Welcome to our detailed series outlining and reviewing our favorite Darren Aronofsky movies.

π

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Darren Aronofsky

Starring Sean Gullete, Mark Margolis, Ben Shenkman

1998, USA

At the London press conference for his new film Black Swan director Darren Aronofsky was asked what advice he would give to budding film-makers, ‘Make something different’ he opined, ‘do anything to stand out from the crowd and get yourself noticed’. It’s a credo culled from his own experience, as his debut feature Pi stormed the 1998 Sundance Film Festival, capturing the award for best direction and heralding the arrival of an anxious new talent in American cinema. Shot on high contrast black and white stock, the film is the story of Max Cohen (Sean Gullete), a genius mathematician loner whose human contact is limited to a sultry female neighbour and his elderly mentor in the field of algebraic abstraction, Sol Robson ,who is portrayed by a brusque Mark Margolis.

Suffering from a plethora of anxieties and ailments – headaches, paranoia, social anxiety, nosebleeds – Max suffers under the misapprehension that everything in the universe can be processed through numbers, that tangible frameworks such as the stock market and the fractal geometries inherent in nature can be predicted, manipulated and controlled. Max meets a hasidic Jew, Lenny, who explains to him that their are theories that when the Torah is translated through a process of Gematria, of matching the Hebrew alphabet to numbers, that the voice of god becomes apparent in logometric form. A mysterious woman, Marcy Dawson, introduces herself to Max and compels him to work for her in predicting stock market fluctuations in return for a supercomputer chip, the Ming Mecha, a device that will accelerate his electronic research on his bespoke computer system named Eucilid. The extent to which these figures are phantoms in Max’s distressed mind is kept ambiguous but as the threats colaesce his sanity deteriorates, prompting a dangerous solution to his manic condition.

Pi is a delirious film that signals the major theme that dominates Aronofsky’s cinema: an obsession with obsession, and the consequences of those compulsions on the mental and physical lives of his protagonists. Its lucid and frenetic editing denotes a break from hysteria to calm, and encapsulate Max’s obsessive compulsive disorder, while the bleached whites and glassy blacks complement the electronica purr of Clint Mansell’s score. It’s a film that photographs a pre-millenial anxiety, when chaos theory was a talking point in every stoned student dormitory, when the Kabbalah was a new and attractive religious affectation, and the millennium bug threatened to grind western civilisation to an anarchic halt. Judged from the perspective of a decade into a new century the project might seem a little too Dan Brown for hipsters, but as Aronofsky remarks on the commentary that Pi was a film about seeking answers in the maelstrom, about the search for order amongst the turbulence, rather than providing any concrete answers. Reminiscent of both Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man and David Lynch’s malignant Eraserhead, Pi encapsulates the divination of the peripheral and the thin barricade between genius and insanity, its smouldering neurosis like the recent Coen film A Serious Man, suggesting an ideal double-bill on the fractured search for knowledge and reason behind the anarchy of the universe.

-John McEntee

Requiem for a Dream

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Hubert Selby Jr.

2000, USA

The apotheosis of ADD. MTV-era filmmaking, Requiem for a Dream is designed to divide. Its mathematically precise editing and histrionic message-driving makes it perhaps the shrillest anti-drug movie of any age, yet its hyperbolic sense of terror and frenetic rhythms manage not to obscure its less obvious gifts. It announces its creator as a force to be reckoned with, even if some will rightly take issue with the film’s combustible content.

Presenting the addict’s progression as a seasonal process, Requiem is divided into “Spring,” “Summer,” “Fall,” and “Winter,” with each segment more perilous than the last. Our victims are young, handsome Harry Goldfarb (Jared Leto); his jittery mother Sara (a devastating Ellen Burstyn); his best friend Tyrone (Marlon Wayans in a rare dramatic role) and his loving girlfriend Marion (Jennifer Connelly). Harry and Tyrone are small-time hoods with a taste for heroin, itching to get a line on becoming sellers, Marion is collateral damage, and Sara is privately developing an extreme dependence on “uppers” (speed) after being led to believe she is to appear on her favorite TV show, a vacuous serial infomercial hosted by an odious shill (Christopher MacDonald).

