It’s easy to make some wrong assumptions about Henry McGee, president of HBO Home Entertainment. Soft-spoken, low-key, well-tailored, he has none of the bombast or flamboyance of an entertainment industry “creative.” He does not reel off movie history trivia, nor go off on a loving endorsement of the latest overlooked art house treasure. But then neither does he revel in the opening weekend box office numbers of the latest blockbuster. Still, with his executive status, Harvard business background and reserved manner, it would be easy to dismiss him in knee-jerk fashion as what are disparagingly referred to as one of “The Suits” – the front office industry executives who writers, directors, actors, critics, and movie fans et al regularly target for their cinema lover’s scorn. To make that assumption would be to be as wrong as wrong can be.

There’s no doubt McGee is a shrewd businessman. He’s been with HBO since 1979, with HBO Home Entertainment (and its sundry precursors) since 1983, the video arm’s president since 1995, and has been instrumental in building the brand into one of the most successful non-studio-affiliated home video marketers, even expanding into overseas distribution in the mid-2000s; no mean feat in a highly competitive, constantly evolving arena.

But, at the same time McGee has been navigating HBO Home Entertainment through the shoals of the ever-shifting home market, he’s been president of the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater Foundation, sits on the board of the Sundance Institute, and the Film Society of Lincoln Center which produces the New York Film Festival. He’s also a member of the executive committee of the Black Filmmaker Foundation. The titles on video store shelves are not just “product” to him, but he does recognize the marketplace has a dynamic and demands that don’t always coincide with quality.

According to McGee, understanding the home entertainment business comes with a simple walk to the neighborhood video store. “If you want to know what rents, they’ll be the first things you see when you go in the store,” he says. “The biggest renting titles will be arranged on a ‘race track’ right when you come in.” As for those racks of older titles — the sections given over to “Classics,” “Romance,” “Action” and so forth — McGee draws a parallel: “It’s like a bookstore. Yes, you make money off your backlist, but the bestsellers are on a table you see the minute you walk in the door. Go into any Blockbuster and it’s the same thing. It’s the new, big titles that drive the business.”

And that business is critical to the studios. “The average theatrical release only makes maybe 20% of its money at the box office,” says McGee. “The rest comes from domestic home video, sales to pay- and free TV, basic cable, overseas sales. The big thrillers, the big action movies, they may pull in 50-60% of their total revenues from foreign.”

The dynamic of the home video market has evolved considerably over the last twenty-odd years, and listening to McGee talk about the early days of both video and cable is like listening to stories about the California Gold Rush: entrepreneurs jumping into an undeveloped business left and right, caught up in a maelstrom of quickly changing circumstances.

In the early days of home video, McGee reminds, the movie business was still primarily one of single-screen cinemas. “Home video made movies more accessible. The video store was – and still is — like the ultimate multiplex, except instead of ten, fifteen choices you (had) 12,000 titles.” The early 1980s saw the business take off with video distributors springing up like weeds to fill those shelves; companies like Thorn EMI, Vestron, and Media Home Entertainment among others.

Thorn EMI actually opened the door for pay-TV programmer Home Box Office’s entry into the home video business. In the early 1980s, HBO had been investing in theatrical movie production as a way of securing exclusive pay-TV rights to titles as well as having some say over what movies were being made. HBO’s theatrical investments included “pre-buys” (putting up money in advance of a production in return for pay-TV rights), partnering with CBS and Columbia Pictures to form major production company TriStar (later absorbed by Columbia after first CBS, then HBO pulled out), and being a partner in Silver Screen, a limited partnership providing financing for theatricals. Thorn EMI was one of the participants in Silver Screen. Not long after, Thorn EMI, feeling there was more growth potential with a partner than going it alone, approached HBO about the home video joint venture which became Thorn EMI/HBO Video.

