The subject is revolution. The images are of people – young and old, cops and criminals, celebratory and despairing – confined in the frame by the structural elements of their surroundings. Interspersed among these images are visuals of genteelly rippling pools of water, reflecting the canopy of trees above. And bookending the short film itself are several shots of a lighthouse far out at sea, isolated among the sky and sea, the camera bobbing up and down with the waves. The last of those shots pushes in on the top of the tower, and for a brief moment, the lamp beams back at us.

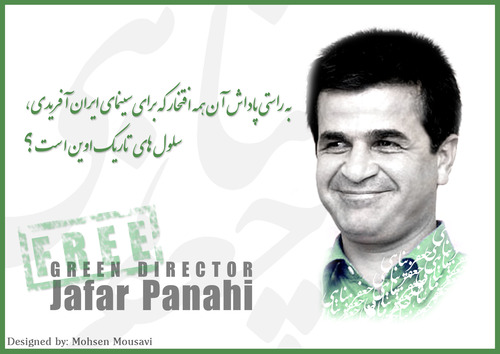

The film was produced by Cine Foundation International and made by an anonymous Iranian director (speculation on his identity is being discouraged to preserve his safety), primarily by stitching together pieces from The White Balloon, The Mirror, The Circle, Crimson Gold, and Offside – all films directed by Jafar Panahi. The film is dedicated to Panahi and Mohammad Rasoulof, both of whom are currently being held as political prisoners of the theocratic regime in their native Iran. On the opening night of the Berlin International Film Festival earlier this year, Isabella Rossellini read from the stage an open letter Panahi had written after being taken into custody: “They have condemned me to twenty years of silence. Yet in my dreams, I scream for a time when we can tolerate each other, respect each other’s opinions, and live for each other.” As the festival jury was introduced, Panahi was recognized with an empty chair at center stage, which, like the lighthouse, stood not just as a symbol but as a beacon.

Panahi’s films are not so much reactive commentaries on political conditions as they are direct provocations. Through cinema, he confronts the basic modes of societal organization in Iran, refusing to accept them as a natural ordering, and exposing them as an arbitrary relationship designed by the state to exercise power over the citizenry. For the audience, every frame is a call for relentless questioning, a challenge to imagine a fundamental restructuring of their world based on common human bonds. In life as on screen, Panahi embodies that drive to question. When Iranian authorities accused him of not obtaining the proper permission to film, he asked where the law requires such permission. When he was accused of giving foreign interviews, he asked by what law such interviews are banned. And when he was even accused of filming without a script, he asked what law prohibits improvising with non-professional actors. With every new dictate from the state, Panahi pushed the state to justify its actions to him and his countrymen.

But, unfortunately, authoritarian regimes always push back. Panahi was first arrested in July of 2009 while filming the funeral procession of Neda Agha-Soltan, a young woman killed by government paramilitaries during the crackdown on the protests contesting the legitimacy of Iran’s presidential elections that year, known as the Green Revolution. He was released shortly thereafter, but his passport was revoked, and in March of 2010 he was arrested again, this time at his home. While in his home, police seized film of the protests that Panahi had been preparing. After several months of imprisonment and de facto house arrest, the film finally led to charges of “assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic.” Panahi was convicted on December 20th, 2010, and sentenced to six years in prison, and barred from making films for twenty. The location and conditions of his detention are not known at this time.

The crimes Panahi was convicted of are lesser relatives of “Moharebeh,” or “war against God and the state,” a somewhat common and extremely serious charge in the Iranian judicial system, which can carry the death penalty. In February, Mir Houssain Mousavi and Mahdi Karroubi – two reformist presidential candadates and figureheads of the Green Revolution, who have been under house arrest since 2009 – were both formally accused of Moharebeh by the clerical Assembly of Experts. The charges were issued in response to Mousavi and Karroubi’s public call for a day of renewed protest on February 14th, serving as warning to those who planned to take part that they too risked joining the “corrupt on Earth.”

Hundreds upon hundreds did take to the streets though in Tehran, Shiraz, Isfajan, Kermanshah, Rasht, and elsewhere. Demonstrators marched through the capital peacefully until Basiji militants, dressed in plain clothes, began to agitate and disrupt the process from within. As the crowd became riled, police teams fired off tear gas canisters and rushed the mass of people, beating them with batons. In self defense, protesters threw rocks and set fire to garbage cans. Two universiy students were killed, and dozens more severely injured.

