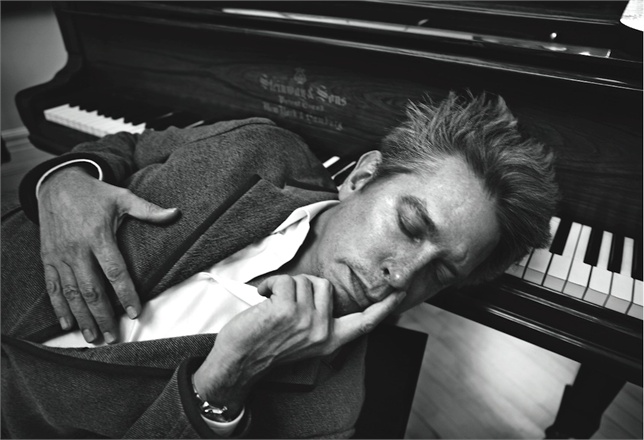

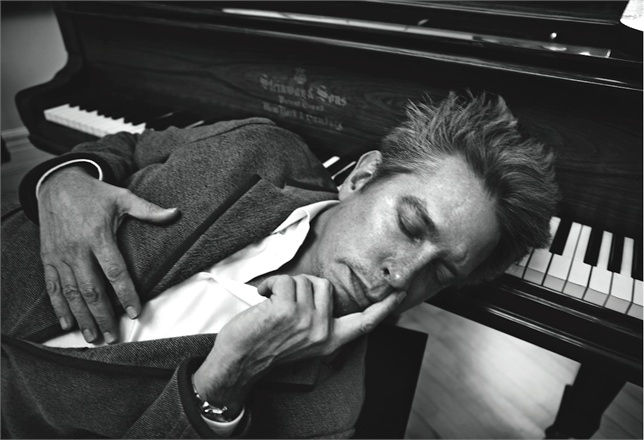

Elliot Goldenthal

One of the most prolific composers from the 90’s, Elliot Goldenthal might just be the unlikeliest to have ever received the call from Big Hollywood. Groomed by jazz legend Aaron Copeland and with a background immersed in ballet and opera, the Brooklyn native’s dissonant, often cacophonous sound just hasn’t flown in today’s fast paced electronic soundscape. Fortunately, Goldenthal’s repertoire is as diverse as his talents. While more orchestrally traditional works like Interview with the Vampire, Alien 3, and Sphere skew to the gothic, his scores for action fare Demolition Man, SWAT, and Heat demonstrate a malleability with more playful, edgy melodies. Needless to say, though the man has focused more on the world of musical theatre as of late, his talents are too singular to not be heard on the big screen again. After all, how many film composers have been nominated for a Pulitzer?

Who Should Give Him a Call: Goldenthal’s most recent collaborations have been with filmmakers who have worked with him before, namely Julie Taymor and Michael Mann. A brief rumor hinted that he would be scoring Mann’s Blackhat, but we know now that Atticus Ross got the job. It’s been years since Goldenthal went pitch black, so seeing him tackle a mood piece from a Denis Villanueve type or go humongous with the next superhero adaptation from DC would revitalize both genres.

Best Introduction to the Composer: The best foray into his work might be for Julie Taymor’s Titus, which runs the entire gamut of his abilities: vibrant jazz, thrashing rock, and orchestral bombast.

[vsw id=”u3Z6Qvtn1WM” source=”youtube” width=”640″ height=”375″ autoplay=”no”]

Mark Mancina

The brassy, busy orchestra/synth one-two punch of today’s blockbusters owes everything to composer Hans Zimmer, whose Remote Control Productions has populated the film world with artists like John Powell, Steve Jablonsky, and Ramin Djawadi. Of Zimmer’s many disciples, none were more suited for the frenetic, music video pathos of 90’s action filmmaking than Mark Mancina. Trained as a classical guitarist, his first big scoring year came in 1994 with Speed, which catapulted him to scoring virtually every modest action blockbuster of 1995 (Bad Boys, Assassins, Fair Game, Money Train) and breaking out to huge projects like Twister and Con Air. His rock and roll sensibility with a classical twist lent heart-pumping rhythms themes with actual heart, making his films some of the most musically enjoyable of the 90’s.

Who Should Give Him a Call: Since then, Mancina has been relegated to the wasteland of hack animated movies like the Planes series and hackier TV like Criminal Minds. His best option: return to what he does best. It would be great to see Michael Bay give him a call to kickstart the inevitable Bad Boys III.