HBO’s interest in getting into home video – which, at first, seemed contradictory to some, like setting one’s self up to be one’s own competitor – was based on some well-reasoned guesses about how home video was changing – and would change — movie entertainment. “We (HBO) used to be the first place you’d see current movies after their theater run,” says McGee. Uncut, uninterrupted movies delivered to the home had been the novelty driving HBO’s early years. “That was no longer the case with home video.” The company, says McGee, was also quick to note the growing revenue stream thrown off by the home video market, and saw an opportunity to profitably diversify the pay-TV company with a presence in the still-developing business.

HBO’s interest in getting into home video – which, at first, seemed contradictory to some, like setting one’s self up to be one’s own competitor – was based on some well-reasoned guesses about how home video was changing – and would change — movie entertainment. “We (HBO) used to be the first place you’d see current movies after their theater run,” says McGee. Uncut, uninterrupted movies delivered to the home had been the novelty driving HBO’s early years. “That was no longer the case with home video.” The company, says McGee, was also quick to note the growing revenue stream thrown off by the home video market, and saw an opportunity to profitably diversify the pay-TV company with a presence in the still-developing business.

Though the new venture had no direct affiliation with a major studio, the company soon became one of the largest of non-studio affiliated video distributors thanks to some key acquisitions. Orion Pictures, for example, had then been recently launched by the management team which had been successfully running United Artists for years but had left after the company had been taken over by TransAmerica. Thorn EMI/HBO’s acquisition of Orion home video rights gave the fledgling movie company a financial leg-up while simultaneously bringing major features like multi-Oscar-winning Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), No Way Out (1987), and Desperately Seeking Susan (1985) out under Thorn EM/HBO’s video brand along with older titles from the AIP library which Orion had acquired. Thorn EMI/HBO was also managing video rights for many TriStar titles, and a deal with Hemdale brought the company two of its biggest hits, Oliver Stone’s Oscar-winning Platoon (1986) and the rousing basketball tale Hoosiers (1986).

thanks to some key acquisitions. Orion Pictures, for example, had then been recently launched by the management team which had been successfully running United Artists for years but had left after the company had been taken over by TransAmerica. Thorn EMI/HBO’s acquisition of Orion home video rights gave the fledgling movie company a financial leg-up while simultaneously bringing major features like multi-Oscar-winning Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), No Way Out (1987), and Desperately Seeking Susan (1985) out under Thorn EM/HBO’s video brand along with older titles from the AIP library which Orion had acquired. Thorn EMI/HBO was also managing video rights for many TriStar titles, and a deal with Hemdale brought the company two of its biggest hits, Oliver Stone’s Oscar-winning Platoon (1986) and the rousing basketball tale Hoosiers (1986).

Eventually, Thorn EMI backed out of the movie business, selling its motion picture and home video interests to Cannon Pictures, and the video venture became HBO/Cannon Home Video. Cannon suffered its own business reverses and, in time, HBO bought out their interest. “At one point,” McGee jokes, “it seemed like we were trashing our stationary once a year to change the letterhead: Thorn EMI/HBO Video, to HBO/Cannon Home Video, to HBO Home Video!”

The period produced a boon for independent producers. “Prior to home video, if you couldn’t get a distribution deal with one of the majors, you didn’t get distributed at all,” says McGee. “Home video changed that. There were movies that only got made because of home video money.” Some of them might have been pure schlock, but they also included artistically risky endeavors like the demanding screen adaptation of cult favorite novelist Paul Auster’s The Music of Chance (1993), or the contemporary neo-noir, The Grifters (1990). Aftermarket commitments from home video as well as other ancillaries also supported big budget productions such as those from Carolco Entertainment which specialized in large-scale actioners like Rambo: First Blood, Part II (1985), Rambo 3 (1988), and Red Heat (1988).

The need of independent video distributors to constantly feed their pipelines, and of video stores to fill yards and yards of shelf space (there only being so many  major releases in a month) bred other strategies as well. For Vestron, the answer was to get into theatrical production. Despite a few impressive successes (i.e. Dirty Dancing,1987), the company couldn’t hit winning notes on any regular basis, and its theatrical failures not only pushed Vestron out of theatrical production, but finally brought the company down.

major releases in a month) bred other strategies as well. For Vestron, the answer was to get into theatrical production. Despite a few impressive successes (i.e. Dirty Dancing,1987), the company couldn’t hit winning notes on any regular basis, and its theatrical failures not only pushed Vestron out of theatrical production, but finally brought the company down.