Mousavi, Karroubi, and other opposition leaders had called for the day of protest to capitalize on and show solidarity with the democracy movements consuming North Africa and the Middle East, from the Atlantic to the Persian Gulf. These were movements that no one had predicted, but sprang to life when a Tunisian fruit vendor responded to the seizure of his cart by lighting himself on fire in front of a Sidi Bouzid police station. Within days, marchers clogged the streets of Tunis, eventually forcing the resignation of strong-man President Zine El Abdine Ben Ali. Quickly on Tunisia’s heels, thousands of Egyptians occupied Tahrir Square in Cairo, and after over two weeks of tense hope and sporadic violence, pushed dictator Hosni Mubarak from power. Simultaniously, Yemeni activists organized “Days of Rage” in an effort to affect economic improvements and constitutional reforms. In Bahrain, the Shiite majority has peacefully petitioned the Saudi-backed Sunni monarchy for greater political freedoms only to be met with a brutal repression. In Syria, Ba’athist forces under President Bashar al-Assad have slaughtered citizens advocating independent political parties and open media. And in Lybia, a savage civil war between rebels and those loyal to Muammar Gaddafi has turned into a grisly stalemate, under the umbrella of a UN-authorized, American-enforced no-fly zone.

Reports of riots, sit-ins, and other acts of civil resistance have also come from Algeria and Jordan, Morocco and Iraq, Oman and beyond, each born of unique circumstances, but with an eye towards common goals.

Clearly panicked by the turmoil of their Arab neighbors, the Iranian mullahs have tried to frame these events as the successors to Iran’s own 1979 revolution – a revolution that began as a secular movement to oust the Shah – in that they are Islamist and hostile to West in nature. But there is little evidence of this in the streets. While extremist groups have participated in the popular uprisings, none of them have taken the lead, and in Egypt the Muslim Brotherhood has gone out of its way to show that its aims are subordinate to the people’s. Similarly, there is little proof to support the claim of many American Neo-Conservatives that the democracy movements show the success of the Iraq/Afghanistan wars and the Bush Doctrine. On the contrary, there is evidence to show that American abuses in the region have heightened criticism of human rights violations, making the the crimes of regional leaders harder to ignore.

The key word is humiliation. For decades now, Arabs and Persians have lived under regimes that have humiliated them by physically and spiritually degrading them and depriving them of their individual agency. These new democracy movements have not been primarily concerned with parliamentary minutia or the financing of political parties, but with realizing a society that recognizes and respects that which makes life worth living: the pursuit of the self. As one young Egyptian in Tahrir Square told NPR, “We will live with dignity, or we will die here!”

However, it would be fair to say that the Arab revolutions do owe a large debt to the Green Revolution, and not just for the way that young Iranians pioneered the use of social media sites like Facebook and Twitter as activism tools, but for the courage that so many nameless people showed. Unlike most of the Arab states, Iran has maintained a sizable urban middle class that, while disapproving of the regime, has been placated with amenities such as satellite TV and studying abroad. But the illusion of an open, equitable society was shattered when it became undeniable that voting had been rigged by the ruling clerics to keep hard-line President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in office. For the first few weeks of the Green Revolution, there was real hope that the size of the protests could, if not overthrow the regime, at least force a new election. But as the violence deepened, it became clear that the regime had the fortitude to outlast the movement. The Green Revolution did not die completely, but the average people, each with families and occupations, could not sustain it at full intensity.

Where the Green Revolution failed, movements in Tunisia and Egypt succeeded because at key moments their armies refused to murder large numbers of their countrymen. Those moments marked major shifts in the structure of their respective societies, realigning the relationship between the individual and the authoritarian state’s mechanisms of enforcement. But it is still far too early to say that Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions have totally fulfilled their promise. Protesters in Tunisia continue to demand the resignation of former Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi, the self-proclaimed successor to Ben Ali. And in Egypt the army remains in control of the state, promising an orderly transition towards free elections. Ultimately, the success of revolutions cannot be measured by the replacement of one system of government with another, but, to paraphrase historian Gordon Wood, by the transformations in relationships that bind people together. Revolutions are not won with guns, but with compassion.

****

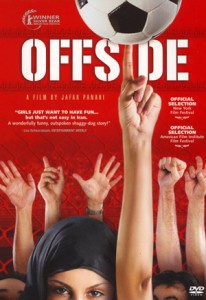

Of Panahi’s films, the one that captures that revolutionary spirit and truth most fully is 2006’s Offside, about six young women arrested at a World Cup-qualifying soccer match between Iran and Bahrain for breaking the ban on women attending men’s sporting events. Offside is a serious, scathing indictment of the subjugation of women in Iranian society, but it is also brimming with joy and excitement as the rhythms of the match course throughout the narrative. Although the on-field action is barely glimpsed, we are immersed in the sounds of the game. Accounts are relayed from sympathetic guards and amongst the girls themselves, uniting captives, captors, and the audience in breathless anticipation of the final whistle.

Of Panahi’s films, the one that captures that revolutionary spirit and truth most fully is 2006’s Offside, about six young women arrested at a World Cup-qualifying soccer match between Iran and Bahrain for breaking the ban on women attending men’s sporting events. Offside is a serious, scathing indictment of the subjugation of women in Iranian society, but it is also brimming with joy and excitement as the rhythms of the match course throughout the narrative. Although the on-field action is barely glimpsed, we are immersed in the sounds of the game. Accounts are relayed from sympathetic guards and amongst the girls themselves, uniting captives, captors, and the audience in breathless anticipation of the final whistle.

