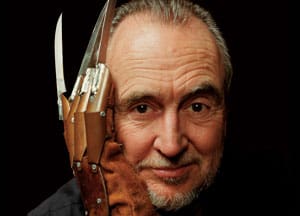

In 1984, Wes Craven made A Nightmare on Elm Street and gave a physical face to our childhood boogeymen. I was far too young to see the movie, but that didn’t matter. Freddy Krueger had stepped out of the film and become part of the cultural zeitgeist, sending a young boy’s imagination spinning in the middle of the night about all the ways he could come and get you.

It wouldn’t be until several years later when I would see a Nightmare on Elm Street movie, and it would ironically be the last one. In the middle of the ironic meta-movie fad created by Scream, I caught a late night showing of Wes Craven’s New Nightmare in which Craven plays himself writing the film we’re watching. It was not the experience I had expected. It wasn’t evil or harmful. It was clever, self-aware, thrilling… it was fun. It wasn’t until a second viewing when I became aware of Wes Craven. I popped in a VHS tape and recorded the film that was being shown on the drive-in movie late-night series TNT Monstervision with Joe Bob Briggs. Craven appears during the commercial breaks and discusses New Nightmare. This was a guy who didn’t just want to scare us, he wanted to challenge us to explore our own psyche. It was a revelation. With Craven’s invaluable comments, my little tape of New Nightmare pushed the 3-hour mark, and I held onto this special Director’s Commentary version until all things VHS had to go. Since then I’ve gobbled up as many of Craven’s movies and interviews as possible. It’s always been a joy to listen to Craven talk about film.

When Wes Craven passed away from brain cancer on August 30, it came as a shock because – and this may sound strange to say of a 76 year old man – he genuinely seemed to have a long career ahead of him. Few filmmakers reinvent themselves with the times the way Craven had. He reshaped The Virgin Spring to express frustration at the Vietnam War with the savage 1972 revenge film The Last House on the Left, he took on government cover-up paranoids through 1977’s The Hills Have Eyes, he took the silent slasher movie villain into the realm of the psychological in A Nightmare on Elm Street, and he pulled inside out the tropes of a genre that had grown tired in the ’90s, almost single-handedly defining meta-storytelling, with New Nightmare and Scream. Craven has some duds along the way (we’re going to pretend Vampire in Brooklyn doesn’t exist) but when he hit, he hit big. His hits spawned towering franchises, endless copycats and created subgenres like the Rape Revenge Film.

Craven was pushing toward 60 when Scream came along, a movie that was as hip and trendy with that generation of teenagers as Nightmare was a decade ago. While Craven usually wrote his own stuff, this story was written by Kevin Williamson of Dawson’s Creek fame. Their collaboration would extend to two more Scream sequels, and a quick look at the non-Williamson written Scream 3 or anything Williamson did without Craven (like Teaching Mrs. Tingle) shows just how strongly these two brought out the best in each other.

The Scream series is surreal in how it allowed Craven a chance to reflect on a genre that he had such an influence on. The series frequently employs a Russian Nesting Doll narrative that comments on society, while commenting on itself. In Scream, we watch a screen on which a cameraman watches a screen on which Jamie Kennedy is watching a screen of Halloween. In Scream 2 Craven gets to take on “the effects of cinema violence on society” opening with a staggering intro that recreates the opening of Scream in the movie within the movie while another murder is taking place in the theater while we watch it in a theater. In what will end up being his final film, Scream 4, Craven takes on the industry’s pension for remakes, and in the movie’s best scene, Hayden Panettiere impressively rattles off a laundry list of every horror movie remake in the past few years, including remakes of Craven’s own movies The Last House on the Left, The Hills Have Eyes and Nightmare on Elm Street. It’s an appropriate final comment for “the quiet iconoclast” (as Clive Barker recently called Craven).

One of my favorite Craven quotes relates back to The Hills Have Eyes. He said the first monster the audience needs to be scared of is you (the filmmaker). They need to think “this guy is completely insane”. Horror movies seem to be the preferred genre of choice for the up and coming take-your-friends-into-the-woods-and-shoot-a-movie filmmaker because it can be pulled off cheap and easy. They’re all over Netflix, which makes the hunt for those diamonds in the rough so irresistible to horror fans. Your run of the mill indie horror filmmaker has their monster stab people because it looks cool and that’s how it’s always been done. Wes Craven has his monster stab people because it’s based on a psychosexual fear of being penetrated. Craven had thought through every inch of these movies. He always said he was exploring something bubbling inside him, an existential curiosity we all have about our own bodies and our own mortality. He said “people don’t like to be scared, they are scared”. The horror movie didn’t create fear, it released it (a metaphor played out in New Nightmare). Craven was brilliant in a way that I fear didn’t always translate through his movies, especially as they were dismissed as just horror. He articulately defended the genre as if it needed no defense. If only everyone got it as thoroughly as he did.

John Carpenter scared the hell out of me with Halloween, Alfred Hitchcock taught me the vulnerability of your main character with Psycho, but it was Wes Craven that taught me that horror movies could be intelligent, layered, psychological, socially conscious and fun.