The more widespread response was direct-to-video production. For the most part, says McGee, the direct-to-video movie was some kind of thriller: an action/adventure, a suspense story, a chiller. “The broadest audience moved toward the thrillers,” he says, “and they can be produced without a lot of effects. They also travel well,” he adds, into other ancillary markets like cable television and overseas distribution.

McGee recalls a direct-to-video production HBO Video acquired as typical example of the form. Soldier Boyz (1995) was budgeted near the top end of the $1-2 million range within which most of the more marketable DTV features fell, and starred home video regular leading man Michael Dudikoff and a supporting cast of little-known names in a The Dirty Dozen knock-off about an ex-Marine leading a strike force of youthful offenders to Vietnam to free a U.N. worker held hostage by revolutionaries.

The direct-to-video market remained strong into the mid-1990s when even the major studios began to capitalize on the form (and still do). Disney originally set the pace, regularly minting direct-to-video sequels and spin-offs to hits like Toy Story (1995)(Buzz Lightyear of Star Command: The Adventure Begins, 2000) and Inspector Gadget (1999)(Inspector Gadget 2, 2003). Universal also became a prolific producer of DTV follow-ups, for example turning out eight sequels to the animated The Land Before Time (1988), as well as The Hitcher II (2003), a belated DTV sequel to the bloody 1986 chiller. In 2006, Warners formed Warner Premiere for DTV purposes with its priority on developing DTV sequels to the studio’s theatrical box office hits i.e. The Dukes of Hazzard: The Beginning (2007).

The direct-to-video market remained strong into the mid-1990s when even the major studios began to capitalize on the form (and still do). Disney originally set the pace, regularly minting direct-to-video sequels and spin-offs to hits like Toy Story (1995)(Buzz Lightyear of Star Command: The Adventure Begins, 2000) and Inspector Gadget (1999)(Inspector Gadget 2, 2003). Universal also became a prolific producer of DTV follow-ups, for example turning out eight sequels to the animated The Land Before Time (1988), as well as The Hitcher II (2003), a belated DTV sequel to the bloody 1986 chiller. In 2006, Warners formed Warner Premiere for DTV purposes with its priority on developing DTV sequels to the studio’s theatrical box office hits i.e. The Dukes of Hazzard: The Beginning (2007).

Still another seismic change reconfigured the home video business. Many of the key independent production companies providing much of the theatrical product for the independent video distributors either failed (like Orion), or were acquired by the major studios (i.e. Miramax was taken up by Disney; Goldwyn by MGM). The 1990s consequently saw a general collapse of the independent home video distribution business. By 2004, only one sizable independent distributor remained: Artisan.

The era also saw an enormous consolidation at the retail level. In the early Gold Rush days of home video, cinephiles hoped – as they had with the advent of the modern cable age – the venue would finally provide ready accessibility to such cinematic gourmet fare as classic oldies, little-seen art house movies, cult favorites, overseas imports which had gotten little or no U.S. theatrical distribution, and so forth. But, the independently-owned video store providing such eclectic fare became a rarity, out-resourced, out-marketed, and generally out-flanked by national video store chains like Blockbuster and the now-defunct Hollywood Video which, at their peak, between them controlled half of the national video retail market, and who, despite their racks of backlist inventory, made their money primarily from recent, mainstream releases.

