Written by Kornél Mundruczó, Viktória Petrányi and Kata Wéber

Directed by Kornél Mundruczó

Hungary/Germany/Sweden, 2014

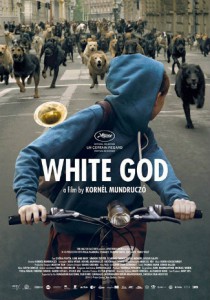

Kornél Mundruczó’s White God does for Budapest canines what Rise of the Planet of the Apes did for San Francisco simians. Instead of Caesar the ape, White God has Hagen the dog, who endures various means of suffering at the hands of human abusers before leading an animal uprising of his own. That plot point isn’t exactly a third act spoiler, as White God has an in medias res opening wherein Hagen and hundreds of dogs pelt through abandoned city streets, seemingly chasing a girl on a bicycle; the reveal is also the main image being used to advertise the film, so you might also draw a comparison to the Apes series there (“Statue of Liberty… that was our planet!”). It’s certainly an immediate attention-grabber, but it’s a ploy that undermines the power of that eventual climactic turn into ‘caninepocalypse’ mode. It’s not the only thing in the film undermined by the execution.

White God begins with a focus on humans. Thirteen-year-old Lili (Zsófia Psotta) is a child of divorce forced to stay with her estranged, uptight father, Dániel (Sándor Zsótér), when the mother she usually lives with must travel for a business trip. Lili brings along her trusted canine companion Hagen, but Daddy isn’t so keen on the doggy, particularly when its presence causes friction in his building; mixed-breeds like Hagen are a considerable target of disdain in the Budapest presented here. During a spat in a car with Lili, Dániel sets Hagen free on the streets and drives away. Lili later sets out to find her beloved dog and save him, but Hagen has already departed on his own incredible journey homeward bound (sorry) to find her. Along the way, this outcast dog becomes subject to various oppressive forces, from dog catchers to deceptively friendly hobos to criminals who force him to fight.

And so it goes that the plucky pup gradually becomes a battered brute, and then vicious avenger when he decides enough is enough, enlisting fellow canine outcasts in a mass assault on the human world that has mistreated them, be it random people on the street or specific bastards encountered en route to this psychological snap. It’s like if Au Hasard Balthazar suddenly turned into Death Wish. Or Straw Dogs. (Because dogs.)

White God goes down a more horror-oriented route than those films, however. Or at least it tries to, based on the tone you can ascertain from the individual scenes. Much of the film’s problems concern Mundruczó’s approach to its grisly revenge set-pieces and scenes of spectacle. The director has virtually no feel for horror in the scenes where he blatantly aims for actual scariness. These are mainly the moments where the human players who have done Hagen wrong earlier in the film are deliberately hunted down by either the lead dog alone or by a group of similarly bitey comrades. Each scene is a variant on someone investigating a noise in the shadows, only to be startled and mauled by Hagen and friends. Each one is delivered in the same flat manner with transgression-free gore (this is a film crying out for someone who can deliver a spectacular Grand Guignol climax), and each victim is a cartoonish stereotype; it’s appropriate that ‘straw dog’ also operates as a variant of the expression ‘straw man’.

The showiness of hundreds of (non-CG) dogs tearing down the streets has some undeniable power the first time you see it, but not so much when virtually the same set-up is shown on what’s practically a loop for the last forty minutes. And that explosion of animal fury doesn’t have a suitably cathartic release when, as mentioned, the film gives away the reveal as its opening gambit and subsequently makes the build-up to that uprising an all too predetermined outcome based around all too familiar misery porn. As Hagen, canine performers Body and Luke do a remarkable job, but Mundruczó, who also co-wrote the film, makes his hero nothing more than a blank-slate symbol for too heavy-handed mistreatment. And there really doesn’t seem to be much more to its allegorical underpinnings than that the abused and outcasts will have their day, a notion conveniently summed up almost word-for-word as a tagline on some English-language posters for the film.

Although the canine mayhem is chaotic, there needs to be some discernible sense to the political parable, but White God alternates between so many potential stand-ins that there’s no weight to any way you can read it. At various points, the dogs could represent immigrants, the poor, or… you know, animals that we should treat better in general. The allegory becomes even more incoherent in the film’s very last scene, which won’t be spoiled here, that sees a resolution to the drama that’s more in vein with a Disney fairytale its sneering human antagonists might feel right at home in than a work of any serious political bite.

A laborious, failed crossbreed of Amores Perros and The Birds, White God does at least have one enduring image beyond those plastered on its posters. It comes in the finale when Dániel brands a flamethrower in preparation to fend off the dogs outside. The reason the image endures? In this film, Sándor Zsótér as Dániel bears a particularly strong resemblance to American character actor Tom Noonan, perhaps best known as the Tooth Fairy killer in Manhunter. Tom Noonan, with a flamethrower, pitted against an unstoppable feral terror — someone with an actual knack for genre cinema make that movie, please.

— Josh Slater-Williams