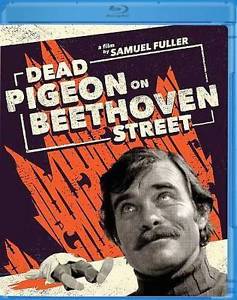

Written and directed by Samuel Fuller

Germany, 1973

Sam Fuller was having a rough go of it by the early 1970s. The success of his bombastic B-movie masterpieces Shock Corridor (1963) and The Naked Kiss (1964) had dwindled, his Burt Reynolds-starring Shark! (1969) was an obstructed critical and commercial disaster, and as American cinema underwent a resounding transitional phase, Fuller the iconoclastic director faced repeated difficulties in seeing new projects realized. Ironically, while he struggled to get a string of features off the ground, his popularity was nevertheless growing, especially in Europe, and his prior work was in the midst of a pronounced reevaluation.

It was within this career context that Fuller was approached for his first international production. In California to interview directors from Hollywood’s golden age, German filmmaker Hans-Christoph Blumenberg met with Fuller and the two hit it off. Before their session of wine, food, and conversation was complete, a new venture had been proposed. Fuller was set to write and direct an episode of the tremendously popular and extremely long running German television series Tatort (roughly translated as “scene of the crime”). His contribution was not to be an average segment, however (Fuller, for one thing, thought the series rather dreary). Shot on 35mm, Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street was always primed to be a theatrical feature that could stand apart from the rest of the series.

Inspired by the Profumo affair making English headlines at the time, Dead Pigeon picks up as American private investigator Sandy (Glenn Corbett) tracks down the negative of a compromising photograph showing a socialist United States senator in rapturous embrace with a less than reputable female figure. Behind the provocative picture is a syndicate of blackmailers enlisting high-class call girls to get wealthy statesmen in sticky situations. One of these enterprising young women is Christa (Christa Lang, Fuller’s wife), a seductive mystery woman and, to Sandy, the key to the extortion ring.

Inspired by the Profumo affair making English headlines at the time, Dead Pigeon picks up as American private investigator Sandy (Glenn Corbett) tracks down the negative of a compromising photograph showing a socialist United States senator in rapturous embrace with a less than reputable female figure. Behind the provocative picture is a syndicate of blackmailers enlisting high-class call girls to get wealthy statesmen in sticky situations. One of these enterprising young women is Christa (Christa Lang, Fuller’s wife), a seductive mystery woman and, to Sandy, the key to the extortion ring.

Passing himself off as a fellow blackmailer and potential competition, Sandy strikes up a manipulative relationship with Christa and the two partner. And what a Fuller partnership it is. “I like a careful bastard,” she tells him. “I like a bitch who can make up her mind,” he responds. As we watch the drama of their developing alliance, all the while knowing that he is working an angle just as she does on a regular basis, we can’t help but have some sympathy for them both. The question of who is playing who never fully dissipates, but such is the name of the game. In the meantime, though, they are a good team in business and a good pairing as a couple, even if there continually remains the pervasive likelihood of probable deceit.

Christa is a likeable femme fatale, especially when she showcases her efficiency and yet still expresses some guilt with certain victims, or seems to anyway. She likens her work to acting, and she’s not far off. She is essentially paid to put on an act and play a part. But this is exactly why one questions much of what she says and does. We know what Sandy is up to, but with her, we’re not so sure. For his part, Sandy is a smooth operator himself, slick and underhanded when he needs to be. Though ostensibly working on the side of law and order, he can be a shady fellow if that’s what the job calls for. Other times, he is clearly out of his element. He looks hopelessly lost and disheveled, a naive stranger in a strange land. Christa says he resembles an “unemployed rapist.”

Christa is a likeable femme fatale, especially when she showcases her efficiency and yet still expresses some guilt with certain victims, or seems to anyway. She likens her work to acting, and she’s not far off. She is essentially paid to put on an act and play a part. But this is exactly why one questions much of what she says and does. We know what Sandy is up to, but with her, we’re not so sure. For his part, Sandy is a smooth operator himself, slick and underhanded when he needs to be. Though ostensibly working on the side of law and order, he can be a shady fellow if that’s what the job calls for. Other times, he is clearly out of his element. He looks hopelessly lost and disheveled, a naive stranger in a strange land. Christa says he resembles an “unemployed rapist.”

Part of this sense of literal foreignness also stems from Sandy’s explicitly conveyed American identity. He is red, white, and blue to the core, so much so that he gushes over John Wayne to the point he nearly misses Christa as she attempts to evade his pursuit. Sandy is also an oddity in that he isn’t always a proficient hero. He is a very Sam Fuller type of protagonist, with faults in his abilities and his character. He is beaten up rather handily near the start of the film, which allows for his prime suspect to escape (“Wasn’t anybody there to give me a hand,” he complains), and at the end, in a rather comical duel, he is a generally inept opponent (though his resourcefulness leads to a brutally haphazard improvisation that nevertheless gets the job done).

