Directed by Carol Reed

United Kingdom, 1940

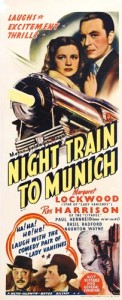

The title of Carol Reed’s 1940 wartime comedic thriller hardly tells the whole story. Perhaps hoping to capitalize off of the success of the two-years prior The Lady Vanishes, Night Train to Munich would have you believe that it’s an equally contained picture. That famous writers Frank Laudner and Sidney Gilliat wrote both is perhaps then, of no coincidence.

While there is an immensely successful third act that does take place primarily aboard a train, the film is far more sprawling and unfairly overlooked at the expense of its supposed successor.

successor.

Scientist Dr. Bomasch (James Harcourt) is forced to free Prague at the invasion of the Nazis. His daughter Anna (Margaret Lockwood) escapes from a concentration camp with the help of fellow internee Karl Marsen (Paul von Hernried) and meets her father in England, where father and daughter take up residence under the watchful eye of British intelligence man Gus Bennett (Rex Harrison). Revealing his true allegiance, Nazi-soldier Marsen kidnaps Dr. Bomasch and Anna, forcing Bennett to go undercover across enemy lines to bring them to safety.

One of the many things that makes Reed’s thriller so effective is how swiftly the action progresses. Each act could make up an entire film in and of itself: escape from a concentration camp, infiltration of Nazi headquarters, and finally, double-crosses aboard a moving train. That these smoothly segue between one-another is testament both to Laudner and Gilliat’s script and to Reed’s direction, which features a roving, mobile camera and slick blocking.

Hitchcock famously related his idea of successful suspense as a bomb under the table with no indication of when it will go off. Reed has many scenes that draw on this exact idea. One particular scene aboard the train car is pure master-of-suspense stuff. Two of Bennett’s school-buddies – the hilarious and inimitable Charters (Basil Radford) and Caldicott (Naunton Wayne) – discover that Marsen knows Bennett’s true identities. They concoct a scheme with which to warn their old friend: a note hidden under a donut on a tray being brought to his apartment.

In this example the note is the bomb, the donut is the table, and the various hands and eyes that may land on it first are its ticking clock. Reed’s camera at first places the offending donut in the foreground. His energetic cutting goes round from face-to-face, and the scene reaches a near climax when Marsen spins the platter, and unwittingly the note, closer towards him.

Rex Harrison’s Gus Bennett is more of a complex character than his surface nonchalance and arrogance warrant. In fact, as he is so frequently in disguise and undercover his real character is rarely glimpsed on-screen. Harrison really plays three different roles: the real Gus Bennett, his singing Englishman front, and his Nazi impersonator. Harrison delivers with ease, and the intentional cracks in his façade add to the humanity of a man forced to hide his true self at every turn.

The interplay between Bennett and Anna is peppered with cracks at one another’s expense and, unlike many of the concurrent Hollywood romances, the film does not culminate with an inevitable profession of love. Instead, as Bennett makes his difficult away across to Switzerland – Marsen at his back, Anna in front of him – there is true concern in her eyes. Perhaps it’s love, but her look only mirrors our own as the tension of the moment ratchets.

The interplay between Bennett and Anna is peppered with cracks at one another’s expense and, unlike many of the concurrent Hollywood romances, the film does not culminate with an inevitable profession of love. Instead, as Bennett makes his difficult away across to Switzerland – Marsen at his back, Anna in front of him – there is true concern in her eyes. Perhaps it’s love, but her look only mirrors our own as the tension of the moment ratchets.

– Neal Dhand