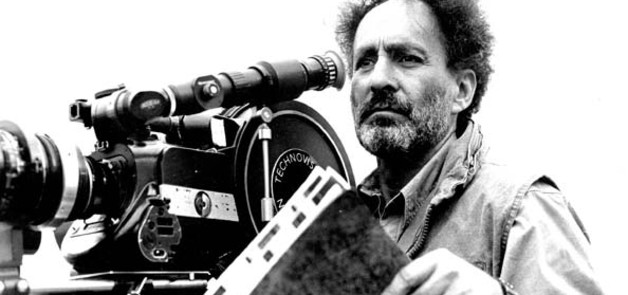

I interviewed director Monte Hellman about his recent film Road to Nowhere, future projects and his thoughts on daydreaming:

Neal Dhand: What is the current status of Road to Nowhere? Is it still making any theatrical rounds?

Monte Hellman: Opening in Japan around the first of the year. We’ve only really scratched the surface with countries. It’s played France of course, and Portugal, Israel, West Africa, Brazil, Italy.

ND: How has it been received?

MH: The French have always been friendly to my movies. The reception critically has been about 50/50 in France. It’s doing so much better than that in the US and I never expected that. I remember Two-Lane Blacktop was about 50/50. I think we’re somewhere around 80% on Rotten Tomatoes and not all of the critics are up there yet.

ND: There’s a definite synchronicity in your filmography. The Shooting, Ride in the Whirlwind, Two-Lane Blacktop– all are existential genre road movies in some way, shape or form. Do you see Road to Nowhere fitting into a similar categorization?

MH: To paraphrase Boris Karloff or Bela Lugosi (I can never remember which) in The Black Cat, “road perhaps, existential perhaps not.” Having studied existentialism as a child, I never know what it means when used to describe my movies. In my mind it refers to the distinction from the idealists, for whom essence precedes existence, and the existentialists, for whom existence precedes essence. That being said, yes I do believe there’s a formal and stylistic line between at least The Shooting, Two-Lane and Road to Nowhere. And a thematic line as well between Two-Lane and Road, the conflict between work and love.

ND: You intentionally blur the various lines of “reality” in Road to Nowhere, culminating in the sequence with Mitchell in the hotel room where another film crew is revealed. Is this your crew? Was it planned?

MH: It is my crew, as well as Mitchell’s crew, which we see in some other scenes as well. This reveal was actually filmed by Mitchell with his “prop” camera, and we only decided during the editing process to include it in the movie.

It was not in the script. It was something that he photographed in the scene where he picks up the camera. Literally, the script says that he picks up the camera and goes to the window to photograph the police, and so everything else that he does in that scene, including photographing the bodies, is something that he choreographed himself in that scene.

ND: Is there a specific reason you chose to use that in the edit?

MH: We just thought it had a power to it and people were very, very strongly affected both ways. Some people said, ‘you can’t do that,’ and other people said that it’s the best thing in the movie. So naturally we left it in.

ND: Is this a film to be solved? Can it be entirely solved?

MH: The things in the movie that many people have difficulty in unraveling aren’t meant to be confusing, i.e., when we’re seeing the making of the movie, and when we’re seeing the movie being made. It merely requires attention and observation, and for some seeing the movie a second time. But it’s pretty simple stuff.

But the more difficult riddles, i.e., whether everything we see after Mitchell plops the DVD in the laptop at the beginning is really ALL his movie, as well as how Nathalie can also be in the movie she’s watching, as well as what the bookends where Mitchell and Nathalie are watching the movie fit into this reality, may not be solvable. It’s like the riddle of life: “How did we all get here?” “God put us here.” “Who put God there?” Ad infinitum.

ND: The opening of the film – the long take of Shannyn Sossamon on the bed with the blow dryer – has been much talked about. The sound, the long take, her posture, all seem to indicate something foreboding, but still romantic. Do you see this as more than just an introduction of character? As a prologue somehow?

MH: I see it as much like Bobby Billings cleaning out his car before he goes to be shot. Why does someone put on nail polish before driving one’s car into a lake? (Or not.) It’s a way to make the audience ask questions, if not the major question. The final scene in this sequence is Laurel’s panic attack in the tunnel. That puts the final question mark to all these questions, and may indeed be the major question. It’s what hopefully keeps the audience glued to their seats until the end.

ND: I’m curious about your technique with the actors. Maybe a good place to start is a simple question, especially with the characters that are doubled as to whether they are playing the character, or the actor playing them. Did your actors always know whom they were playing?

MH: It shouldn’t be confusing. If she’s called Laurel she’s the actress, if she’s called Velma she’s Velma. I’m a bit surprised at the confusion.

ND: It’s less confusion than it is this merging or blending. Did you talk to them about bringing traits of say Laurel over to Velma and vice versa?

MH: I tell my actors no matter what, whether it’s another movie without people playing two roles or not, that what I want is them. I don’t want them to play a character; I want the character to become them. The same in this movie. If it’s Laurel Graham, it’s always Laurel Graham. If it’s Velma, it’s Laurel Graham playing Velma.

