Few national film industries have ever been able to rival Hollywood, whose output dominates the global film market. But for several decades, Hong Kong’s cinema provided stiff competition, regularly beating American movies at their local box office. But as the years went on, directors and stars from Hong Kong wanted something more and started knocking on Hollywood’s door. After changing the game with the vivid stylings of 1986’s A Better Tomorrow, director John Woo set his sights on the American market, producing a string of legendary action films (The Killer, Hard Boiled) that found an audience in the United States through arthouse theaters and home video. Despite the international cult status of Woo’s work, these films didn’t do so well at the Hong Kong box office. But that didn’t matter to Woo; these movies were his international calling cards. After formally introducing himself to American audiences with 1993’s Hard Target, Woo became a dependable studio journeyman in the United States for almost a decade.

American studios loved Woo, so much so that they looked for more talent in Hong Kong, bringing directors like Tsui Hark and Ringo Lam to America. Soon Hollywood directors picked up on this new style, in the same way that their Hong Kong counterparts took cues from movies like Top Gun and Lethal Weapon in the 1980s. As pointed out by David Bordwell in his essential book Planet Hong Kong, American action films underwent a “Hong Kongification” in the late 90s, signaled by films like Michael Bay’s Bad Boys, Simon West’s Con Air, and Antoine Fuqua’s The Replacement Killers; these movies were brasher, bolder, and bigger than anything that had come before.

This is all to say that, for better or worse, Hong Kong action cinema irrevocably altered the shape and style of Hollywood blockbuster filmmaking. But Hong Kong’s most famous contribution to American pop culture comes not from its directors, but one of its stars: Jackie Chan. If, like me, you grew up in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it’s hard to believe that Chan hadn’t always worked in the United States, as he was an almost constant fixture in the pop culture universe of my childhood. After a decade of Belgian beefcake and Austrian Adonises, Jackie Chan was exactly what America audiences needed: an action hero you felt comfortable taking home to mom and dad. He’s as lovable as he is lethal, as good with kids as he is with kung fu.

Although Chan actually got his start as a child actor, his career didn’t take off until the late 1970s. After Bruce Lee’s death, Jackie’s long-time manager Willie Chan attempted to sell him as the next Lee; although Jackie had worked as a stuntman on Fist of Fury and Enter the Dragon, he couldn’t quite get the hang of Lee’s style and soon drifted to more comedic roles. The success of 1978’s Drunken Master, which exemplifies his marriage of high-flying, acrobatic kung fu and slapstick comedy, finally propelled Jackie to stardom in Hong Kong. After an unsuccessful attempt to break into the American market with films like The Big Brawl and The Protector in the early 1980s, Jackie returned to Hong Kong and produced some of his most famous films, including Police Story and Wheels on Meals. Chan finally broke through to American audiences with Rumble in the Bronx, which hit theaters in the United States twenty years ago this month.

Bronx exemplifies what American audiences came to love and expect from Jackie Chan. He plays Keung, a Hong Kong cop visiting New York for the wedding of his uncle. While the United States seems at first like an accepting land of opportunity, Keung soon finds that it’s actually the opposite. He means well, but lands in the middle of a criminal conspiracy and ends up doing battle with a roving gang of goons who look like extras from The Warriors. Keung’s an endearing everyman, a perpetual underdog with a penchant for making enemies even when he means well. He’s dorky but dangerous, a chivalrous outsider who dresses a little like Jerry Seinfeld and maintains a clear sense of right and wrong.

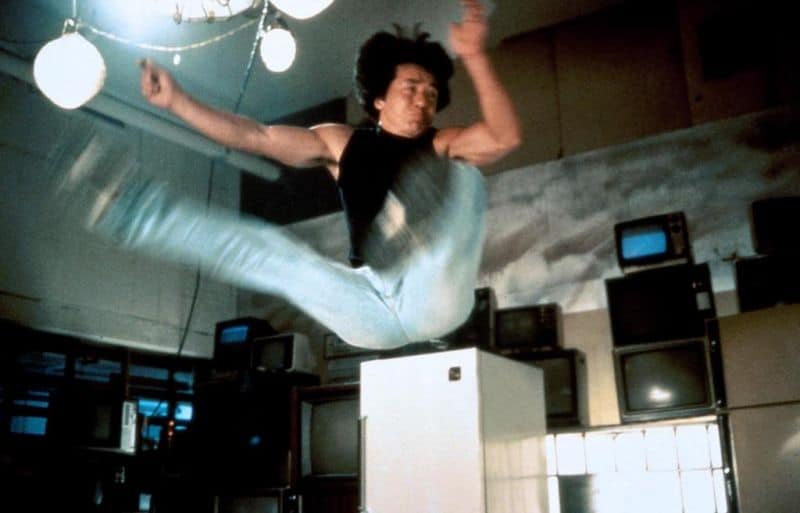

Chan’s style of fighting reflects his stock character; it’s less about the weight behind his blows and more about the speed and precision with which he delivers them. He’s a whirling dervish. Martial arts aside, it makes sense that Chan couldn’t capture Lee’s style. Bruce Lee was a little like a Hong Kong James Dean, a wild bolt of pure intensity who died as fast as he lived. Jackie Chan is a little more like Jerry Lewis, and has always seemed more interested in comedy than pure kung fu.

Chan is well known for his worship of silent stars like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd, and like his heroes, he’s also famous for the extreme risks he takes to land a gag, often resulting in accident and injury. Even though Chan’s character is a little more graceful on his feet than those played by his inspirations, he still doesn’t win every fight. His character might be a master of martial arts, but he’s new in town, which means he never has total control over his physical environment. Chan’s about the farthest thing from, say, Riki-Oh; it’s the physical abuse he puts up with that makes us root for him. He’s not just an action hero, he’s a vaudevillian, which means pain is just as central to his persona as physical prowess.

Though the ridiculousness of Rumble in the Bronx roots it firmly in the tradition of Hong Kong action cinema, it signaled the arrival of a bright new star in the American popular cinema. He might have failed the first time, but Jackie Chan struck it big in the United States on his second go-round, raking in cash and earning audience adoration with hits like Rush Hour and Shanghai Knights. His presence in American pop culture might have lessened in his elder years, but he remains one of the most important and endearing figures in global action cinema.