“Animal Man” (1988) #1-26*

Writer: Grant Morrison

Penciller: Chas Truog, Tom Grummett, Paris Cullins

Inker: Doug Hazlewood, Steve Montano, Mark McKenna

Letterer: John Costanza, Janice Chiang

Colourist: Tatjana Wood, Helen Vesik

Covers: Brian Bolland

*The specific details of #20-26 will not be discussed in the below article. If you’ve never read this comic before, don’t be afraid to read this. To appropriately write about this comic, early and middle narrative has to be spoiled, but the big end-game surprises are not given away here.

For some, the late 1980s-to-early-1990s is probably the creative highpoint in DC’s modern era of comics. A turning point for mainstream superhero comics in general, it saw a shift in tone and audience, appealing more to adult readers for its “gritty” and “realistic” depictions of the otherwise fantastical lives of superheroes. Frank Miller’s success on The Dark Knight Returns and Batman Year One and Alan Moore on Swamp Thing and Watchmen motivated DC to track down other young hungry artists with an original voice. The Moore-inspired “British Invasion” saw DC recruiting the talents of Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, Peter Milligan, and Jamie Delano. Just as DC handed Swamp Thing over to Moore a few years earlier, they did the same for Animal Man and Grant Morrison, and The Sandman and Neil Gaiman. It was a clever idea; give some of their promising young writers creative control over a forgotten or unimportant superhero from DC’s publishing history, letting them reinvent the character in their own way. As we know now, this paid off enormously well.

Morrison originally only intended to write a four-issue miniseries of Animal Man. Published in late 1988, it was about a struggling actor named Buddy Baker, husband and father of two children. After a freak accident from years earlier, he obtained a superhuman power: the ability to tap into the key characteristics of any nearby animal, which he could benefit from to a very heightened extent. After a former failed stint of being a third-rate superhero called Animal Man, Buddy dons the costume once again and gets mixed up in a bizarre situation surrounding a mysterious break-in at S.T.A.R. (Science and Technology Advanced Research) Labs, who might be conducting inhumane animal testing. Right from the start, Animal Man takes an uncommon approach for a superhero title and preaches animal rights, morally getting behind Buddy Baker’s beliefs.

This four-issue story has nothing in the way of world-threatening disasters (those are for the A-listers), but it does have bad men being really, really mean to animals, and that’s more than enough for Buddy. It’s a semi-serious comic brought down a peg by some jarring goofy qualities, particularly when it introduces B’wana Beast, a muscular loin-cloth wearing superhuman, who wears a flashy red and yellow helmet. Readers of Morrison’s Batman know of his fondness of resurrecting obscure characters from decades past (Batman of Zur-En-Arrh and Bat-Mite come to mind), and he does so here as well, giving second life to this long-forgotten Silver Age hero.

Had Morrison walked away from Animal Man after four issues it would not have become the legendary comic it is today. Fortunately its success prompted DC to keep running the series, now as a regular monthly, and they asked Morrison to keep writing. The next issue is the one to change everything. Aside from introducing Baker’s animal rights beliefs, and devoting a good portion to his home life, the opening arc contains very little of what made “Animal Man” the legendary comic it is today. The seeds are planted in #5, which presents the comic’s thesis in a single, self-contained issue, and thematically sets in motion an arc that wouldn’t be resolved until #26, Morrison’s final issue on the comic.