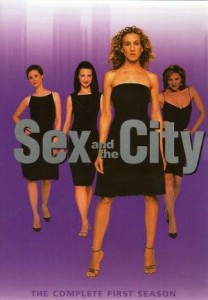

HBO Video responded to the new environment with a radical change in course which, luckily, coincided with a change in the programming model of parent HBO. Home video erosion of the pay-TV value of theatrical movies had pushed HBO toward increasing its investment in original programming, and, by century’s end, its developing expertise was paying off with popular and acclaimed series’ like The Sopranos, Sex & the City, Six Feet Under, and mini-series like From the Earth to the Moon and Band of Brothers. “We do very few movie acquisitions these days,” explains McGee. There are still a few theatricals in the mix — My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002), for example — but “Mostly we’re now offering HBO product.”

value of theatrical movies had pushed HBO toward increasing its investment in original programming, and, by century’s end, its developing expertise was paying off with popular and acclaimed series’ like The Sopranos, Sex & the City, Six Feet Under, and mini-series like From the Earth to the Moon and Band of Brothers. “We do very few movie acquisitions these days,” explains McGee. There are still a few theatricals in the mix — My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002), for example — but “Mostly we’re now offering HBO product.”

HBO Home Entertainment notwithstanding, McGee says the home video business remains primarily a movie-driven business, and, beyond that, a new-release-driven business with pretty definitive demographic demarcations. “There’s probably no one over thirty who’s rented Halloween (1978), and probably no one under thirty who’s rented On Golden Pond (1981).” Generally, however, the home entertainment audience, he explains, is broader than the theatrical audience which skews toward young males, with women more heavily influencing home entertainment choices than they do theater box office. Still, “There’s no question,” he says, “that the top-renting genres are the action movies, the thrillers, those kinds of pictures. Comedy comes next, and drama is a distant, distant third.”

Though box office now represents only a minor percentage of a movie’s total revenues, theatrical release, says McGee, is still the “primer” fueling the ancillary cycle. “The ultimate appeal in the ancillaries is driven by theatrical success.” Still, it is not uncommon for a movie which disappointed in theaters to do well in the home entertainment market. “Maybe they were released on a bad weekend; the multiplex always has a (quick) replacement lined up to take the place of a movie that opens weakly. Or maybe the stars are familiar to the DVD crowd and that helps move the title. In any case, it happens.”

Looking ahead, McGee sees two forces accelerating the pace of ancillary windows: “High productions costs and fears about piracy.” With the escalating budgets of the large-scale thrillers, studios are more concerned than ever before about the loss of revenue through piracy. “This,” says McGee, “has pushed the movies toward wider and wider releases.” Foreign no longer comes after domestic release, “but now you see simultaneous worldwide releases so that the studio can beat the pirates to the market.” It has also sparked debate in Hollywood about the distribution of “screeners,” copies of movies studios send to Motion Picture Academy members for Oscar consideration that the major studios maintain are fodder for pirate duplication.

At the same time, home availability has been moved up. “More often you see 50% week-to-week drops in box office, so the studios aren’t waiting as long to release movies on DVD.” Release for the home market can come as early as three months after a title’s theatrical debut, as opposed to six months which had stood as the industry standard for years.

At the same time, home availability has been moved up. “More often you see 50% week-to-week drops in box office, so the studios aren’t waiting as long to release movies on DVD.” Release for the home market can come as early as three months after a title’s theatrical debut, as opposed to six months which had stood as the industry standard for years.

Asked to speculate long-range about the business: “Some theorists – I emphasize some theorists – think there’ll be a time when a movie is released in all venues at once; you’ll just pay different prices to see it in different forms. You might, say, pay seven dollars to see it on home video, or five dollars for pay-per-view, or fifteen dollars to see it in a theater.” There have already been a number of experiments with simultaneous releases of some art house titles.

McGee is also curious what the long-term effect of Blu-Ray will be on home entertainment, remembering the impact DVDs have already had in just a few short years.

With DVD, the home entertainment market shifted almost overnight from a rental-driven to a purchase-driven dynamic, with consumers more likely to buy a title at a Wal-Mart or Target than a video store (hence Blockbuster’s ongoing financial troubles).

Another change: a lot of backlist titles which had filled out video store shelves in the VHS era didn’t make the transition. Says McGee, the studios looked at whatever wasn’t moving, or moving too slowly, and dropped those titles from active distribution. With the DVD, home video evolved into an entertainment option which actually offered less variety rather than more.

Like old books, the vintage Hollywood and classic titles and the cult favorites, says McGee, went “…out of print. Gone.”