ND: Is there much improv in the film, or is it pretty close to the script?

MH: It’s very close to the script other than occasionally, if you do multiple takes, the actors will throw in a line or two to make it interesting and keep themselves fresh. Some of the funniest stuff was added that way. The line when Laurel is watching her dailies from the computer and in the scene and he says, ‘you should have been an actress, Velma,’ and she says, ‘or not.’ That was improvised in one take.

We did several takes of the rehearsal on the porch of the hotel. In one take he ad-libs, ‘who wrote this shit,’ and that was one of the takes we used as well.

ND: It’s hard to ignore that Mitchell Haven has the same initials as you. He also takes part in various films within Road to Nowhere: he’s the regular director on set, he shoots with his camera out the window at the police officers, he’s interviewed by Nathalie Post in the jail cell, and he’s the object of scrutiny by your own film crew. Is his position as director who loses control, who is alternately director and directed similar to how you see, or have seen yourself? How do you fit into the character of Mitchell Haven?

MH: The character of Mitchell Haven was indeed called Monte Hellman in an early draft of the script. The movie is part documentary of the way Steve Gaydos and I have made movies. But we changed the name of the character because he’s not Monte Hellman. He could be any number of young directors working today. In fact, as with all my actors, I tried to encourage Tygh to reveal the character of Tygh Runyan.

ND: In some way the mirroring that takes place in a film like The Shooting is very similar to the connection between Mitchell the director and Mitchell the prisoner. Is this a common theme you see – the same character as creator and destroyer?

MH: It’s not something I’ve ever thought about.

ND: What then about obsessive characters? Characters who have this end goal and whether or not it gets in the way of more important things – ie Velma/Laurel getting in the way of Mitchell making his movie – they’ll do it. Is this type of obsession a common theme?

MH: Well I don’t write these scripts. I think that just having a character with a goal is good drama. You want to have a character who wants something very badly, to give the audience something to root for

ND: Sure, there’s a goal there. It seems that more so than in traditional dramatic structure, that your characters will eschew all else to achieve that goal. Are these the scripts you’re drawn to?

MH: If you say so. It’s not something I think about when I read a script. I don’t really think when I read a script. I feel. And if something moves me then I want to make it.

ND: This is a film that has also heard comparisons with Mulholland Drive in its structure, view of Hollywood, and switching of characters. Was this an inspiration? I also see some Resnais in here.

MH: Resnais was definitely an inspiration. The only things I remember about Mulholland Drive are that Robert Forster seemed like he was going to be an important character, and then we never see him again, and that Naomi Watts seemed much more believable when she was acting (in her audition) than when she was being herself.

ND: Is it Resnais’ chronology? The way he deals with time, memory, or something else entirely?

MH:“I think that one of the things that appealed to me about Road to Nowhere is the fact that it dealt with time in really a novelistic way as opposed to a dramatic way. LIke in one of Steve’s favorites and mine, Stavisky. Of course there are elements of Last Year at Marienbad as well.”

ND: It seems to me that the major difference between Mulholland Drive and Road to Nowhere is that you are more interested in self-destruction and realization than in the nature of celebrity. These are characters that could be just as intriguing were they not famous. It’s the inter-connectedness and play with fantasy and reality that really counts. Is this your intent?

MH: I agree with your analysis, except for the relationship to Mulholland Drive, which I don’t remember. But this is after the fact, and only to the limited extent I can be objective about something so subjective. As for my intent, I don’t have any, other than to entertain and, hopefully, move an audience. In the inimitable words of Samuel Goldwyn, if I have a message, I’ll call Western Union.

ND: There’s been more than 20 years since your last feature film. Why Road to Nowhere? Were there any projects that fell through the cracks in between?

MH: Some fell through the cracks, like Freaky Deaky, but most were merely put on a back burner, like Love or Die, which I hope to do next, Cody and Farol and Dark Passion. Love or Die is a project I’ve had for almost 20 years. It’s a supernatural-romantic-spy-thriller, I think. I’m not very good at these kinds of descriptions. It’s a thriller and it’s supernatural and it’s romantic.

ND: Is that the next one? Are there others?

MH: I think it’s the next one. There’s another one that Steve Gaydos has written that could come first called Rattlesnake Shakedown. There’s another one he’s writing the script on that’s an adaptation of a novel called The Man Who Was Not With It. That’s based on a Herbert Gold novel.

ND: Is there a reason why you picked this script? There’s a lot to like in here in terms of doubling and riddles. Is that what stood out for you?

MH: I think I like things that are open to interpretation because it’s the way that I watch all movies. I remake every movie that I watch in the sense that I have my own daydream while watching it and literally I can’t tell you what the movie’s about, I tell you what my movie’s about – what I dreamed while watching it.

ND: Is that how you would like people to watch this movie?

MH: That’s how I hope people watch it, yes.

– Neal Dhand

[vsw id=”WkI4arhXbmM&feature” source=”youtube” width=”500″ height=”425″ autoplay=”no”]