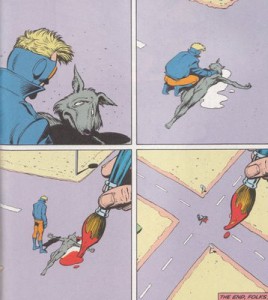

“The Coyote Gospel” is one of the greatest one-shots in mainstream comics, and an entire article equal in size to this very one could easily be spent discussing this one issue. At the heart of the story is an anthropomorphic coyote living in the desert, dying many deaths. He is run over by car, shot, pushed off a cliff, crushed by rocks, and suffers explosion by way of dynamite. Each time, he quickly regenerates and continues his tragic existence. If this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a thinly veiled parody of the Wile E. Coyote, and we later learn the Crafty, the coyote, used to come from a chaotic cartoon world, where consequence-free mayhem and destruction was the natural order of life. Upon rejecting this way of life, Crafty meets his God, and is punished for his sins: “’Then you must spend eternity in the hell above,’ said God. ‘While you Live and bear the suffering of the world, I will Make Peace among the beasts. That is my judgment.”’ The cruel Creator sends Crafty to inhabit the world of comics, where death and destruction is every bit as common place as the cartoon world, only the pain and suffering felt is much more “real”. Nonetheless, Crafty is content in his never-ending suffering, because he knows it was for a just cause: he saved his own world. “The Coyote Gospel” is as dense as one-shots get, and can be read in many ways; as a Christ parable, a critique on the senseless violence in cartoons, a critique on the expectations of comic book readers and the death and rebirth cycle of many comic book characters, a mere parody of the Looney Tunes, a meta-textual look at the relationship between the Creator and the Creation (the last one is explored a lot more directly in the groundbreaking 26th issue).

“The Coyote Gospel” is one of the greatest one-shots in mainstream comics, and an entire article equal in size to this very one could easily be spent discussing this one issue. At the heart of the story is an anthropomorphic coyote living in the desert, dying many deaths. He is run over by car, shot, pushed off a cliff, crushed by rocks, and suffers explosion by way of dynamite. Each time, he quickly regenerates and continues his tragic existence. If this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a thinly veiled parody of the Wile E. Coyote, and we later learn the Crafty, the coyote, used to come from a chaotic cartoon world, where consequence-free mayhem and destruction was the natural order of life. Upon rejecting this way of life, Crafty meets his God, and is punished for his sins: “’Then you must spend eternity in the hell above,’ said God. ‘While you Live and bear the suffering of the world, I will Make Peace among the beasts. That is my judgment.”’ The cruel Creator sends Crafty to inhabit the world of comics, where death and destruction is every bit as common place as the cartoon world, only the pain and suffering felt is much more “real”. Nonetheless, Crafty is content in his never-ending suffering, because he knows it was for a just cause: he saved his own world. “The Coyote Gospel” is as dense as one-shots get, and can be read in many ways; as a Christ parable, a critique on the senseless violence in cartoons, a critique on the expectations of comic book readers and the death and rebirth cycle of many comic book characters, a mere parody of the Looney Tunes, a meta-textual look at the relationship between the Creator and the Creation (the last one is explored a lot more directly in the groundbreaking 26th issue).

Following a super confusing cross-over with a story arc titled “Invasion!”, Animal Man continues a string of single issue stories with #7. “The Death of the Red Mask” is perhaps overlooked because it so quickly follows “The Coyote Gospel”, but it’s an outstanding one-shot as well about Animal Man trying to talk the depressed Golden Age former supper-villain out of killing himself. Once again, this is a comic about comics, and looks at the cyclic nature of superhero and super-villain stories through a more realistic lens. It makes sense that a villain, whose plans are thwarted again and again by the same heroes, for years on end, often in the same fashion (as this was the Golden Age), would experience existential turmoil and question the validity of his life.

Buddy Baker gets a startling revelation in #12, the end of a three-story story arc that challenges his perception of reality. He gets a visit from the aliens who caused Animal Man to be born, during his superhero origin, as they try and prevent pre-Crisis on Infinite Earths timeline characters from breaking through into the current continuity. Apparently, the aftermath of the Crisis left some “holes remained unseen”, and in the case of Baker, his pre-Crisis and post-Crisis lives began to clash, and threaten his own existence. This smart – if slightly confusing – story examines comic book universe ret-cons and shows just how life-changing it would be if these events became known to the characters being re-worked. It would have been great to see Grant Morrison return to these ideas in the post-New 52 landscape (though, perhaps it’s worth noting that the post-New 52 volume of Batman Inc. remains largely unaffected by the changes, opting to shy away from mentioning areas where the timelines have changed).

