The Canterbury Tales

Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Written by Pier Paolo Pasolini

1972, Italy

The Canterbury Tales (1972) is the second film in Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life” that began with Decameron (1971) and Arabian Nights (1974). Each film in the trilogy contains an enormous amount of sex, nudity, slapstick, and scatological jokes and are based on revered works of literature. Pasolini’s adaptation of Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales” contains eight of the 24 stories from the book. Each story effortlessly flows from one to the next and the whole is certainly greater than the sum of its part. Pasolini was a terrific director and his later period shows how he expanded his political cinema by incorporating the Academy’s literary canon. Adapting revered novels did not stop Pasolini from inserting radical subversions into the ideology of these texts.

In The Canterbury Tales, a fictional Chaucer, played by Pasolini, frames the narrative, writing them in the film as the images appear. Pasolini is showing us a film in the register of enunciation, an attempt to make his narrative deliver itself in the present tense register. Near the end of the film, Pasolini’s Chaucer writes that these stories were written for the sake of storytelling itself. Art of art’s sake, entertainment for the sake of entertainment proclaims the film, “told for the sole pleasure of telling”. Watching stories unfold whose sole purpose are for the pleasure of storytelling is the best way to approach this film.

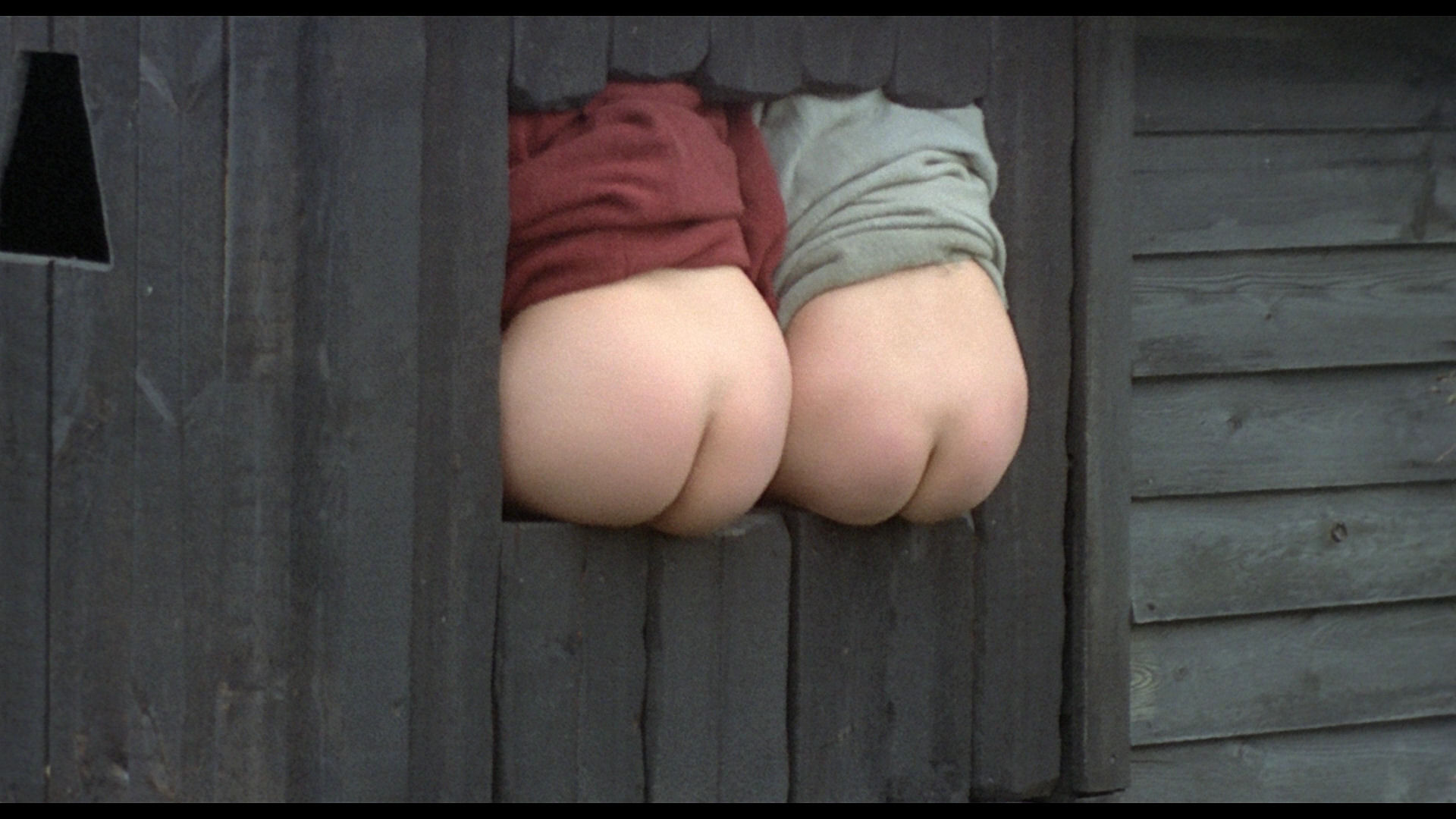

The episodes are completely self-contained with no characters showing up in other stores. Nearly all of the stories are comedies and Pasolini interjects many sex scenes throughout with an abundant amount of full frontal nudity. This extravagant use of nudity was copied by British filmmakers making soft-core porn comedies that lacked the political conscience of Pasolini. However, this is to be expected in late-capitalist culture which is defined by pastiche, parody with a blank mask, effectively diluting the political critique of Pasolini’s great work. Pasolini used farce, nudity, and sex to expand the frame of cinema by including images that were repressed and censored by capitalist film industries. Much like how surrealism included that which was excluded from bourgeois culture, Pasolini featured graphic images of sex, scat, piss, and vomit to shock viewers, showing spectators what was not allowed in bourgeois cinema. This film resulted in several court cases dealing with sex and nudity in films and allowed future films to enjoy less censorship than before.

