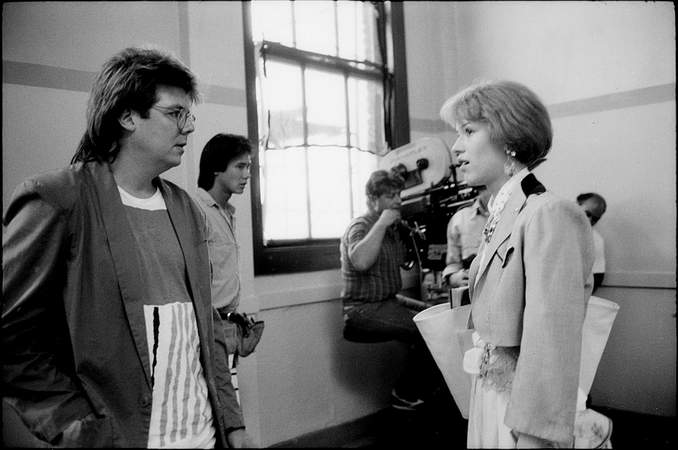

Hughes had long been inspired by Ringwald after seeing her photo in a casting lineup, writing Andie’s role with her in mind (as well as her roles in 1984’s Sixteen Candles and 1985’s The Breakfast Club) and hoping to cast her in future films like Some Kind of Wonderful. But a quick look at the movie’s credits reveals something unique about this film so closely tied to its writer. Namely, that Hughes did not direct it, relegating those duties to his then-protege and first-time director Howard Deutch.

Although perhaps just a move to allow Hughes more time to write and Deutch to gain more experience directing, interviews with Ringwald suggest that she and Hughes may have suffered an unspoken falling out after expressing a desire to branch into other types of projects post-Pretty in Pink. In fact, they never worked together again. Hughes’ other muse and Ringwald’s one-time boyfriend, Anthony Michael Hall, also expressed similar confusion about the director’s sudden distance, wondering if Hughes had simply become dissatisfied that Hall and Ringwald had “veered off script” to live a life outside of his narratives. Whatever the case, the emotional pitfalls only increased behind the scenes.

