Written and directed by Amir Bar-Lev

USA, 2014

Happy Valley is the very definition of a documentary whose parts are greater than their sum. At every turn, the viewer can sense a much better film that could have been, tantalizing possibility lurking in the margins. The Penn State sex abuse scandal and its aftermath suggest so many things (not many of them terribly flattering) about American culture, specifically its football and college culture. But a lot of these themes are more gleaned by the viewer from what they see in the film than they are actively explored by the film proper.

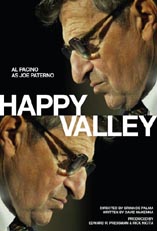

For over 40 years, Joe Paterno was head coach of Pennsylvania State University’s football team. He pushed his players to both athletic and academic excellence, and made Penn State a titan of college football. He was revered nationwide, but in Penn State and the surrounding area he was all but a god. And then it came to light that former assistant coach Jerry Sandusky had raped numerous young boys during his tenure, and that Paterno and other school administrators had known of at least one molestation incident, but hadn’t reported anything to the police. That’s when everything came crashing down; Paterno was fired, he died of cancer three months after the scandal broke, his name was removed from programs, awards, and buildings, and many of the team’s wins that came under him were stripped away by the NCAA.

Even though Paterno is no longer around, he is the focus of Happy Valley far more than Sandusky. And when you see the cult of personality around the man, you understand why. The Penn State scandal is a riveting dual study in both hero worship and institutional scapegoating, and how both exist within the all powerful system that is college football. Administrators were eager to give Paterno the boot in order to move past the controversy as quickly as possible. In contrast, the students of Penn State and the citizens of State College, PA rallied to support Paterno. They either did not care or denied that he knew Sandusky was a child molester and didn’t inform the authorities. They showed up to his house to cheer him. They rioted after his firing, overturning a news van at one point.

As depicted in this documentary, the football fan culture of Penn State is just one ladder rung short of utter psychosis. The throngs of people are raving devotees of a blood cult, with the child sacrifices taking place in the back rooms instead of in the open. These men and women, both young and old, don’t care one whit about Sandusky’s victims, though they pay lip service to them out of grudging obligation a few times. All that matters is the game, the win. And this is something endemic not just to this one university, but to American football worship as a whole. When the president of the NCAA lectures on the need for Penn State to reflect on its culture, it’s bitterly ironic, since they were perfectly modeling football culture.

The best parts of Happy Valley involve Penn State / State College students and residents hanging themselves with their own words, often setting themselves on fire or drawing and quartering themselves, too. At every turn, they model blithe white privilege — an artist who has to modify a mural that includes Joe Paterno calls erasing the halo over Paterno’s head “the hardest thing [he’s] ever done.” Students weep openly upon hearing that Penn State has been barred from cup games for four years. When a man protests a statue of Paterno with a small sign, visitors who want to take pictures with it heap frightening vitriol on him. It’s all hilarious and deeply sad at the same time.

Happy Valley mainly unfolds its story via traditional means, often letting interview subjects, especially Paterno’s family members, talk for far too long. It seems to shift its tone to match each point of view, in lieu of having a true point of view of its own. Both Paterno’s grown children and Sandusky’s adopted son (his only victim to speak to the filmmakers) get their own sad music playing along with their words. There’s nothing wrong with acting in an observational mode, but this doc misses out on saying something that could have left a truly lasting impression.

– Dan Schindel

Visit the official website of AFI Fest.