Written by Miguel Gomes, Mariana Ricardo, and Telmo Churro

Directed by Miguel Gomes

Portugal, 2015

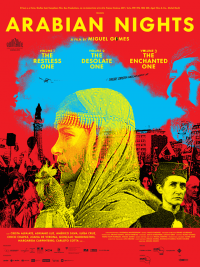

From a simplistic description, Miguel Gomes’s film Arabian Nights could sound unbearably self-important. Taking its name from a foundational collection of folk literature and running at a total of over six hours, the film almost sounds like a parody of arthouse excess. Add in the political goals of depicting life in contemporary Portugal under the pain of its economic collapse, and the mere concept of the film threatens to implode in self-seriousness.

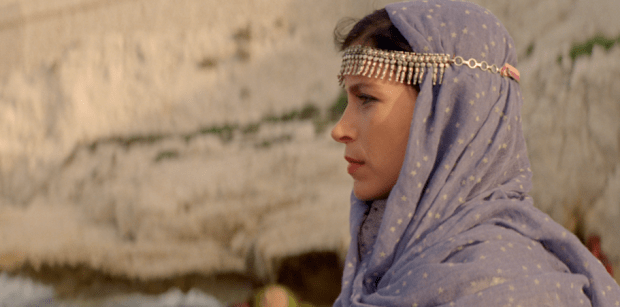

But in spite of this, the first segment of Arabian Nights (it’s being screened in three parts), subtitled The Restless One, maintains a whimsical tone throughout which quickly puts to rest any fears of pretentiousness. The film is funny, fast-moving, and too jocular to let accusations of self-importance stick. Not that Gomes doesn’t have serious ambitious for his project, none of which feel out of reach. More than anything else, he seems to want to represent the conditions of life in Portugal for a variety of Portuguese citizens, and the structure allows for a variety of stories to be told. As Arabian Nights explains through a cheeky and humorous title card, the film takes only the structure from its source material, using it to tell tales from a range of walks of Portuguese life. As with One Thousand and One Nights, the stories are told by a young woman named Scheherazade (Crista Alfaiate), but they’re the inventions of Gomes and co-writers Mariana Ricardo and Telmo Churro, inspired by real-life events occurring in Portugal between August 2013 and July 2014.

Before Scheherazade begins her tales, the film opens with a documentary-like half hour cutting between stories of shipyard workers being laid off, an apiarist fighting a vicious species of wasps, and Gomes struggling to figure out how to tell a story of Portuguese life. Although the segment seems disconnected from what follows, the message is clear: This is a film about people. In Gomes’s vision, no one’s story is too small to be insignificant, and everyone faces challenges worth documenting. It’s a powerfully democratic opening to a film, and one which hints at the range of Gomes’s focus.

His wide aim certainly still includes the more traditional stories of the rich and powerful, who are the subject of the first proper tale, titled “The Men With a Hard-On.” It depicts a troika meeting in which international lenders attempt to crack down on Portuguese debt, and the complications in their efforts from a wizard (Basirou Diallo), who grants the men with instant erections. The tale features a playful mix of real-life issues and sophomoric humor, with the jokes highlighting the absurdity of the Portuguese situation. The situation being represented is one which feels hard to believe, and the use of surrealism helps to highlight its bizarreness.

The same is true of the following segment, “The Story of the Cockerel and the Fire,” in which a rooster gets put on trial for being too loud too early in the morning. Meanwhile, three young children are engaged in a melodramatic love triangle, much of which is depicted through an impressive use of text message shorthand. The intersection (or lack thereof) of these situations is one of the film’s weakest elements, but they’re too entertaining to allow for too much of an objection. As with “The Men With a Hard-On,” the surrealism functions as a commentary of the surreal situation of modern-day Portugal.

Gomes uses surrealism least in the final segment, “The Swim of the Magnificents,” in which a trade unionist (Adriano Luz) speaks with unemployed citizens as he prepares and organizes a New Year’s Day swim. The story still features surreal elements such as an exploding beached whale and a mermaid, but these function tangentially to the story rather than serving as primary plot engines. They certainly don’t occlude the heart of the story, which lies in the tales of the workers and their struggles with the failing Portuguese economy.

Stories such as these are at the heart of Arabian Nights as a whole. The storytelling tradition the film draws from is a deeply humanistic one, and Gomes uses it for his explicitly humanistic aims. He’s telling the story of life in contemporary Portugal, even if representing that life means going beyond the realm of the real. Gomes does so frequently in The Restless One, but always with a light touch and in the name of capturing the feeling of being alive.

The 44th edition of the Festival du Nouveau Cinéma runs from October 7 to 18, 2015, in Montreal. Visit the festival’s official website for more information.