The Long Goodbye

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Leigh Brackett

USA, 1973

My introduction to classic film was through Humphrey Bogart. I would watch Casablanca (1942) and To Have and Have Not (1944) with my mother, but none of his films had as much of an effect on me as The Big Sleep (1946) and Bogart’s character, Philip Marlowe. Even though I loved the character, I hadn’t sought out Robert Altman’s adaptation of another Raymond Chandler Marlowe mystery, The Long Goodbye (1973), until now.

Updating the time period from the 1950s to the 1970s, The Long Goodbye sees Chandler’s classic private detective Philip Marlowe (Elliot Gould) try to clear his best friend, Terry Lennox, who is accused of brutally murdering his wife. Marlowe is himself implicated in the plot and accused of aiding a fugitive, having driven Lennox to the Mexican border the day before. Marlowe refuses to divulge any information on his friend’s whereabouts, but Mexican police find Lennox dead from an apparent suicide before Marlowe can reach him. Believing both the murder and suicide to be a set-up, Marlowe resolves to solve the mystery. Somehow involved are two subplots, which have Marlowe being asked to locate the missing alcoholic novelist Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden) and fending off gangster Marty Augustine’s demands for money owed by Lennox.

Unbelievably, the screenplay for Altman’s adaptation was written by Leigh Brackett who, along with William Faulkner, co-wrote the screenplay for Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep. Essentially what she’s done with The Long Goodbye is transport Marlowe from his gritty world of the 1950s to the early ‘70s, while maintaining his witty repartee and dry sarcasm, suit and tie, and 1948 Lincoln Continental. He is the classical Marlowe but clearly out of place. Next to his neighbors, young women who frequently ask Marlowe to pick up brownie mixes and practice nude yoga at midnight, Marlowe sticks out like a sore thumb. Altman and Brackett emphasize Marlowe’s incongruity with his surroundings by having him be the only character on screen to smoke, the only one in a dark suit in a world of flower power. Even his way of speaking is criticized by the film’s other characters. In this 1970s version of Marlowe’s seedy L.A., wisecracks are derided, as in a clever exchange with two police officers:

“He’s a cutie pie”

“No, he’s a real smart-ass”

“That’s what I mean”

“Why don’t you say what you mean?”

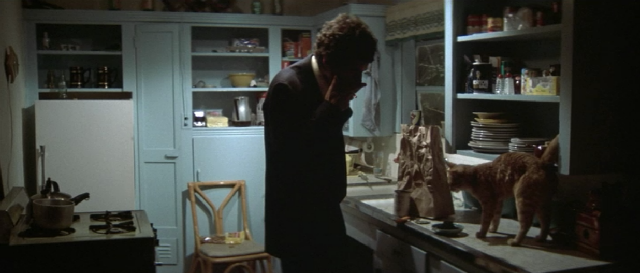

In this world of the gumshoe, quick quips and witticisms no longer bemuse his rivals. In Bogart’s era, a well-placed gibe would garner information. Gould’s Marlowe instead gets a beating. Both Marlowe’s make remarks only heard by the audience, but in The Long Goodbye these take the form of Marlowe’s ramblings to himself. The film is riddled with meandering dialogue, conversations and commentary that Marlowe says to himself. This reduces the element of mystery surrounding the Marlowe character and makes him much more human, compared to his Bogart counterpart. Gould’s Marlowe comes across as lonely, mostly because he has no one except a cat for company and he is lost in a wholly unfamiliar time period. Marlowe’s cat plays an important role in the film, as Brackett devotes the first ten minutes solely to a sequence in which Marlowe attempts to trick the cat into eating a different brand of food. In a film that can use as much time for exposition in the later mysteries, there is no reason to include this sequence except to establish Marlowe’s isolation.

All of this signals a shift in character from Bogart’s Marlowe and the literary Marlowe to Gould and Altman’s re-visioning of the character. The character at his core has always been principled, a moral romantic. The Long Goodbye sees Marlowe start off that way. Marlowe firmly believes that Terry Lennox was innocent and so investigates Lennox’s connections, against police requests. And moved by Eileen Wade’s search for her drunken husband, Marlowe takes on a second case. These actions seem in line with the original character, but the final act of The Long Goodbye introduces us to a completely different, emotionally charged Marlowe. Jaded by betrayal after betrayal, this Marlowe is personally affronted by the truth of the Lennox case. Seemingly his dearest friend is not the man that Marlowe thought him to be, and his lack of morals becomes a fault that Marlowe must personally, and violently, address. These changes in character are not part of Chandler’s original novel but the additions of Brackett and Altman. In adapting The Long Goodbye, they effectively deconstruct the classical Marlowe figure.

Among the many adaptations of Chandler’s Marlowe novels, The Long Goodbye still stands out today. Within the genre of film noir, the noir hero is largely untouchable. Cool and mysterious, he has unwavering principles, even if he does go against the police. In the end, he knows what is right and wrong and can impeccably judge situations and people. What Altman and screenwriter Brackett accomplish in The Long Goodbye is to undermine that assumption. Elliot Gould’s Philip Marlowe is just as capable of misreading people as anyone else, and the betrayal of his closest friends affects him on an emotional and moral level. Unlike previous incarnations of the character, this Marlowe is imperfect and very human.

– Katherine Springer