Requiem has only one mode (hyperactive) and only one direction (down). Even in scenes where characters aren’t doping themselves up, splitscreen is frequently invoked, along with garish lighting and dialogue that foreshadows doom with the subtlety of Alice Cooper’s wardrobe. Clint Mansell’s iconic score, performed with the Kronos Quartet, elaborates and contorts a couple of memorable themes into increasingly desperate shapes. All four leads are cast to engender maximum audience empathy, and thereby inflict maximum emotional damage when they collapse into the film’s climactic montage, an extended nightmare involving electro-shock therapy, invasive surgery, and a party favor that must surely count as one of the nastiest visions in movie history.

Yet, for its shameless machinations, it’s impossible to deny that Requiem possesses a rare power and vitality. Aronofsky tends to coax out great performances, and Burstyn in particular astonishes, with the help of excellent technical work that effectively transforms her from a paragon of positive thinking to something scarcely resembling a person. Even as he nicks a shot from Perfect Blue, subdivides the screen into eternity, and yanks on every possible heartstring, Aronofsky (and by extension, collaborator Mansell, whose role in tying the film together cannot be overstated) prove, if only through blunt force, that he can go toe-to-toe with any current filmmaker in terms of ambition and technical prowess.

– Simon Howell

The Fountain

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Darren Aronofsky

2010, USA

In many ways, The Fountain is possibly the greatest comic book adaptation of all time. First attempted in 2002, with Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett attached and a 75 million dollar budget, Aronofsky’s eventual follow up to the very personal and incredibly bleak Requiem for a Dream was a space- and time -panning epic that collapsed when Brad Pitt quit to go make Troy. Incredibly the entire Australian production was shut down and props auctioned off. Frustrated, Aronofsky found some solace in adapting his masterpiece into a graphic novel (gorgeously illustrated by Kent Williams) which remains to this day the only true representation of his original vision.

Determined to find a way to still create a filmic version ,he rewrote the screenplay,exploiting his resourcefulness to hack the budget in half and refine the scale to create a more intimate and humble narrative that would still retain the magical epic gravitas of his basic ideas. Production eventually began on this new version two years later, and it was finally released in 2006 to critical acclaim but public confusion.

The Fountain is a flawed masterpiece. Its story spans three timelines; a conquistador travelling to New Spain to hunt for the tree of life to free his shackled country and Queen, a scientist in modern times desperately trying to find a cure for his dying wife, and a traveler of space at some undisclosed time in the future, racing toward a dying nebula in the hope of being re-united with his wife in its rebirth.

It would be easy to label The Fountain as either confused or pretentious. It is edited in a very non-linear fashion, it’s difficult to truly distinguish that which is actually happening, that which is merely a visual metaphor and that which is part of a novel that the scientist’s dying wife is writing. It is stuffed with plenty of bold and sweeping dialogue and even its lighting design is conceptual– the film begins in murky darkness and gradually unfolds into brightest light for the finale. But The Fountain manages to sidestep evaporating into muddled, self-conscious art and emerges as a resoundingly powerful and evocatively important piece of cinema that is a visual and emotive triumph.

Like all of Aronofsky’s films, The Fountain is about obsession. He explores this theme from many angle across his diverse but constantly impressive catalogue of features, but here he digs deep into the haunting remorse and regret of blinding grief as an incredibly pained Hugh Jackman breathes life to the lead role of Tomas / Tommy / or Tom (depending on the era), a character who claws at the door of eternal life, desperate to keep the one he loves from dying. It is this unrelenting denial of death that acts as the sole anchor for the film’s emotive core and the movie survives as an incredibly personal encapsulation of this pervading air of fear and denial by tying together gorgeously storyboarded shooting, startlingly imaginative effects, an ever-present, aching score, and career-best performances from Jackman and Rachel Weisz.

Particular mention must go to the visual effects for the space sequences where the awesome expanse of an enveloping dying star is represented not by cgi but micro-footage of chemical reactions in a petri dish. It’s without doubt the most dazzlingly mesmerising representation of the Universe ever seen on film and is completely captivating.

