Collects The Wicked + the Divine #12-17

Story by Kieron Gillen

Art by Jamie McKelvie, Kate Brown, Tula Lotay, Stephanie Hans, Brandon Graham, and Leila Del Duca

Colors by Matthew Wilson, Kate Brown, Tula Lotay, Stephanie Hans, Brandon Graham, and Mat Lopes

Letters by Clayton Cowles

Published: February 3, 2016 by Image Comics

The Wicked + The Divine Vol. 3: Commerical Suicide develops many of the still mysterious Pantheon members, presents a subset of the responses to the deaths of the first two volumes, and progresses the story toward Ananke’s predicted war between the sky gods and the gods of the underworld. Each issue focuses on a different Pantheon member and is illustrated by a different guest artist, brilliantly highlighting the different personalities and music genres of each focus god. Together the volume delves into the dark side of fame and power as the Pantheon tries to keep from falling apart.

The end of volume two left the narrative in lurch. Reader analogue Laura was deified and then murdered. Who would be the new guide through the coming issues? The reader is left a bit lost heading into Commercial Suicide, a parallel to the pantheon gods still reeling from Inanna’s death. Baal is the first to escalate the situation, but not the last, trading an exclusive interview for the opportunity to capture the Morrigan and use her to find Baphomet, upon whom he intends to inflict a violent retribution. His act, however, splinters the group. Meanwhile, others deal with internal conflict. Woden questions his allegiance to Ananke and acts to block her next murderous move while also attempting to keep loose canons like Baal and Sakhmet from publicly committing commercial suicide.

It’s one thing to grab the attention of the masses; it’s another to keep it from turning on you. Tara’s narrative especially explores this, as she attempts to emotionally deal with questions of identity, meaning, and fan backlash. Not knowing which Tara goddess she’s the incarnation of, she lacks an understanding of her greater self. Sakhmet, on the other hand, understands exactly who she is–a cool cat who does exactly as she pleases. Her god is built on the idea of not caring. She will eat you. Tara, however, feels her body is up for consumption, there for what pleases others. This is the celebrity paradox–the celebrity is all powerful, fame and fortune at their disposal, feeding on the adoration and pocketbooks of fans; the celebrity is there only for the fans’ pleasure and thus at their collective mercy. Tara feels entirely dehumanized by her godhood–she is both dismissed and idolized.

Amaterasu likewise grapples with her godhood. She is a Fan. She is a Fanatic. The kind that does fanart reblogged on Tumblr. Her creative juices have always been appropriative, at first with video games, and now with gods. She and Cassandra (Urdr) re-enact arguably the most tragic of moments in Japanese history in a philosophical dispute that boils down to whether everything happens for a reason or nothing does. Cassandra may have the best line in the volume with, “Who do you think we are? The Culturally Appropriative Avengers?” Of course, each issue that explores character backstory–Amaterasu, Tara, Sakhmet, the Morrigan–show that these women were picked by Ananke for a reason. But that reason is a mystery. Amaterasu’s positivism equates to the series tagline: “Don’t worry. It’s going to be okay.” But, to be honest, we all have our doubts. Cassandra is the voice of those doubts through her unmerciful deconstruction of Amaterau’s illusions.

All of this sets up impending war within the pantheon. Ananke gives voice to wanting to stop it, but her actions suggest the opposite. What does she have to gain from the pantheon consuming itself? Is there another key player yet to be introduced? A repeated motif in issues 14-17 is the roles and absence of fathers. Ananke is a mother to the Pantheon, but perhaps there is a father out there too, one that Ananke is attempting to goad into the public eye.

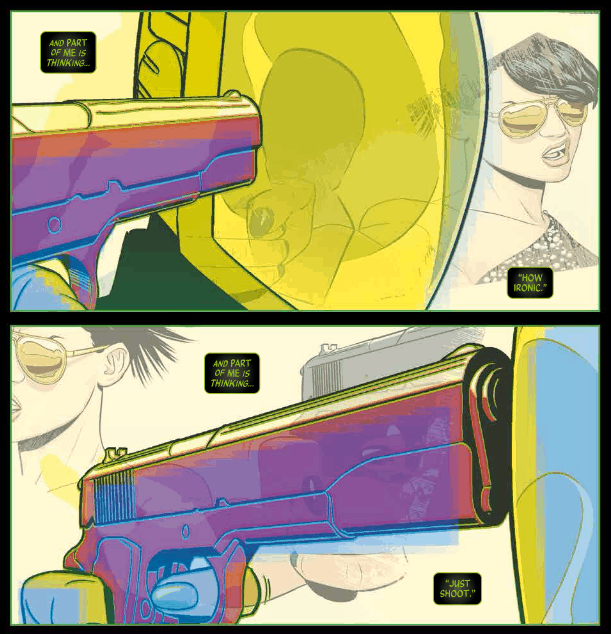

Jamie McKelvie, the series’ regular artist, has always felt like the perfect match for the style and substance of Kieron Gillen’s characters. So initially the switches from guest artist to guest artist feel jarring. Aptly so, as the changes highlight the pantheon’s fracturing due to conflicts among the larger-than-life personalities and the possibly nefarious machinations of Ananke. Each artist adds a new vision of the gods, a new understanding, and a new emotional tonality. These issues dig deeply into the psyches of the individual gods, and each artist embraces the gods’ psychologies in the visuals. Highlights include Tula Lotay’s gut-wrenching portrayal of hate mobs, rape culture, and self-blame in Tara’s spotlight issue, Stephanie Hans’ gorgeous play of light against dark in the stand-off between Amaterasu and the Norns, and Brandon Graham’s humor-tinged, loose-lined, cat-cartoony portrayal of Sakhmet.

McKelvie’s art is still exquisitely displayed on the covers, in the backmatter called “Videogames,” and in the experimental masterpiece that is Woden’s issue #14. Woden, loosely based on Daft Punk, tells his story in re-mix. The visuals are reformatted, combined, and colored from previous issues in the way that DJ’s recombine samples from music to create something a new track. Woden offers a particularly interesting take on the events of past issues due to his proximity to Ananke.

Fans of the series should not miss Commerical Suicide, which gives deep character insight and thematic development to the questions of identity, personal and public, through disparate experiences and art that solidify the similarities inside celebrity and fan alike.