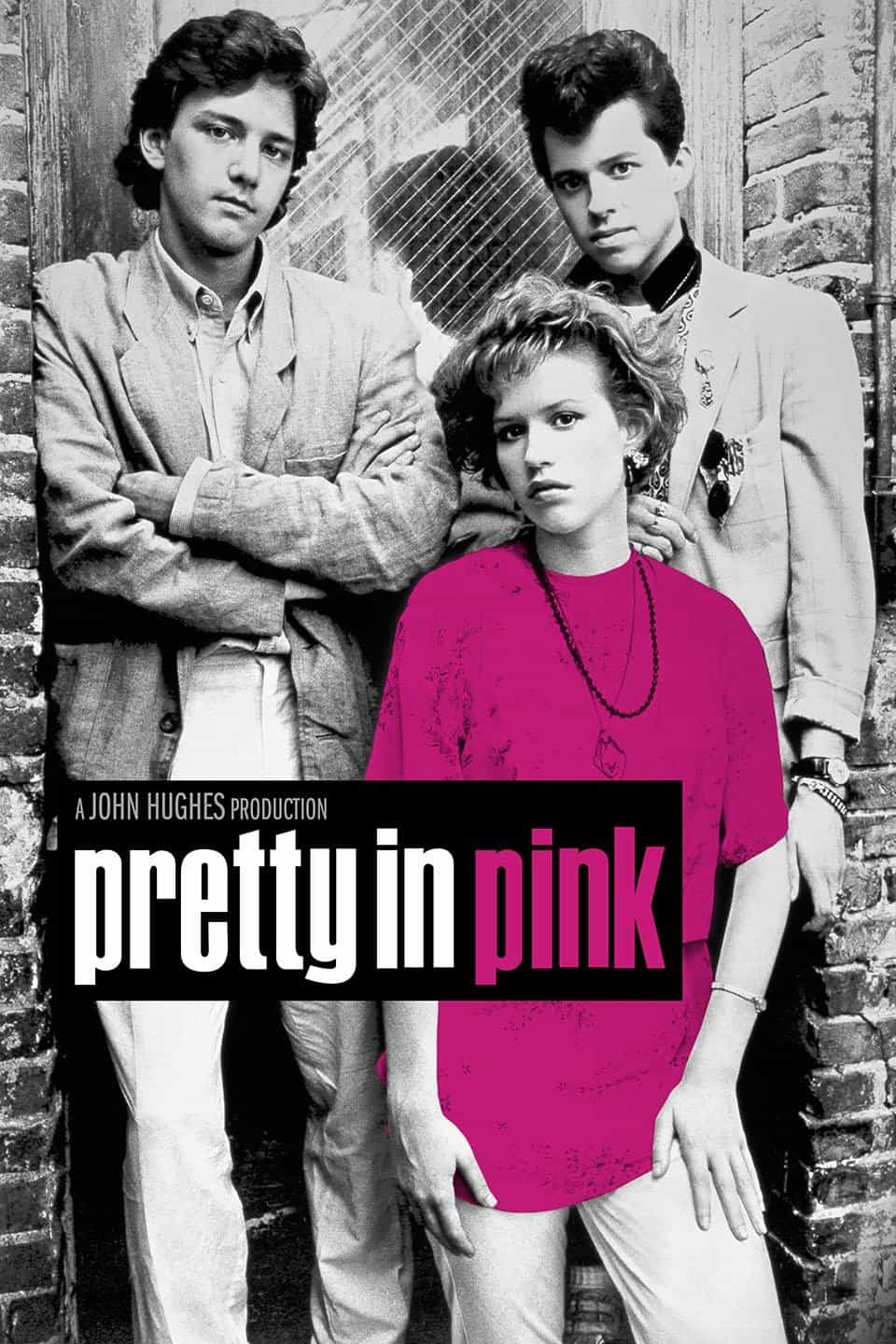

The film follows many of Hughes’ traditional beats. Molly Ringwald plays Andie Walsh, a serious girl from the wrong side of the tracks who challenges the status quo when she enters into a relationship with the wealthy Blane, played by Andrew McCarthy. A veil of hopelessness prevails—her mother has abandoned the family, her father’s lack of work forces her to supplement his income, and her wacky best friend Duckie, played by John Cryer, pines for her unrequited attention. A falling out ensues between all involved, relationships are tested, but the lines that separate each character supposedly fade away into a happy ending.

But in contrast to other Hughes-penned films like Sixteen Candles or The Breakfast Club, Pretty in Pink garnered a significant amount of critical fame for aspects of its narrative that just didn’t seem to work. In its initial test screening, everything appeared to be going well for Hughes’ next foray until, with only five minutes left, something unanticipated happened. The audience booed, upset that Andie ultimately ends up with Duckie, not Blane, at the school prom. If that ending sounds unfamiliar to anyone not present at the test screening, that’s because it never made the final cut. Deutch and Hughes were eventually persuaded by the studio to reshoot the scene so that Andie chooses Blane instead, an implied victory for cross-status romance, but a decision Deutch says still bothers him to this day.

“Politics aside, they were like, ‘We want her to get the cute boy.’ And that was it,” Deutch said in a 2014 interview with Vulture.

That Deutch—or perhaps the original test screen audience—uses “cute boy” to describe Blane and not Duckie also has its roots in the complexity of Cryer’s casting, at least in terms of his ability to get the girl in the original ending. After landing the part by amusing Deutch with an impression of Mick Jagger’s “Start Me Up”—later reworked into the film’s iconic “Try a Little Tenderness” scene—Cryer’s performance stands out as the comedic core of the film, ad-libbing a few of the film’s most memorable lines. But despite bringing to life one of the most eccentric characters in the Hughesian repertoire, the lanky and pompadoured Cryer wasn’t exactly Ringwald’s first choice for the supporting role.

