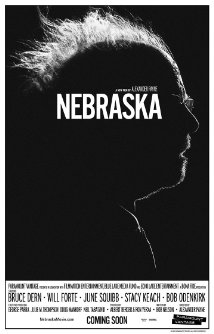

Written by Bob Nelson

Directed by Alexander Payne

USA, 2013

It’s become passé in popular culture to mock the elderly, to tweak and jeer at them just enough without being excessively cruel. We can laugh at old people for swearing at each other, or for having regressed physically to the point where they seem like overgrown babies who can barely dress themselves. It’s easy to laugh at our elders, swaddling ourselves in the fervent and foolish hope that we will never become like them. Time may march on and we may eventually hit the age when we qualify for Social Security and Medicare benefits, but we will never grow that old, that infirm. Thus, we can comfortably snicker at the foibles of old folks. For the opposite take, consider Nebraska, a deceptively simple character study that never once points and laughs at its elderly characters. It presents these people, the true salt of the earth, as they are, speaking and acting plainly. We may choose to associate their actions and words with a devious and almost mean comic tone, but only a few times does this movie stoop to the easy gag, thankfully.

Beginning in Billings, Montana, Nebraska focuses first on the taciturn, inward, and now wild-haired Woody Grant (Bruce Dern) as he attempts to walk to Lincoln, Nebraska, in the hopes of claiming a million-dollar prize from what is clearly some spam snail mail. Woody is unaware of this fact, he doesn’t care, or he doesn’t want to admit that he was once again fooled after a long life of awkwardness and pain, so he refuses to stop until he brings his “winning” ticket to the home office. To placate Woody, his youngest son David (Will Forte) drives him to Nebraska, stopping first in Woody’s hometown where he reunites with his family and long-ago friends, all of whom become greatly interested in his doings once he lets it slip that he’s after a cool million.

But the fruitless hunt for money is the catalyst for the real impetus behind Nebraska, at least through director Alexander Payne’s view: a final hurrah for the small towns that used to be the purest representations of America. Throughout his career, Payne has spent time honoring his home state of Nebraska, in films as diverse as Election and About Schmidt. With Nebraska, he’s crafting his last rites, a eulogy for the flat grasslands that still line the middle of the country, but are surrounded by countless ghost towns. Payne and cinematographer Phedon Papamichael have shot the film in black and white, which only emphasizes how dead places like Billings or Lincoln, or Woody’s hometown of Hawthorne are in the 21st century. As David and Woody walk through the main street in Hawthorne, it’s as if they’ve wandered into the setting of some warped horror story that begins in a town devoid of life. In these moments, the film evokes Peter Bogdanovich’s bleak yet artful The Last Picture Show, a film equally obsessed with the originally romanticized open spaces of the Old West where cowboys once thrived. Nebraska may not be as far West as Arizona or Utah or parts of Texas, but the empty, run-down, and ramshackle streets of Hawthorne speak to a wistfulness and longing for the past, as well as the painful reality that the modern world has no more need for these small towns or the old men who can’t abandon them.

Bruce Dern, one of our finest character actors, works internally as Woody, a man who is frequently not paying attention to the world around him or pretending to be lost in his own head. (In a number of carefully crafted shots, Payne allows for ambiguity; perhaps Woody is hearing his wife clearly about the number of times in the past when he screwed up.) Forte, best known for his work on Saturday Night Live, doesn’t have a showy part as David, but it’s his ordinariness that makes him stand out. Long gone are any vestiges of MacGruber or the other outsized and outrageous characters he performed on live television. David is a low-key sort, perhaps more sensitive than anyone else in his family; his seemingly unique qualities, though, are what may turn him as inward as his old man. Forte does a fine job with this straight-man role, never stretching or playing over the top. Heightening the thematic similarities between this and About Schmidt, June Squibb plays Woody’s wife, the long-suffering Kate. Woody is not so vocal about being perplexed that he’s still married to this person, not as much as Jack Nicholson’s Schmidt was to his wife in the 2002 film (also played by Squibb), but he’s as blasé about her presence. Squibb is excellent here, elevating the stereotype of the pushy wife who tends to nag into a full-blooded person. Her faceoff with Woody’s family is both expertly written, by Bob Nelson, and so confidently performed. What a shame it is that it took her so long to get such a powerful role.

But what a relief it is for a film like Nebraska to exist. Its simplicity is part of its power. Alexander Payne, in returning to his roots after an extended period off followed by a trip to Hawaii with The Descendants, has tapped back into his greatest quality as a filmmaker: his humanity. Like Joel and Ethan Coen, he has the ability to go home again, depicting the region-specific quirks of its denizens and admitting their strangeness without laughing cruelly at the people or their ways. Nebraska is a film so keenly felt and realized that its performers, even those whose prior work in film and television we may recognize and cherish, do not feel as if they’re acting, only being. Alexander Payne spent some time away from his home state, but with this new film, he embraces it wholeheartedly, honestly, and triumphantly.

— Josh Spiegel