Written by Richard Collins

Directed by Don Siegel

U.S.A., 1954

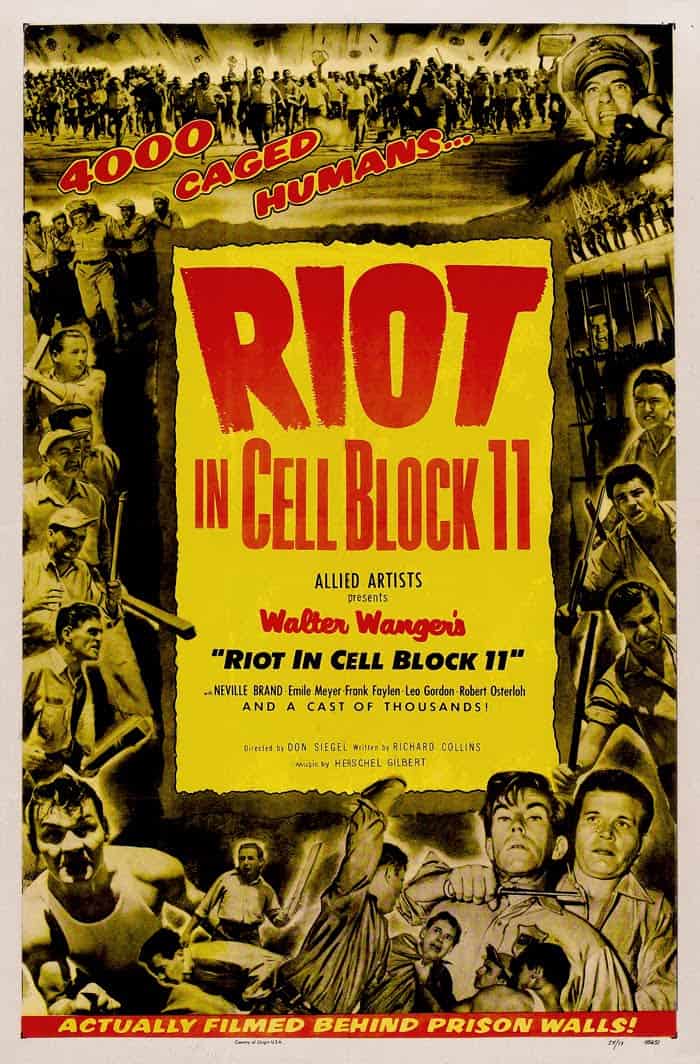

It is the dawn of great social change in the United States, a time when the public consciousness is about to reckon with real, humanity-based issues that plague the country underneath the veneer of perfection. A wave of riots have exploded in prisons across the country, alerting the media, politicians and ordinary citizens that the penitentiary system is deeply flawed. The prisoners are guilty of crimes, yes, but their confinement conditions go beyond the sort of punishment they should serve. Filmed on location at Folsom State Prison in California, Riot in Cell Block 11 concerns the inmate uprising led by James Dunn (Neville Brand), supported closely by a man nicknamed The Colonel (Robert Osterloh) and dangerous felon Mike Carnie (Leo Gordon) among others. The Warden, Reynolds (Emile Meyer), and Commissioner Haskell (Frank Faylen) have distinct philosophies as to how to take control of the situation, regularly clashing as the tension rises. Guards’ lives are at stake. The way politics are done is at stake. Careers are at stake. Power relations are at stake. Human decency is at stake!

If films like Dirty Harry and Riot in Cell Block 11 are any indication, director Don Siegel has bit of an anti-establishment streak in him. That said, his negative, or nuanced views on how institutions are run is in no shape or form a gut reaction against politics or power players just for the sake of it. His films, however realistic or intended to entertain through action, lean heavily on the principle that things can be done better. The world is not black and white but rather a more intellectually stimulating shade grey. Whereas Dirty Harry took a few shots at how the police force was run in the midst of a thrilling detective story, Riot in Cell Block 11 wears its social and political commentary much more visibly on its sleeve. Impressively, the film never loses focus of what any good piece of drama should accomplish, that being to tell a great story with memorable characters that the audience can appreciate and learn from, be they the heroes, the villains, or more complex mixtures of the two sides.