Because of the success of long-form comics like the 12-issue Watchmen and the 200-page graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns, longer stories in comics were becoming a lot more common place by the 1980s. The two, three, four (and more) issue story arcs were outweighing the one-shot, which nowadays are rare and usually just there to bridge the gap between arcs. What’s so remarkable about Morrison’s run on Animal Man is that it’s mostly one-shots; that he was able to produce so many memorable, compelling, dense adventures in just 24-pages. Morrison can pack a literary punch in one issue greater than many writers can manage in lengthy arcs, as seen in “The Coyote Gospel”, “The Death of the Red Mask”, and a later issue (#15) titled “The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”. In it, Animal Man joins a band of eco-terrorists who try and prevent a mass slaughter of dolphins. Animal Man previously preached the fair treatment of all animals, but saying and doing are two entirely different things; this issue more than any preceding it is Animal Man at its most pro-animal rights activist, and Morrison (a vegetarian and animal rights activist himself) appears to be in agreement with his title character. The issue follows not just Animal Man’s quest, but perhaps more poignantly it depicts the near-genocidal slaughtering from the perspective of an actual dolphin, as it narrates its own thoughts during this travesty.

The mysterious figure James Highwater appears briefly and sporadically throughout the comic leading up this his eventual meeting with Buddy Baker, in “At Play in the Fields of the Lord” (#18). Highwater takes Buddy to the Arizona desert, and after essentially tripping out on drugs, they experience a joint psychedelic experience wherein Buddy learns more about his superhero origin story and the Crises. In the following issue, Buddy Baker comes face to face with the pre-Crisis Animal Man, who warns him about the Creators who twist reality for the sake of entertainment. The Animal Man of the past fears his current nonexistence, and opens up Buddy’s eyes to the fragile state of his own reality, showing him the window that leers beyond the pages of the comic, as he looks straight into the eyes of the comic book reader. Comics before Animal Man have broken the fourth wall and comics after Animal Man have broken the fourth wall, but perhaps no other mainstream American comic has broken the wall in such an astonishing fashion.

The mysterious figure James Highwater appears briefly and sporadically throughout the comic leading up this his eventual meeting with Buddy Baker, in “At Play in the Fields of the Lord” (#18). Highwater takes Buddy to the Arizona desert, and after essentially tripping out on drugs, they experience a joint psychedelic experience wherein Buddy learns more about his superhero origin story and the Crises. In the following issue, Buddy Baker comes face to face with the pre-Crisis Animal Man, who warns him about the Creators who twist reality for the sake of entertainment. The Animal Man of the past fears his current nonexistence, and opens up Buddy’s eyes to the fragile state of his own reality, showing him the window that leers beyond the pages of the comic, as he looks straight into the eyes of the comic book reader. Comics before Animal Man have broken the fourth wall and comics after Animal Man have broken the fourth wall, but perhaps no other mainstream American comic has broken the wall in such an astonishing fashion.

Animal Man is a comic about a man who repeatedly has to come to grips with his not-so-real reality. Buddy Baker: husband, father, superhero. He wants more than anything to be Animal Man and to live the exciting superhero life. Fate had different plans, however, when it bestowed upon him Grant Morrison as his writer (and for the sake of this comic, Creator). Animal Man is a superhero who doesn’t get to experience superhero adventures, just as Animal Man is a superhero comic that isn’t really a superhero comic. It’s a comic about a character gradually realizing that he’s in a comic, which to him feels like Hell itself. For all of its wit (the dry variety usually associated with Morrison), this is a deeply sad comic, as Grant Morrison, the Creator, puts his Creation through repeated agony all for the sake of entertainment, challenging and even breaking Buddy Baker’s faith (and later: will to live). Animal Man is a comic about comics, and about the relationship between the comic book writer and the comic book reader. Animal Man is one of a kind.