As with any year, some people have begun arguing that 2013 was a bad year for film, because of the expected glut of effects-heavy blockbusters that litter the multiplexes each summer, or because there was a lack of auteur-driven storytelling for the majority of the year. Though it is indeed frustrating that studios hold their more prestigious films until the last month or two of this or any year, 2013 was an excellent year for film. You shouldn’t have to look first to Sound on Sight’s list of the 30 best films of 2013 for proof, but you should add it to the pile, no doubt. We asked our film writers to provide their personal lists of the 15 best films of the year; everyone’s number-one pick got 15 points allocated, everyone’s number-two pick got 14 points, and so on. (As you’ll see, the point values for each of the 30 films is included here.) Over 40 contributors sent in their lists; there were over 160 films that got points. So if that’s not proof enough, consider the following list and capsules as a reminder that 2013 was yet another banner year for cinema.

* * *

20. Pacific Rim (72 points)

Written by Travis Beacham and Guillermo del Toro

Directed by Guillermo del Toro

USA, 2013

There are some legitimate issues with Guillermo del Toro’s newest film, chief among them the lack of character development. A lot of the film’s issues can be expanded to issues with summer blockbusters as a whole. However, the best blockbusters manage to keep viewers entertained during their runtime enough to make these complaints a lesser issue, and in this respect, Pacific Rim wildly succeeds, with the movie running at a brisk pace and never sagging. But it’s not just that Pacific Rim is highly entertaining. The creatures are also a highlight; not only is their originality a refreshing oasis in a sea of reboots and franchises, but each new threat brings with it a different strength, ensuring that no two fights are alike. Add to that a unique mythology, and a colourful set of supporting characters including Ron Perlman’s Hannibal Chau, and under the watchful eye of del Toro, it all comes together to elevate the movie from standard summer fare to one of the year’s best.

— Deepayan Sengupta

19. Prisoners (73 points)

Written by Aaron Guzikowski

Directed by Denis Villeneuve

USA, 2013

For nearly 10 years, Prisoners passed through many a director and star (including Antoine Fuqua, Bryan Singer, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Christian Bale) before arriving in theaters, and it would be a challenge to imagine a team realizing the project with more tact than Denis Villeneuve, Roger Deakins, Hugh Jackman and Jake Gyllenhaal have. Through Deakins’ carefully calculated cinematography, Villeneuve weaves without restraint an engrossing tale of many-cornered violation. The director wastes little time placing us in the initially guiltless shoes of one both victim and aggressor with all but complete conviction, effervescing conflicting unease in the protagonism. This is without question Jackman’s movie, yet in memory, the performance standing out among the thoroughly excellent ensemble is Gyllenhaal’s as Detective Loki, an exceptionally simplistic character on paper whom the actor has rendered fascinating through subtleties and ticks. The compelling layers put forth in Prisoners demand attention and revisitation.

— Tom Stoup

18. A Touch of Sin (74 points–tie)

Written and directed by Jia Zhangke

China, 2013

Jia Zhangke rightfully walked away with a Best Screenplay award at the Cannes Film Festival for A Touch of Sin, an intricately plotted exploration of violence and corruption in contemporary China. Sin is a grim but poetic crime film, which the writer-director based on four shocking and true headline-making events he read while browsing the Internet for stories of violent crimes censored by the government. These stories reveal a growing restlessness between China’s new ruling class and the working class, and paint an artful condemnation of the Chinese state capitalism. All four stories centre around tragedies of a common man or woman, all set in different regions of China, and all ending in bloodshed. The men and women in each of its subsets are driven to violent ends while living in the world’s fastest-growing economy. A Touch of Sin ends on a note that is anything but hopeful; the four protagonists who feel imprisoned by China’s extreme social changes may never find a way out. Unlike the goldfish released in a stream, a snake crossing the highway, or the horse who breaks away from his abusive owner, these four drifters may never again feel freedom or know happiness.

