Almost every winter my family and I travel up to a cabin in Wisconsin Dells, and it serves as a great middle ground for our cousins who live in Iowa. The task predictably falls to me to bring some movies for the weekend. One of the films I wanted to introduce to my extended family was Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away.

Within about 15 minutes of the movie beginning, my uncle was out. “That movie’s just a bit too weird for me.”

As a newly minted teenager, it’s safe to say I probably didn’t even understand the concept. Too weird? If a movie told a story and was interesting, could it also be weird? Nerdy kids at school were weird. Bugs and vegetables looked weird. And anything weird was not typically a good thing.

In fact, I had already seen many classically weird movies. The bitingly sarcastic Wicked Witch of the West and Dorothy’s trippy voyage through Oz, a Beatles Yellow Submarine movie that screamed psychedelia, the bizarre parodies and references of Kubrick films on The Simpsons I couldn’t begin to understand: these are films that parents sometimes balk at for their deeper meaning, but that don’t faze children in the slightest.

Maybe it was just being that age at that point in time, but something about Spirited Away clicked. It depicted things that were odd, ugly, absurd and terrifying in a way I didn’t realize movies could be. For me Spirited Away was not a film that made me love movies, but one that showed movies, or for that matter works of art, could be something more.

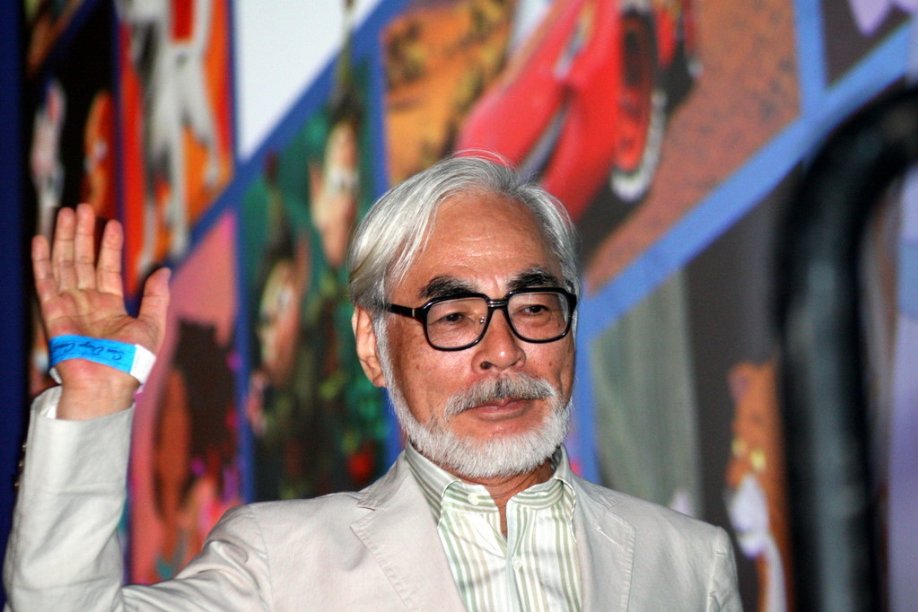

On a superficial level, Spirited Away carried with it a special clout as something more than just a movie, more than just a cartoon. On the DVD my dad purchased in 2002 and that we still own, John Lasseter gives a brief introduction to the movie by saying, “You are lucky. You get to watch Spirited Away.” He called it a masterpiece, which was unusual for any new film, let alone a cartoon. He touted Miyazaki as a master, and if you’re 12 years old and can name another auteur beyond George Lucas or Walt Disney, good for you. Both film and director stood out as something one of their kind.

It was also one of the first foreign films I had ever watched, or at least one that made an impression. Pokemon was from Japan, but Spirited Away, even with English dubbed dialogue, is unabashedly Japanese. Lasseter, Disney and Pixar go to unusually great lengths to produce English language versions of many of Miyazaki’s movies, and while I’ve defaulted to the Japanese version for most of his others, Spirited Away somehow still seems right to me in English.

The movie itself though, even 13 years removed, is as shocking, unexpected and even disturbing as anything you might imagine a kid raised entirely on Disney movies would find remarkable. It is full of depth, surprise, imagination and technical craft I couldn’t have begun to appreciate at my young age.

Even the film’s first shot is unusual, a close-up of a bouquet of flowers, hardly an establishing shot, with the movie’s little star Chihiro reading from a card, indicating that she’s moving away from her friends. Not only is this girl dealing with loss, but she’s also shockingly unlikable. Immediately she comes across as stubborn, spoiled and picky, and yet the way her parents behave and the conditions she’s under make her feel somewhat relatable. Can you think of any protagonist in a major Disney film that’s as polarizing as Chihiro at the start of this movie?

Chihiro’s character isn’t the only thing that seems a little off. The parents seem just as flawed and oblivious, the camera shoots from distinct low angle perspectives and unsettling framings that lead you to believe something isn’t right, and the movie’s fairly exhilarating opening as the father drives through the forest and then proceeds to venture into the unknown never truly hints what the film is on about.

Miyazaki introduces rules, ultimatums and scenarios that are never fully explained, like why Chihiro needs to eat spirit world food lest she disappear, or how if she breathes while crossing a bridge she’ll be spotted. This isn’t just Miyazaki thinking little of his younger viewers; we genuinely don’t question it.

Rather, the movie is full of splendor and wonder. It has an animated look that to this day feels distinctive. The way the water glistens, or how flowers scurry towards the frame as Chihiro and Haku dart through the fields, or this assortment of spiritual creations that puts the Mos Eisley Cantina to shame. Even the stranger and scarier characters, like the massive head and nose on Yubaba or the sludge caked river spirit, are so fascinating to observe.

The beautiful trick of Spirited Away is Miyazaki’s deft handling of tone, finding offbeat, cutesy humor in moments of gross tragedy, bloodshed and even violence, while maintaining his sinister air of mystery. This is a movie where a frog shaped black hole of a monster eats whoever gets near him and projectile vomits on whomever is in his way. This is a movie where a dragon dripping blood from his mouth is as memorable as a tiny little ball of soot getting crushed by a piece of coal. Adorable and repulsive are not adjectives you would use conjointly, but at times they both apply here.

The question is whether or not Spirited Away is actually a kid’s film, or just an amusing fable for young adults and their parents. Speaking from experience, this is a movie that can leave a lasting impact. Throughout the entire film, Chihiro is tested and taunted, the victim of losing her parents, home and even her own name. And rather than simply punish a spoiled little brat, Chihiro grows naturally into such a forthright, selfless and confident hero. It’s a message movie about love, memories, manners, adventure, respect and a dash of environmentalism, but it would be impossible to sum up in some storybook ending.

To see anything like Spirited Away truly is weird. Movies aren’t supposed to be this strange, this nuanced, this complex, this fantastical, or this symbolic. They’re supposed to be simple, funny, entertaining, and maybe just a little sad. All of Miyazaki’s movies dare to do more and beg the important distinction that even the weird can work.

For this child, Spirited Away just happened to be the first to prove movies could.