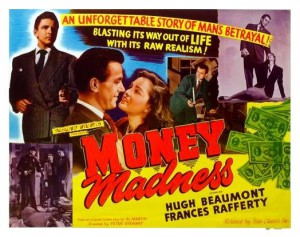

Written by Al Martin

Directed by Sam Newfield

U.S.A., 1948

Steve Clark (Hugh Beaumont) arrives to town with a hefty sum of money acquired through clandestine activities as well as mounting pressure from former cohorts who want their share of the loot. In true con artist fashion the runaway begins a covert operation to protect what’s his. First, he temporarily stashes the cash in a safety deposit box. Second, he earns a job as a taxi driver, thus permitting him to easily and safely encounter a great number of new faces, any one of which might prove a useful pawn. Third, happenstance has it that he meets the lovely but distraught Julie (Frances Rafferty), a twentysomething single woman living with her bitter, cantankerous aunt. When she stumbles onto Steve, Julie is smitten by his smile, desire to support, and his willingness to see her freed from her aunt’s clutches. The plot to get money suddenly becomes a plot involving murder!

There are some films for which the themes come through together wonderfully through the various, expertly coordinated aspects of the filmmaking process. The script is intelligent, the acting brings the characters to life, the music helps tell the story, the direction is confident, the cinematography sets the mood, and so on and so forth. It stands to reason that those are the good-to-great films. Conversely, there exist films that cannot claim to showcase the best and brightest of the many elements that lend to great cinema yet still somehow manage to have interesting thematic texture, a key ingredient that help said pictures avoid being tossed onto the cinematic scrap heap, unworthy of remembrance or discussion. Sam Newfield’s Money Madness falls squarely in the latter category, a motion picture handicapped by some less than stellar acting and production values that fail to conceal what appears to be a very limiting budget, but nonetheless takes an pertinent angle at the issue of male-female relationships of the era in ways that can find value in the modern age.

Part of the issue with Newfield’s movie is that it reveals in the opening minute that one of its characters is to be sentenced to prison for playing a role  in someone’s murder. In thrillers and other such films that aim to provoke tension, this strategy should serve to augment the viewer’s stress level given that everything that follows this opening scene operates much like a ticking time bomb. The people watching the film have a clear enough idea as to when the explosive device shall take effect, and actively fear for the livelihood of the endangered characters in its vicinity. Sadly, Money Madness sleepwalks through much of its first half, failing to elicit much suspense out of Steve’s fateful and obviously life-altering encounter with poor Julie. Several scenes play quite flatly, lacking the necessary momentum to raise the stakes appropriately, what with a leisurely atmosphere dominating the proceedings. A case could be made that such a pace and tone works in favour of the sharp turn the film takes later on, but then why plant the seeds of darkness in the opening minute if only to spend so much time making what amounts to a romantic drama?

in someone’s murder. In thrillers and other such films that aim to provoke tension, this strategy should serve to augment the viewer’s stress level given that everything that follows this opening scene operates much like a ticking time bomb. The people watching the film have a clear enough idea as to when the explosive device shall take effect, and actively fear for the livelihood of the endangered characters in its vicinity. Sadly, Money Madness sleepwalks through much of its first half, failing to elicit much suspense out of Steve’s fateful and obviously life-altering encounter with poor Julie. Several scenes play quite flatly, lacking the necessary momentum to raise the stakes appropriately, what with a leisurely atmosphere dominating the proceedings. A case could be made that such a pace and tone works in favour of the sharp turn the film takes later on, but then why plant the seeds of darkness in the opening minute if only to spend so much time making what amounts to a romantic drama?

The motion picture’s cast is something of a mixed bag of talents, only reinforcing the first half’s mediocrity. Frances Rafferty, a delightfully pretty actress, is a bit stiff in her delivery, the inexperience of youth showing one time too many. Once again, a case can certainly made by some as to why such qualities can be taken as a positive, a stronger performance would have helped make the character’s dilemma come through all the more effectively. On the flip side, Hugh Beaumont is very convincing as Steve Clark, the quintessential con man. The actor can turn on a dime, exuding warmth and charm one moment and dangerous assertiveness the next. It’s easy to imagine how a confused and impressionable young woman would fall for the chap, just as his maniacal side sends shivers down one’s spine.

When the aforementioned shift in mood occurs Money Madness finally engages with though-provoking material that adds far more complexity to the film than previously imagined. Simply put, the strategy Steve employs to get his hands on his prize mirrors the unhealthy attitude of a domineering husband towards a wife. While many noir films relish in the implicit and often explicit power struggles exercised between the sexes, a struggle frequently blanketed in overt sexual tension, rarely is said battle contextualized in so brutally understandable a manner as is the case in Newfield’s film. The man’s controlling nature under the present circumstances is for the sake of avoiding the authorities as well as enraged former partners in crime in a quest to get away scot-free with tons of cash, but to do so he must put his wife in a tight spot. Having killed off Julie’s aunt, which leads to the former inheriting the departed’s house, the villain plants the safety box in the home to make it seem like the money had been left for Julie all along. From that point onwards Steve makes his intentions quite clear, putting on an exorbitant amount of pressure on his once beloved. The husband’s initially kind demeanor is eschewed for a much for brutal, forceful attitude, befitting of a bitter husband that gets off of commandeering a marriage with a merciless iron fist. The analogy is a poignant one not just for its realism but for its unfortunate timelessness. Unbalanced share of power favouring the male and general lack of respect and understanding towards women was a problem long before Money Madness was released in 1948 and continues to afflict the state of matrimony till this day. If the film’s potency as commentary on the inequality of the sexes were a time capsule the film would still have worth, but its appalling relevancy in the modern age makes the film all the more interesting to watch for its timelessness.

When the aforementioned shift in mood occurs Money Madness finally engages with though-provoking material that adds far more complexity to the film than previously imagined. Simply put, the strategy Steve employs to get his hands on his prize mirrors the unhealthy attitude of a domineering husband towards a wife. While many noir films relish in the implicit and often explicit power struggles exercised between the sexes, a struggle frequently blanketed in overt sexual tension, rarely is said battle contextualized in so brutally understandable a manner as is the case in Newfield’s film. The man’s controlling nature under the present circumstances is for the sake of avoiding the authorities as well as enraged former partners in crime in a quest to get away scot-free with tons of cash, but to do so he must put his wife in a tight spot. Having killed off Julie’s aunt, which leads to the former inheriting the departed’s house, the villain plants the safety box in the home to make it seem like the money had been left for Julie all along. From that point onwards Steve makes his intentions quite clear, putting on an exorbitant amount of pressure on his once beloved. The husband’s initially kind demeanor is eschewed for a much for brutal, forceful attitude, befitting of a bitter husband that gets off of commandeering a marriage with a merciless iron fist. The analogy is a poignant one not just for its realism but for its unfortunate timelessness. Unbalanced share of power favouring the male and general lack of respect and understanding towards women was a problem long before Money Madness was released in 1948 and continues to afflict the state of matrimony till this day. If the film’s potency as commentary on the inequality of the sexes were a time capsule the film would still have worth, but its appalling relevancy in the modern age makes the film all the more interesting to watch for its timelessness.

When push comes to shove, Money Madness is an uneven picture. That said, a smart film is something that should always be welcomed with open arms by cinephiles. Sam Newfield’s endeavor does show that it has some brains to go along with an impressionable lead performance. Unfortunately, the project is handicapped by a somewhat cheap look, a middling female lead, and a first half that struggles to help the promised hard edge develop. As has been argued many times before though, a film that finishes strong is better than one that starts off promisingly only to squander the potential.

-Edgar Chaput