“Actually,” says Ringwald in Susannah Gora’s book, You Couldn’t Ignore Me if You Tried: The Brat Pack, John Hughes, and Their Impact on a Generation, “I think he seemed gay. I mean, if they remade the movie now, he would be, like, the gay friend who comes out at the end. He wouldn’t be winking at a blonde [Kristy Swanson], he would be winking at a cute guy.”

Instead, Ringwald had a different member of the Brat Pack in mind.

“I feel bad saying that I really fought for Robert Downey, Jr.,” she says, “because it sort of seems like I don’t appreciate Jon’s performance, which I totally do — it’s just, it really did affect the movie.”

In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Cryer, who had known Downey since they attended the same summer camp as kids, admits to feeling disappointed with the decision to reshoot the film’s ending.

“But I think it was kind of appropriate,” he adds. “Duckie always thought he was the leading man, and that was his fatal flaw.” In other words, it was Duckie’s nature, not his status, that hindered his romantic goals.

“You’re not one to face things,” Andie tells Duckie during an argument, and if Duckie’s frantic enthusiasm serve as any evidence, then Andie is right. Alone in his room as Andie goes on a date with Blane, Duckie sits on a dirty mattress listening to “Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want” by The Smiths, backdropped by a furniture-less room and crudely-drawn images on the wall. When Duckie expresses frustration that “they just don’t write love songs like they used to,” his words could be translated as his frustration that a traditional, happily-ever-after narrative like Andie’s will never be his to have.

Whether or not Hughes intended to turn Duckie into the film’s tragic hero, even Roger Ebert in his 1986 review sided with the new ending, writing that Andie and Blane were “obviously intended for one another.” Plus, as Cryer’s previous quote suggests, an ending without their reconciliation may have accidentally worked against one of Pretty in Pink’s intended themes—crossing social and economic boundaries in the name of love.

Gora records Cryer’s opinion in her book:

“I was a little hurt,” he says, “because you feel it reflects on you as an actor, because you didn’t get the audience to invest enough in [Andie and Duckie’s] relationships in such a way that it would be satisfying that they would end up together. But at the same time,” he points out, “I got it. The whole movie seems to be about trying to bridge that divide,” the divide between cool kids and nerds, between the Blanes of the world and the Andies, between rich and poor. “You can’t give people the impression that it can’t be bridged,” says Cryer, earnestly. “You can’t send a message that interclass romance just can’t possibly work.”

To forgive themselves for sacrificing Duckie for Andie’s sake, Hughes and Deutch rectified their dissatisfaction with Pretty in Pink in 1987’s Some Kind of Wonderful, in which Eric Stoltz’s Keith and Mary Stewart Masterson’s Watts—two working class misfits who essentially fill the rolls of Andie and Duckie, respectively—do end up in love despite the presence of popular, rich, but still amiable Amanda. In fact, the successive timing of the film’s release even prompted Janis Maslin of The New York Times to call the film “a much-improved, recycled version of the ‘Pretty in Pink’ story.”

Still, when compared to the lexicon of Hughes’ films, Pretty in Pink remains a powerhouse depiction of teenaged life rarely seen on modern television. With one of the greatest movie soundtracks of all time (the misinterpretation of The Psychedelic Furs’ “Pretty in Pink” aside), stirring performances, and a storyline that has remained conversational for 30 years, the film has stood the test of time. Although perhaps one of the most imperfect of Hughes’ creations, its charms make up for its shortcomings, admirable in its intention to present a world in which people find love and friendship in spite of pain.

So Andie may not have been in love with Duckie. But as one of her final lines at the prom suggests, that doesn’t mean she didn’t care.

“May I admire you?” she asks her steadfast friend, an echo of one of Duckie’s lines from earlier and the question modern audiences still pose to the film thirty years later. And the answer, in all its imperfection, is yes.