Written by Maurizio Braucci

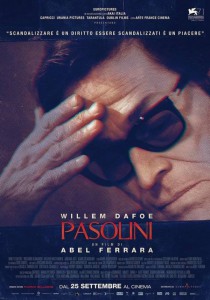

Directed by Abel Ferrara

France/Belgium/Italy, 2014

With the release of two films in 2014, Abel Ferrara has had one of the biggest years in his long and rich career. Welcome to New York, which premiered at the Cannes film festival, was a confrontational splash that divided audiences and critics alike. As the Toronto International Film Festival was underway, the film jumped back into the headlines too, as Ferrara began a media fight over the negotiation of an R-rated cut of the film, which he refused to endorse. This revelation came at a particularly apt moment, as Toronto presented Ferrara’s second film of the year, Pasolini. It seemed only appropriate that, while waging a public battle over censorship, Ferrara’s new film about a man rumoured to have died because of his art would be premiering.

When Ferrara announced his next project would be a biopic about the famed and controversial filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, it was clear that this was going to be anything but traditional. With obvious reverence for Pasolini’s daring art and philosophy, Ferrara attempted to channel that spirit of innovation and confrontation as much in form as in content. While the film explores the last days of Pasolini’s life, it adopts a non-linear and loosely structured style. The focus of the film rests on Pasolini’s words above all else, taking to heart Pasolini’s self-identification as a writer – a term he used to encompass all his varying talents and passions.

This works to mixed effect with scenes recreating Pasolini’s ambitious unmade project stalling the momentum. While Ferrara’s best work evokes a certain sense of the phantasmagoria, the dissolve between reality and dream, it is by no means done in a style at all reminiscent of Pasolini. This creates a bizarre dissonance for these recreation scenes, as they end up reflecting neither the style of Pasolini nor of Ferrara, which only distances the viewer and interrupts the flow of ideas. While Pasolini’s themes still manage to shine through with creative verve, visually these sequences are flat and distracting, a great shame as they drag down an otherwise adventurous film.

The film’s best moments are the ones that evoke landscapes of the mind, sequences in which Ferrara — without ever losing a grip on reality — manages to evoke the imagination and emotions of his characters. In these sequences images shift and overlay, as do sounds, to create a third idea. Ferrara uses these both to bring to life sensuality, as he suggests and explores Pasolini’s sexuality which made him an even greater target, as well as his world of ideas. As these concepts meet, we are left with an impression of who Pasolini was. Ferrara is far less interested in life incidents as much as he is the spirit of the man, and the power in which he faced his opposition.

Some of the best scenes of the film similarly focus on Pasolini’s relationship with friends and family. We see a man on a quest for intimacy, who feels somehow at a loss when he cannot express himself through writing. There is nothing overt about the exploration of his doubts, but they quiver below the surface, and it is through Willem Dafoe’s on-point performance as Pasolini that they are allowed to simmer and grow. While far from a perfect film, Pasolini reflects both the daring nature of its subject and its maker. While it lacks the punch of Welcome to New York, it is a rare piece of reflection from Ferrara, and appreciation for the film is likely to only grow over the years.

– Justine Smith

Visit the official website of the Toronto International Film Festival.