There are perhaps few filmmakers more contradictory and ultimately more fascinating than Abel Ferrara. The American director, most famous for crime dramas like Bad Lieutenant and King of New York, could be compared to an older auteur like Nicholas Ray who blurred lines not just between genres, but between art and industry. While Ferrara has often been forced to work outside both Hollywood and the United States in the past decade of his career, with many of his most recent films never receiving proper American releases, he’s often down to tackle studio assignments. Despite his acceptance of studio productions and interest in genre fiction, Ferrara is also fascinated by morality and corruption in a way that links him to European filmmakers like Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Pier Paolo Pasolini. In this sense, despite his films’ visceral and stark depictions of violence, sexuality, and substance use, he’s heavily informed by Catholicism, in an even more moral (and brutal) manner than Martin Scorsese.

For every film of Ferrara’s that is embraced by the festival circuit, there’s another reviled by the same audience. His work mires in the grit of Koch-era New York, from early exploitation features like The Driller Killer and Ms. 45 to 1987’s loose West Side Story retelling China Girl to his recent masterpiece Welcome to New York. However, he’s been an artistic outsider to the United States for years. Perhaps the closest cinematic figure I can compare him to is Jerry Lewis: ridiculed in America, beloved in France. His films are in constant conversation with one another; as pointed out in a piece by Otie Wheeler for MUBI Notebook, “King of New York, one of Ferrara’s best but most problematic pictures, was itself critiqued by [his later films] The Funeral and ‘R Xmas.” He is vocal about his opinions of other filmmakers, both in interviews and his movies; he garnered infamy at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival for disparaging comments about Palme D’Or-winning director Jane Campion, and his 2005 film Mary deals with the making of a film similar to The Passion of The Christ by a fictional director that resembles Mel Gibson. Ferrara may straddle dualities, but he’s never apologized for being who he is, whether as a person or a filmmaker. For better or for worse, that’s consistently placed him on the outside.

In a sense, this contradictory sensibility makes Ferrara a natural fit for a project like Body Snatchers, one of the finest films the director ever made for a major studio. Body Snatchers is the third adaptation of Jack Finney’s 1955 novel The Body Snatchers, from a screenplay by the team behind Re-Animator, Stuart Gordon and Dennis Paoli, and regular Ferrara collaborator Nicholas St. John. Unlike the two previous adaptations of Finney’s novel, Body Snatchers focuses on a young girl, Marti Malone, who moves with her family from military base to military base as her dad evaluates the chemical storage standards at each base. Unfortunately, despite being shown in competition at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival to mostly positive reviews, Body Snatchers was destined for obscurity. The film garnered a total domestic gross of $428,868, as Warner Brothers only released it to a handful of theaters.

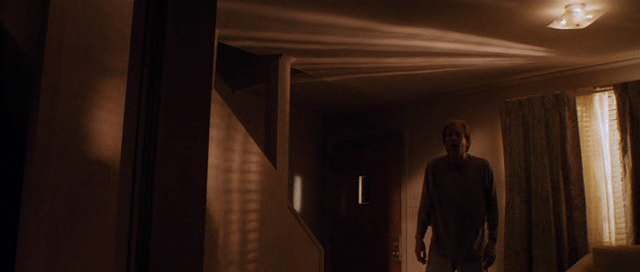

Many of Ferrara’s films focus on the evil of our world; while Body Snatchers does focus on evil from another world, it still zeroes in on the inherent darkness of our own. It’s also Ferrara’s only foray into science fiction and one of the few films he’s made that can be considered a strict horror film. However, he seems more interested in horror than he does in aliens. While Body Snatchers has its share of weak writing, Ferrara is both style-conscious and resourceful enough to work around these problems. He plays quite a bit with light- the shadows of soldiers standing menacingly on a ridge, white heat bursting into dark rooms. There’s an expressionist tilt to his take on alien invasion. It’s also an erotic film, as the body snatchings depicted on-screen are both disgusting on an organic level as well as deeply sexualized. It makes the idea of living in a body incapable of emotion seem illicit, even tantalizing. Body Snatchers may seem different than Alien or Lifeforce, but all three films share a similar sense of carnality.

The biggest change from the original source material and its two previous adaptations is a shift in location, as Ferrara translates the narrative to a military base in Alabama. This draws a natural comparison between the culture of the military and the community-above-all attitude of the pod people. As Roger Ebert noted in his 4-star review, Ferrara makes a connection “between the Army’s code of rigid conformity, and the behavior of the pod people, who seem like a logical extension of the same code.” But looking at Body Snatchers through this lens doesn’t allow for one to get beneath its surface; the film actually says more about family dynamics than it does about the American military.

When she was young, Marti’s mother passed away and her father remarried another woman, so there’s already an initial feeling that a central member of the family unit has been “replaced.” Marti’s stepmother is among the first on the military base to be “snatched” by the invading pod people, who plan to spread to other military bases across the United States, and it’s from there that the Malone family crumbles. The family unit is already under strain, as their constant moving causes Marti to rebel against her father. Unfortunately, the nature of the invasion triggers further familial conflict; Marti can’t tell if her father and brother have been snatched or not.

Body Snatchers ends with the suggestion that Marti will continue questioning the identity of everyone she meets, even after she escapes the danger. In some sense, it’s a truly transgressive film, as it questions the very nature of familial bonds. If our lives are in danger, should we stay with the people who look like us? Or do we even have any real connection to our families outside of genetics and marriage? While Marti finds a certain amount of solace in a new relationship with one of the soldiers on the base, their bond is only accelerated because of the invasion. Love doesn’t really exist between them; it’s just that they’re the only ones like each other left. That’s the true terror of Body Snatchers: living in a world where no one is like you, not even your family. In some ways, it’s a metaphor for Ferrara’s entire career on the outside. There’s never been a filmmaker like him, no matter how many comparisons we draw. Ferrara is only himself, and like the last line of dialogue in Body Snatchers says, “there’s no one like [him] left.”