For starters, there is a bustling energy that ripples throughout the picture and never lets up until the very end, and even then the concluding scene, while relatively calm in its setting, clearly has extremely strong emotions boiling underneath the surface. The scene in which Dunn and his companions get the better of a handful of guards plays out very much like a prison break film would, yet these inmates have something entirely different on their minds. There is no grand scheme to flee or to destroy the building. The mission is more realistic and focused than that, a mission that, provided it bears fruit, will see that cell occupants will finally be the beneficiaries of a modicum of respect and humanity. Small spaces to live, low lighting conditions, the mingling of sane inmates and obvious psychopaths that puts far too many of them in danger, these demands are all sensible. What makes the situation so incredible is the party making said demands, hence why Riot is such a politically fascinating film to analyze. When a person is convicted of a crime and sent to ponder their actions in prison, how much of their humanity needs to be respected? What are the rights of a prison inmate, how much can he or she expect as far as treatment is concerned and how much is the public willing to listen to them? For that matter, how far are the public representatives willing to go to either protect the status quo or embrace change?

These volatile questions and their murky answers are organically covered as the drama reaches its peak and the tension along with it. Commissioner Haskell is unrepentant in his lack of interest in bargaining, making him the most cookie cutter of the characters in film, but the rest of the individuals concerned all have multiple layers that make their positions and standings in the eyes of the viewer either especially precarious or less clear cut than originally foreseen. James Dunn is played wonderfully by Neville Brand, an actor who appeared regularly in films noir of the era in supporting roles, but gets star billing here as the leader of the revolt. He is such a fascinating character because of his deep belief in wanting to improve the conditions of his fellow inmates, yet occasionally gives in to the lesser enviable instincts that assumingly landed him in the slammer in the first place. He can be a villain, in fact he is a villain (the movie makes this clear in a couple of instances) but his cause is, ultimately, just. The Colonel, the most level-headed of the bunch, is played with deliberate caution and skill by Robert Osterloh. He agrees with the demands but feels discomfort regarding the riot itself, not to mention that he has the opportunity to go on parole soon enough, causing him to restrict his own involvement to a degree for very selfish reasons. Emile Meyer is a strong, principled presence as Warden Reynolds, the counterpart to Commissioner Haskell. He has been vocalizing very much the same demands as Dunn’s group for years, yet he also expresses some reservations about how to negotiate the terms seeing as some of his own guards are threatening to be executed. It would be quite the turn of events if the claims he has battled for within the system are met via a dangerous, violent prisoner revolt.

The importance the film gives the situation is not only a product of the realities of the U.S. prison system at the time and director Don Siegel’s personal inclinations, but also that of producer Walter Wanger, who himself had spent four months in a penitentiary for shooting his wife’s lover, witnessing first hand the paltry conditions under which inmates wasted away. The passion expressed about the topic is evident from the film’s first frame, and the best part is that the filmmakers successfully juggle the picture’s ambiguous politics with rousing tension. There are a handful of scenes in which the seething rage, expressed on both sides of the debate, is on full display. In one of Riot’s best sequences, the state police are brought in to control a second cell block that has begun its own revolt of sorts. The prisoners, presently outside in the yard, are lured back into their block by the policemen firing their rifles towards the ground. Palpable tension dominates the moments, as the disgruntled inmates snarl and taunt the officers, who in return do their best to not get too trigger happy…until one young policeman gives in to his own disdain for the opposition and shoots a prisoner dead, further complicating the negotiations between Dunn and Reynolds.

Riot in Cell Block 11 is a stellar film, replete with passionate debate, fully fledged characters with sensible opinions that differ greatly, and, most critically, is a tremendous thriller set in and around the confines of a prison ready to explode in frustration. Don Siegel’s filmography is demonstrative of his range and class as a director, with Rio in Cell Block 11 being one of his most gut wrenching pictures.

-Edgar Chaput