Even though Pasolini is making a period piece the film feels of its time and almost anachronous in moments. For example, the fourth section features a character that is parodying Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp. This section was brief in Chaucer’s text but Pasolini greatly expanded on it to create this farcical, slapstick sequence. Not only does Pasolini reference cinema but he also injects his own Marxist politics into his seemingly apolitical soft-core porn parody. During the sixties Pasolini was an outspoken political writer in many debates happening in Italy including debates around the use of art, especially cinema, in political struggles. In the second story a man is condemned to burn to death for committing sodomy. Unlike the other man caught with a prostitute this man was unable to bribe the officials. In Chaucer’s political context religion, specifically Christendom, was a strong determining structure in society almost as strong as class conflict especially because this era predates capitalism, the revolution of the bourgeoisie. Sexual sins, especially sodomy could not have been dismissed with bribes. Pasolini focuses on the act of bribery, the power of wealth to override ethical transgressions. Sodomy is intertwined with being poor, being on the wrong side of the class struggle. The sodomizer is burned to death in front of the people. This scene depicts how homosexuals and the poor were regarded during the time of this film’s production. Pasolini is showing the audience a real, concrete “hell” that is more terrifying and sadistic than the “hell” depicted in religious ideology which is mocked in a great scene that rivals even Luis Bunuel’s attacks of Catholic ideology.

The Canterbury Tales has several instances of scatological humor, so much that it is difficult not to consider the point of it especially since it was another that Pasolini added when adapting Chaucer’s work. The scatological jokes are part of a larger element in Pasolini’s treatment of the material which involves focusing on the body. Pissing, defecating, and defecating are activities that connect humans with animals and humans simply animals. We do not have bodies but we are bodies. Pasolini depicts individuals as animals with consciousness but one that is directed toward bodily drives. The drive to fornicate is much stronger than the drive to obey societies rules dictated by marriage and religion in this film which is another contemporary touch that Pasolini added to Chaucer’s material. Sexual desire trumps everything in Pasolini’s narrative and for the most part drives the separate stories. Mixed in with this are choice placements of scatological humor like when Alison farts in Absalom’s face when he thinks he will get a kiss or when the three boys, having just finished having sex, piss on the women eating dinner in the common area of the hotel. The finale in hell also mixes sex with scat humor as demons shit out friars while others are having sex with priests.

Even after a film that is filled with hilarious sex scenes and distasteful fart jokes and bizarre episodes of violence the finale arrives like a punch in the face. Framed in a wide shot, Pasolini shows this vision of debauchery, a fully realized depiction of what Catholic ideology calls hell and it is hilarious.

– Cody Lang

This article is part of a two week spotlight on Pasolini.