As the film opens, we find ourselves on a bus with, presumably, the youngest of the girls, who is trying to sneak into the stadium for the first time. The men around her see through her flimsy disguise, but are only bothered by her presence in so far as they are concerned that she will get caught. In fact, none of the men at the stadium are aggravated or upset that a girl is there. We even see some men helping other girls sneak in. And when the young woman we arrived with is chased down by guards, a crowd of men briefly tries to shield her from the guards before being shoved away.

The girl is led away to a holding area, where she joins the other five behind a flimsy metal barricade watched over by two provincial guards. Defying expectations, the guards are neither cruel nor aggressive, just as the young women are not subservient or delicate. The two groups banter back and forth, the girls trying to charm and tough-talk their way out of the pen. The guards grow annoyed, one snapping back, “Why don’t you get it? Men and women are not the same!” That may or may not be true, but the guard cannot explain how or why that should matter. “Why can’t women sit in the stadium,” quizzes one girl. The guard tells her that the men’s cursing is not fit for her ears. The girl asks why, then, can Japanese women sit in the Iranian stadium when their country’s team visits – “So, my problem is that I was born in Iran?”

The guard’s irritation grows, not so much with the girl, but with his inability to counter her questions with flimsy paternalistic logic. Later, in an aside to another police officer, he concedes that he would have let the girls go already if it weren’t for the threat of having his conscription extended if all the women reported arrested were not accounted for. No man can explain the ban, nor can they justify it except to say that they fear the consequences imposed by authorities. “Why did you come,” one guard asks almost desperately, “You are going to get us all in trouble!”

Offside makes masterful use of deep-focus compositions to place its characters amid the turbulent crowds and monolithic structures of the stadium. They are people situated within the institutions of their society, but their interactions are not bound by rules and regulations, but rather by what measure of consideration they are willing to extend to each other. Panahi’s camera takes in each character’s face with great generosity, and as the film progresses we learn to see those faces not as a man’s face or a woman’s, but the face of an individual.

In a sequence of long, fluid takes, one of the guards escorts one of the girls to the men’s restroom. He first makes sure that the stalls are clear, and then physically prevents other men from entering while she is inside. It is the film’s most virtuoso scene, and also its most revealing in that it shows how segregating public spaces by gender is not only a means of diminishing women, but of controlling men as well. Patriarchal forces marshall behavior through social divisions, and solicit obedience through the threat of force. By banning women from soccer stadiums, authorities make men complicit, and can justify all manner of encroachments. Or at least that is the idea – while the guard abuses the male fans, one boy makes room for the young woman to slide out the door.

The guard searches for her frantically, sulking back to his post. The girl is not gone for long though. She returns to the holding pen and her fellow female fans, not wanting to be responsible for delaying the guard’s discharge, and keeping him away from his family farm. “I felt sorry for his cows,” she says.

It is a revolutionary act in its selflessness and empathy, one that will be matched in the film’s final act. As the girls are taken away by bus to the vice squad, they convince the guards to let them listen to the last three minutes of stoppage time on the radio. We watch all the action play out on their faces in moments as exciting as any in cinema, and finally, as the bus is swallowed up by the celebratory crowds, the guards turn their backs and let the girls walk out doors. Moving through the throng, the young woman we began the film with lights seven sparklers – one for each of the Iranians killed at an earlier soccer match, including her friend – and waves them overhead. Closing on that image, Offside leaves us with a vision of national identity not based on subservience to theocratic commands, but on shared hopes and remembrances.

In the West we recognize the film cultures of authoritarian states like Iran as intrinsically political, because their cinema is shaped by its resistance to active political forces and censorship. Here at home – be that the United States, Canada, Western Europe, etc. – we have virtually no active censorship. Compliance with ratings systems is mostly voluntary, and restrictions on exhibition exist only in extreme cases. Our film culture is one shaped by passive economic forces, meaning, bluntly, what sells. Those economic forces tend to strongly steer film away from ideals, and towards lowest common denominators. For the most part, our film culture has been divorced from political discourse. We have two medias, one for ‘serious issues’ and one for ‘entertainment,’ each contemptuous of the other.

Jafar Panahi is just one of the many filmmakers and artists currently imprisoned – including Chinese sculptor and conceptualist Ai Weiwei, arrested earlier this month – who remind us that all art is inherently political, whether it acknowledges that fact or not. All art, particularly film, has the power to either sharply challenge our world view, or lazily confirm it. Reflecting upon that after every film we see is the best thing we can do to stand with those men and women who have been deprived of their freedom because of their art.

Keep the lighthouse in sight.