Best Introduction to the Composer: Speed is an all time classic and Twister is loads of fun, but Bad Boys is the place to start, especially his relentless footchase piece.

[vsw id=”2TeWjy_w3PY” source=”youtube” width=”640″ height=”375″ autoplay=”no”]

Michael Nyman

Minimalism isn’t exactly the most sought after musical styling for Hollywood. Yet a composer as striking as Michael Nyman cut a small tear through the film world some twenty years ago with powerful compositions for films ranging from award winners like The Piano to bold stories like Gattaca to batshit experiments like Ravenous. One need only look at his two biggest collaborators–Peter Greenaway and Michael Winterbottom–to see his range. Whether methodically consonant in Greenaway pictures like The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover or richly textured in Winterbottom epics like The Claim, Nyman can turn the simplest story into layered, everlasting art. He has contributed his talents lately to documentary work and opera.

Who Should Give Him a Call: Nyman works best when he isn’t being pigeon-holed, so a humanist sci-fi project or offbeat indie drama would serve him well to get back in the game. But some Nyman is better than none, so hearing his swooning talents in the latest period literary romance–the next Jane Austin of Charlotte Bronte adaptation–would be music to the film world’s ears. Dream collaboration: Nyman teaming with Terrence Malick!

Best Introduction to the Composer: It has to be the moody beauty of Gattaca, whose somber yet uplifting melodies probably launched a thousand future film composers.

[vsw id=”6LeB8_by65A” source=”youtube” width=”640″ height=”375″ autoplay=”no”]

Graeme Revell

On the surface, Graeme Revell seems like another generic relic from the 90’s, but his workmanlike approach has been sorely missed in the realm of modern day assembly line composers. A veteran of genres from horror to action to thriller, Revell excels by blending into the tapestries of his film projects. Need a catchy sci-fi beat? A brooding superhero hook? How about some slam bang staccato riffs? Small or big, his virtual ubiquity made him a valuable asset of films like The Crow, Strange Days, Red Planet, and Pitch Black. The last few years have seen him wading in the anonymous waters of television, scoring hit shows like Gotham and CSI: Miami. However, his true talent lies in making films sound better than they have any right to.

Who Should Give Him a Call: Revell returned two years ago with the third outing in the Riddick series, but it would be great to see him elevate any of the myriad of dull thrillers that Hollywood pumps out year after year. Wouldn’t the latest McG stinker, Phillip Noyce escapade, or Liam Neeson vehicle benefit greatly from a sound other than repetitive plodding?

Best Introduction to the Composer: Forgettable movies often produce forgettable scores, but 1997’s rendition of the TV show The Saint allowed Revell to produce one of the most romantic–and thanks to the film, predictably forgotten–themes of modern movies.

[vsw id=”i_asEP69DMg” source=”youtube” width=”640″ height=”375″ autoplay=”no”]

Edward Shearmur

If there ever was a composer poised to break out who became a victim of Hollywood’s “we just don’t know what to do with you” mentality, it’s Edward Shearmur. Long relegated to middling, made-to-be-dismissed pictures, Shearmur’s musical identity was buried in the trash he was scoring. Needless to say, this was a composer trapped between indie prestige (The Wings of the Dove, Things You Can Tell Just By Looking at Her) and low level thrills (Charlie’s Angels, The Skeleton Key). So when he would surface every now and again with a rousing piece of untouchable greatness, say Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, The Count of Monte Cristo, or even Reign of Fire, the question would pop up: who is this guy? With heartfelt, bold, and often melancholic works, Shearmur is a chameleon like Graeme Revell but with the soul of former pros like Jerry Goldsmith. That he has mostly scored tripe like 88 Minutes and Epic Movie shouldn’t detract from the bright spots sprinkled throughout his resume. Had his breakout period from 2002 to 2004 lasted a little longer, he might’ve filled the “lumbering intensity” vacuum filled by an artist like Marco Beltrami.

Who Should Give Him a Call: Rodrigo Garcia, his frequent collaborator, has yet to do anything of note recently, so it would be great to see him tackle prestige television. Think in the vein of T Bone Burnett’s work on True Detective or Max Richter’s scoring for The Leftovers.

Best Introduction to the Composer: Though Reign of Fire is dark brilliance, his take on 2002’s The Count of Monte Cristo adaptation is a sweeping adventure score worthy of the all time greats.

[vsw id=”CkwISjJ_lQM” source=”youtube” width=”425″ height=”344″ autoplay=”no”]