is actually based on an earlier TV feature from 2001, but Trance is a smaller beast scale-wise; a psychological thriller imbued with noir characteristics.

The psyche explored in Boyle’s film is that of London-based art auctioneer Simon (James McAvoy) who helps mobster Frank (Vincent Cassel) orchestrate the theft of a hugely valuable painting, only to provoke one slip-up during the heist’s execution that causes aspects of his memory to be erased, specifically the location of the painting which he himself has slipped out from under Frank’s thieving fingers. When graphic torture of Simon doesn’t work, Frank directs him to hypnotherapist Elizabeth (Rosario Dawson) so that she can uncover the location of a missing, desired object from the intricacies of Simon’s mind. This entire idea of Frank’s seems like it would only happen for the sake of making a high-concept film, but then most of Trance ends up far more concerned with its own structure than with its characters acting like plausible humans. Elizabeth, a most explicitly played femme fatale, works out that the painting is what Simon and Frank seek, and wants in on the haul.

Trance marks a reunion between Boyle and former regular collaborator John Hodge, who wrote all of the director’s films prior to 28 Days Later. As previously alluded to, their debut collaboration Shallow Grave was similarly concerned with three frequently contemptible individuals clashing over a MacGuffin of considerable monetary worth. The central difference between the two films’ narratives, beyond Trance’s plays with reality, is that Shallow Grave has a compelling moral dilemma at its centre that makes the drama interesting to see through to the end. This is a key attribute that Trance lacks, alongside the earlier film’s far more rounded characters. One of Trance’s admitted appeals is how extremely its power dynamics shift, with all three central players ending up as effective protagonists or antagonists at various points in the narrative, but by the film’s end the hollowness of this approach becomes evident.

The characters are ultimately one-dimensional ciphers there to be morphed by the narrative trickery and nothing more. One of them, Rosario Dawson’s Elizabeth, is also subject to some rather troubling gender politics and a truly baffling plot diversion related to pubic grooming. In a recent interview for Sight & Sound, Boyle suggested that “all the dark stuff we couldn’t put into the Olympics has ended up in Trance”. The pubic hair tangent, as well as the extremities in the depiction of the film’s violence and Trance’s general excess, feels immature more than anything; like what a horny, straight teenage male might conceive and call a dark and gritty mind-fuck.

The excess extends to the film’s style. The score by Rick Smith, a member of Underworld whom Boyle has frequently worked with, blares repetitively and acts as an omnipresent force from the offset, forever trying to create tension that rarely feels sincere. Part of why Trance never feels like it has any weight to its conflict is that the film is never at all grounded before it dives into the mind games. One such example is the film opening with Simon delivering a smug monologue straight to the camera, a stylistic trick never employed again after that point.

Anthony Dod Mantle’s cinematography has some highlights in its stark use of primary colours, occasionally reminiscent of his recent work on Dredd, but so much of the film is made up of super-saturated shots, edited together within an inch of life, at wild angles that bear little relation to the content or form of each scene’s context. Trance may well have as many or even more illogical Dutch angles than Tom Hooper’s latest, the only advantage being that the colours are at least a little nicer. The film is overtly showy and incessantly restless from its very beginning, the result being that the oppressive aesthetic drowns out engagement with the content. The process of watching the film still has some superficial pleasures, but they are just that. Upon reflection, Trance’s methods of hypnotising the viewer are very shallow.

Josh Slater-Williams