— Ricky D

17. Side Effects (74 points–tie)

Written by Scott Z. Burns

Directed by Steven Soderbergh

USA, 2013

If Side Effects is Steven Soderbergh’s final theatrically released feature film in the United States (leaving aside the HBO film Behind the Candelabra, also excellent), then he went out on one hell of a high note. In its opening shot, this gradually nutso thriller evokes nothing short of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, a cinematic allusion that recurs surprisingly often throughout. First, Side Effects is the story of a depressed young woman (Rooney Mara) trying to maintain her sanity even after her loving husband (Channing Tatum) leaves prison after having been convicted of insider trading. Then, Side Effects is the story of her increasingly harried psychiatrist (Jude Law, delivering one of the year’s best, and most underrated, lead performances) and his inability to figure out what’s wrong with his morose patient. Then, it’s the story of the toxic effect pharmaceutical drugs have on both users and psychiatric pushers. Soderbergh and screenwriter Scott Z. Burns, tackling the medical community in a different, more focused fashion than in their recent disaster-thriller riff Contagion, have created in Side Effects a slickly entertaining and gleefully trashy juxtaposition of Hitchcockian and De Palma-esque stylistic touchstones. It is a nasty piece of work, and yet another reason why we should all hope Soderbergh reverses his choice to retire from features.

— Josh Spiegel

16. Captain Phillips (74 points–tie)

Written by Billy Ray

Directed by Paul Greengrass

USA, 2013

Director Paul Greengrass is a master of creating tension-filled films that grab you from the first scene and do not let you go until the end credits roll. His latest film, Captain Phillips, is no different. Captain Phillips tells the true story of Captain Richard Phillips, whose cargo ship was hijacked by Somali pirates in 2009, and his struggle to keep his ship and crew safe. What makes a film like Captain Phillips so successful is the way Greengrass is able to sustain suspense despite the film’s story being well known. Tom Hanks gives a performance that could easily rank among his best, just behind his work in Philadelphia or Forrest Gump. As the title character, Hanks is strong, committed, and offers an emotional range that he hasn’t displayed in some time. Equally great in his first role is supporting player Barkhad Abdi, who delivers a balanced performance that is equally menacing and vulnerable. Captain Phillips is a mesmerizing, suspenseful and dramatically rewarding experience.

— Matthew Passantino

15. Nebraska (75 points)

Written by Bob Nelson

Directed by Alexander Payne

USA, 2013

Though a few scenes with certain supporting characters bother on a scripting level, Alexander Payne’s Nebraska is a compassionate and sharply written odyssey that otherwise never strikes a false moment nor patronises. Its dry humour delights, but the real takeaway here is the exploration of repressed feelings, both loving and traumatic, and not just in the central relationship built around great turns by Bruce Dern and Will Forte. The former may not be on his last legs, but he certainly seems to be in his last stages of consistent engagement with the world around him, and the film finds touching beauty in its little portrait of strained loved ones finally finding some secure grounding to proceed with life. Also of note are the film’s relatable qualities in depicting the sparest of interactions with extended family members, in all their humorously awkward glory, and the return to the somehow still friendly ghosts of one’s past in the town of your youth.

— Josh Slater-Williams

14. Stoker (76 points)

Written by Wentworth Miller

Directed by Park Chan-wook

USA and UK, 2013

South Korean Park Chan-Wook’s English-language debut, Stoker, was heavily inspired by one of Alfred Hitchcock’s best, Shadow of a Doubt, in which a teenager’s mysterious seemingly jovial uncle comes visit the family for a while, although it soon becomes evident the uncle has a dark past that will change all of their lives. In this film, the teen is played by Mia Wasikowska, the uncle by Matthew Goode, with Nicole Kidman filling as the widow of the uncle’s recently deceased brother.

Whilst the over-arching plot follows Shadow of a Doubt with relative fidelity, that is where the similarities end. Park Chan-Wook, after wowing audiences worldwide with his Vengeance trilogy and Thirst, directs Stoker with all the panache and craftsmanship he can muster, as if it were the last project on which he would ever work. Concentrating on the young protagonist’s sexual awakening, which is intimately linked with her uncle’s suspected misbehavior, Stoker is a thing of beauty on multiple levels. Few films emerged in 2013 that sport this film’s beautiful cinematography and editing, both aspects working in tandem to construct an eerie, discomforting, yet nonetheless absorbing tone that inspire both worry and desire to see the characters’ journeys unfold. Wasikowska, Goode, and Kidman shine in their own ways, arguably doing career-best work, each distinct, memorable, representing a dark, alluring point of view on the horrifying family truth about to be unearthed from the past.