To return to the very beginning of the film, in a credit sequence cut from certain existing prints of Dead Pigeon but restored for the new Olive Films Blu-ray, Fuller kicks things off with something of a sign of things to come, though it has little bearing on the actual plot until the ending of the picture. This enjoyably bizarre opening features most of the cast and crew (crew including the great cinematographer Jerzy Lipman, the assistant director, editor, and clapper man, among others), all adorned in clownish attire befitting their carnival situation. Fuller himself appears under his credit dressed in a multicolored jacket, sporting a pink hat, and chomping on his trademark cigar. Dead Pigeon may not maintain this degree of outlandish craziness at all times, but there is an atmosphere of “high jinks and hilarity,” as Fuller puts it, which remains throughout the movie. And as much as anything, this credit sequence also sets up the notion that those who were part of this film, a largely German production team, were evidently having a great time assuming their respective roles, something similarly conveyed in the exuberant, at times somewhat exaggerated, performances.

This is classic Fuller filmmaking, though, and as Dominik Graf notes, there is no mistaking the director’s “brand of ecstatic underground cinema.” Renowned film scholar Janet Bergstrom, who with Graf, Wim Wenders, Christa-Lang Fuller, Samantha Fuller, and others is interviewed as part of a fantastic, nearly two hour documentary on the making of the film (the Blu-ray’s standout supplement), argues Dead Pigeon is Fuller operating at the level of “pop art.” The opening that provides a behind the scenes glimpse of the filmmaking process itself is just the beginning of the movie’s artistic self-awareness. Emulating the French New Wave filmmakers who so admired him, Fuller includes in Dead Pigeon a variety of cinematic allusions, from Godard’s Alphaville (a clip that features Christa Lang alongside Eddie Constantine and Akim Tamiroff) to a German-dubbed Rio Bravo. The “audacious and Brechtian director’s cut” (in Samuel B. Prime’s words) is the only way to see this film that Fuller wanted to be both “funny” and “self-mocking.”

Sometimes it seems Fuller’s enthusiasm gets the better of him and the film’s overall construction can be a little choppy, as if it can barely contain itself. But the distinctly Fulleresque sequences that constitute Dead Pigeon make enough of the individual moments genuinely memorable even if the film as a whole might not add up. See, for example, an early scene at a hospital, which includes not only shots fired in a maternity ward, but a wheelchair bound patient being pushed down a staircase and Eric P. Caspar’s baddie Charlie Umlaut having his jaw cracked on each step as he makes his own rocky descent down the stairs. (Incidentally, Umlaut was a character Rainer Werner Fassbinder wanted to play, a casting decision Fuller nixed but later regretted.) Set to the rock-jazz music of Can, the film is a frenetic junction of “texture vs. story” (the name of a chapter in the aforementioned documentary), where the sights and sounds take precedence over a fully coherent narrative.

Sometimes it seems Fuller’s enthusiasm gets the better of him and the film’s overall construction can be a little choppy, as if it can barely contain itself. But the distinctly Fulleresque sequences that constitute Dead Pigeon make enough of the individual moments genuinely memorable even if the film as a whole might not add up. See, for example, an early scene at a hospital, which includes not only shots fired in a maternity ward, but a wheelchair bound patient being pushed down a staircase and Eric P. Caspar’s baddie Charlie Umlaut having his jaw cracked on each step as he makes his own rocky descent down the stairs. (Incidentally, Umlaut was a character Rainer Werner Fassbinder wanted to play, a casting decision Fuller nixed but later regretted.) Set to the rock-jazz music of Can, the film is a frenetic junction of “texture vs. story” (the name of a chapter in the aforementioned documentary), where the sights and sounds take precedence over a fully coherent narrative.

Dead Pigeon also marked Fuller’s conflicted return to Germany, his first visit to the region since he was stationed there as a combatant during World War II. Looking at the country with a new perspective, Fuller cinematically surveys the cities of Cologne, Munich, and Bonn with an admiring, touristic sense of exploration. His fascination with the West German locations was so evident during filmmaking that he would craft entire scenes around particular settings (Beethoven’s birth house, for example, a site where Fuller once spent the night as a soldier in the famed Big Red One unit).

Though Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street was generally well-received, Fuller’s career didn’t fare much better as a result. Further television work rounded out the 1970s, and in 1980, he was finally able to direct the long-gestating The Big Red One, his autobiographical passion project. But even that suffered under the weight of outside interference, as would his following film, White Dog (1982). For a brief time in Germany, though, Sam Fuller was operating just as he liked, with autonomy and enthusiasm. “Hell, Dead Pigeon wasn’t my most accomplished movie,” he acknowledged, “but it was an accomplishment for me to have made it in Europe instead of in my own country.”