It’s not all praise, however. On repeat viewings, it’s easy to feel that thedark-to-light theme was overplayed, and even on Blu-ray the opening scenes are a little uncomfortable murky. There’s a smattering of unfortunate CGI here and there, some slightly unconvincing lab talk and at the end of the day this is certainly not a film for everyone. This is a very honest look into one person’s psyche, and as such there will be those of us who it resonates with and those who find it to be a pointless exercise.

It’s a fascinating and completely refreshing film that continues to be a unique, brave and incredibly affecting experience, with particular scenes lingering in the mind for prolonged periods. Its central theme of the acceptance or fear of death saddens me is timeless and resonant, and is cannily summarized in two of the film’s central pieces of dialogue:

‘Death is a disease, like any other; there is a cure and I will find it.’

‘Death is the road to awe.’

– Al White

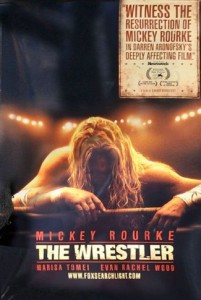

The Wrestler

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Robert D. Siegel

2008, USA

The core idea running through Darren Aronofsky’s filmography, is the fragility and impermanence of the human body. In Requiem for a Dream characters push their bodies to the limit through drugs, eventually losing possession over them, in The Fountain cancer ravages but spirits live on in multiple dimensions and finally in The Wrestler, a character makes a living cultivating and challenging his body on a daily basis; the cost however, is very steep.

Mickey Rourke stars in The Wrestler as Randy, a former Wrestling champ who continues to pursue his passion with gruelling weekend gigs. When it becomes apparent that his health is interfering with his come-back, Randy attempts to reconnect with the relationships he had left behind in the pursuit of his dreams. He strikes up a friendship with a stripper, Cassidy, who is also reaching the end of her career. He also finds his daughter, now a young adult, who wants nothing to do with him since his abandonment. He tries valiantly to make sincere human contact, but ultimately falls short.

A life-long pursuit of bodily “perfection” has left Randy emotionally crippled. The pursuit of the impermanent and the shallow has created a spiritual imbalance that he cannot overcome over the course of a few weeks. The physical obsession has focused Randy’s life on an aspect of existence that is shallow, self-centered and passing. This pursuit has gained him empty pleasure, but now that his body is fading these moments are less satisfying and will eventually run out.

Randy’s failures as a father at this late stage are not for lack of trying. He has mellowed and sincerely desires to rekindle a relationship with his daughter. Her reservations are valid and desperately, he attempts to make-up for all the time he lost and wasted. His anxiety is evident, even when he comes up short. His efforts are quite obviously a little too late, not only because their relationship is irreparably damaged, but his habits and attentions are too patterned and he is unable to break the cycle of self-involvement. The brief moments that they are able to share and forget their painful past are heartbreaking and serene, and one wonders why Randy does not try harder to salvage this relationship. It eventually becomes apparent though; it’s not so much an unwillingness as it is an inability to abandon his bodily pursuits.

His relationship with Cassidy is equally tumultuous, despite the fact that Cassidy is reasonable and understanding. Much like him, her body is her career, but she is well aware of the transient nature of a life built on something that once it reaches its peak, begins moving almost immediately towards decay. She is not mourning this loss, but celebrating the freedom that will come with it. Randy should have probably taken the same course, but chooses not to. This eventually alienates Cassidy and destroys their relationship as well.

Coming to terms with the film’s final scene, one wonders if Randy’s desire to pursue sincere human relationships is less a desire to reconnect as it is an attempt to further establish his immortality. There seems to be a point of realization in Randy, that he may be forgotten. His body has thrust him into the spotlight, but once that begins to fade he fears so might he. This interlude in his life is an attempt to forge a new identity, but he cannot meet the call. When given the opportunity to resurrect his career he takes it without hesitation, sacrificing his efforts to become a little more human. Is this acted out of fear or pure ego? Whatever the motive, it leads him further down a path of self-destructive.