— Edgar Chaput

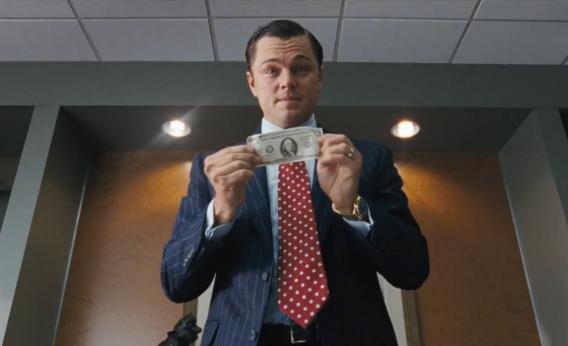

13. The Wolf of Wall Street (80 points)

Written by Terence Winter

Directed by Martin Scorsese

USA, 2013

On the surface, The Wolf of Wall Street could be a bawdy, extremely raunchy celebration of American excess, the pinnacle of bad behavior. Barely below that surface, however, is a commentary on the limits of that very excess, and how necessary it is for our society to have some form of checks and balances. Because the film is from Jordan Belfort’s point of view, presuming it endorses his attitude isn’t entirely outlandish. (And the way the narration, which sometimes bleeds into DiCaprio as Belfort breaking the fourth wall and facing the audience, is structured may present the notion that The Wolf of Wall Street, the movie, is a blank slate upon which Belfort will write, revise, and present his story to his satisfaction.) But it would be wrong to presume that Martin Scorsese has trod this exact ground before, in films such as Goodfellas and Casino and Gangs of New York.

No doubt, Scorsese is fascinated to the point of obsession with the nature of crime, the desire so many people have to break the law for their own good. Jordan Belfort is one of the most odious criminals he’s depicted in his many decades as a filmmaker, to the point that, in a number of lengthier diatribe-like monologues to his brokers, Belfort is presented as not an antihero, but a full-fledged villain. That may be Scorsese’s best trick in the film: fooling its subject to sign away his life’s rights only to be subtly damned on the silver screen. The Wolf of Wall Street is a grand, triumphant depiction of the entitled, near-insane proclivities of the super-rich and those who wish to be among the super-rich. But at all times, it’s exhorting us, the non-super-rich, to get mad once more at the financial institutions built to bilk us out of our cash, to be furious with the people who look at the middle class and the sober and find them wanting. It’s been a long time since a Martin Scorsese film felt so angry; anger never felt or looked so damn good.

– Josh Spiegel

12. Leviathan (82 points–tie)

Directed by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel

USA, France, and UK, 2013

Leviathan is an amalgamation of wonder and horror that overwhelms the senses with an inside look at how the commercial fishing industry operates in the North Atlantic Ocean. Just how relentlessly careless the fishing business is with the ocean’s resources is in full view as we see creatures cut, kicked, and killed en masse to meet the sprawling need of excessive modern consumption. The ghastly monotony of the enterprise sneaks up on the audience with a slowly rising dread of the continual parade of destruction. Often wallowing in the grisly scenes of slaughter from down on the blood-soaked decks, Leviathan doesn’t ever give the viewer much visual or audible reprieve. The abstract perspectives of the camera mesh with the sounds of nature’s rhythm to create a constant state of cinematic flux. The crashing waves, squealing machinery, and squishy thudding of fish being thrown about act in tandem to whisk the viewer through its demanding content. Anything but comforting, Leviathan is a silent witness to the cruel and unceremonious deaths of the creatures we consume that immerses us in an ethereal, poetic world that demands to be known.

— Lane Scarberry

11. The Act of Killing (82 points–tie)

Directed by Joshua Oppenheimer

Norway, Denmark, and UK, 2012

“Two wrongs don’t make a right.” As far as truisms go, it’s not a bad one, but it’s not a terribly useful one when it comes to film criticism, as Joshua Oppenheimer’s endlessly disturbing The Act of Killing proves. It’s difficult to dispute that, on a certain level, the film enables its subjects, who happen to be some of the most prolific, remorseless killers on the fact of the planet. But it’s equally difficult to deny that their social and political context has already enabled them to a much greater, and much more destructive, degree, and that the depths the film plunges into would not be possible without indulging the loathsome thugs at its center.

— Simon Howell