The film’s gritty documentary look seems to brown the surroundings. Everything seems to be in a state of decomposition, the film itself embodies the effects of temporality on physical life. Art is life, but even that is not eternal, eventually fading due to exposure, environment and lapses in memory. As explored in The Fountain, only the power of memory is able to overcome our inevitable fate. All will be lost eventually; it’s a matter of holding on to what is important.

-Justine Smith

Black Swan

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Mark Heyman

Starring Natalie Portman, Mila Kunis, Vincent Cassell & Barbara Hershey

USA, 2010

In his new psychological musical Black Swan, director Darren Aronofsky has delivered a curious accompaniment to his critically embraced The Wrestler, with both films featuring blistering central performances of obsessive physical performers, individuals with punishing regimes whom operate in their own hermetic sub-cultures; worlds where the pursuit of perfection is placed before any due respect to health or salubrity, be it of a mental or physical dimension. With snippets of Cronenberg’s early body horror operas and shards of Polanski’s creeping sexual paranoia, Black Swan is one of the finest American films screened so far at the London Film Festival, a gracefully dizzying piece of work, from its opening overture to its dazzling crescendo.

Natalie Portman, who could be in line for a best actress nomination next year, is Nina, a high-strung and deeply ambitious young ballerina at the prestigious New York National Ballet. Nina is underenormous psychological pressure from her strident mother (Barbara Hershey) to excel where she could not, to become the lead dancer at a gala performance, an ambition denied to her due to her falling pregnant twenty years ago, she now investing all her thwarted dreams into her brittle young progeny. Initially overjoyed that she has secured the central role in a new season of Swan Lake, Nina becomes increasingly anxious and obsessed with her performance, a persistent neurosis that is compounded with the arrival of a promising young rival named Lily (Mila Kunis) who may have her own ambitions for the ingénue spectacle. Thomas Leroy, the troupes tyrannical creative director (played with a typical jovial intensity by Vincent Cassell) transfers his attention and affection to Nina from an aging dancer (Winona Ryder), a bitter and broken creature who may serve as a disturbing harbinger of Nina’s future trajectory. These numerous pressures and strains result in a slow mental deterioration as Nina incrementally comes apart at the seams, with strange hallucinations, curious injuries and medical ailments bewitching her growing ambitions, her role and her real life entangling in a mesmerizing study of obsession and subconscious torment.

Black Swan is an elegant, impeccably designed film in both form and content that should delicately pirouette into many cineastes’ films-of-the-year list. From the opening overture, Aronofsky takes his hand-held camera onto the stage, in amongst the actors, to provoke a tangible sense of immediacy and reality to the scenes. Shooting on grainy 16mm, the film has a documentarian style which seems counter-intuitive for such an ornate and reputedly glamorous milieu. As in The Wrestler, the smaller details, the specific rituals and equipment of the trade are explored to sketch in the minutia, through a deft burst of montages in the films earlier scenes the levels of devotion and dedication required of these young performers are laid bare.

The film is peppered with strong whites and blacks throughout its production design to emphasis the dual nature of Nina’s psyche, her distress almost spilling over to the real world, a duopoly that Aronofsky elucidates with a judicious use of mirrors and reflections. Nina’s deteriorating grasp on reality is masterfully charted, and the film is quite gruesome in places, with some disconcerting flourishes staged to ensure that the viewers, like Nina, are not sure of the validity of what may have just occurred. The film’s greatest triumph, however, is the integration of the original Swan Lake narrative into the film as this is very much a re-interpretation of that canonic narrative in a cinematic form, as Nina is also a creature whose love is thwarted due to a rival – at least in her perceptions – a rivalry and jealousy which seems certain to lead to a tragic result.

The cast of Black Swan is uniformly excellent, with Portman excelling as the driven yet fractured Nina, and sterling support from both Hershey as her concerned but coercive mother and Kunis as her corrosive feminine nemesis. Aronofsky incorporates Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake into a score by his regular collaborator Clint Mansell, a hybrid which provides a contemporary ambience to the menacing proceedings. Seductive, sensuous and sparsely sinister, Black Swan is one of the year’s best.

– John McEntee