“It’s funny how the colors of the real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen.”

A few years later, its enigma re-surfaced. One of my friends—a strictly raised, church-going boy—told me all about this crazy film he had watched. He said it was unlike anything he had ever seen, but that I shouldn’t tell anyone because he didn’t want his parents to find out. Prone to exaggeration, I expected him to name something like Scream or The Frighteners – but no, it was the one film I had always wanted to watch. And, “O my brothers,” one thing I could never stand is to have a friend know more about film than me, for I was competitive and had yet to learn that “initiative comes to thems that wait.” But, you see, I was blocked once again. Now living in a small town, the local video store didn’t have any copies of A Clockwork Orange; and “feeling a bit shagged and fagged and fashed,” I tried my best to forget about it.

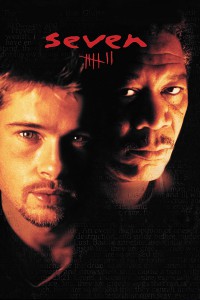

Not long after, I ended up seeing a different film that would forever mark my filmic  sensibility. I’d say it was around 1998 on a typical Saturday night when my family rented Se7en. I still remember the collective gasp we uttered at the end, and the gloominess I felt for the rest of the weekend. It was the first time a film really got under my skin. I had seen plenty of gritty crime films and was a die-hard X-Files fan, but something about Se7en shook me to the core. I was mesmerized by the dreary aesthetic and completely drawn to the intellectual nature of the violence. It was here where I started to realize how complicated human motivation is; how capable of cruelty we all are. And on a cinematic level, I also realized how important it is to know about directors.

sensibility. I’d say it was around 1998 on a typical Saturday night when my family rented Se7en. I still remember the collective gasp we uttered at the end, and the gloominess I felt for the rest of the weekend. It was the first time a film really got under my skin. I had seen plenty of gritty crime films and was a die-hard X-Files fan, but something about Se7en shook me to the core. I was mesmerized by the dreary aesthetic and completely drawn to the intellectual nature of the violence. It was here where I started to realize how complicated human motivation is; how capable of cruelty we all are. And on a cinematic level, I also realized how important it is to know about directors.

After pledging allegiance to David Fincher, I moved on to Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, and Francis Ford Coppola. They introduced me to the possibilities of cinema, but it was when I was 18 and finally got a chance to see A Clockwork Orange that my mind was blown open. Having recently received a PS2 for my birthday, I decided it was time to start collecting DVDs. Upon discovering Warner Brothers had released A Clockwork Orange a year or so earlier, I headed to the mall and upon showing two pieces of I.D. to a non-believing cashier (I looked 15 until I was like 22) I could finally “viddy” Kubrick’s film for the first time (I wish I could say that A Clockwork Orange was my first purchase, but sadly it was my second – Mallrats at a whopping $37.99 was the first. Sigh.)

Having waited most of my teenage years to see Alex (Malcolm McDowell) and his droogies in action, when the moment eventually came, it was an altogether different experience than I had anticipated. Maybe it had to do with my expectations, but going in, I looked forward to being shocked and amazed by the brutality. However, the conflicting nature of Alex caught me completely off-guard. I had expected the “ultraviolence” to be over-the-top and gory. Instead, it was both stylized and realistic; a combination I found extremely unnerving. For the first time, a film was actually causing me unease. With Se7en, I learned that a film’s aesthetic could have a strong influence on the viewer. But with Se7en, I was comfortable with what I was watching. Though the subject matter is heavy, I knew when to gasp, when to be surprised, and how to process what I was seeing. With Clockwork, I learned that films didn’t have to be like that. A film could be philosophical, challenging, and oddly compelling, without ever keeping you in a comfort zone. In other words, “it was gorgeousness and gorgeousity made flesh. It was like a bird of rarest-spun heaven metal or like silvery wine flowing in a spaceship.”

Looking back, it’s not the act of viewing that I remember clearly, it’s the way the film stayed with me. I remember sitting in the shower, my dad yelling at me for taking so long, my thoughts focused on the title. Why an orange, I wondered. And then I began to think about how the film looked. How the milk bar was one of the most interesting places I had ever seen. And I also had that light bulb moment, that spark, where I realized my interest in film was about to move from hobby to obsession. A Clockwork Orange gave me the kind of thrill that no person, no book, no drug, and no physical act had ever provided. I was completely enthralled, and “suddenly I viddied what I had to do.” I had to devote my time to watching and reading about movies.

Looking back, it’s not the act of viewing that I remember clearly, it’s the way the film stayed with me. I remember sitting in the shower, my dad yelling at me for taking so long, my thoughts focused on the title. Why an orange, I wondered. And then I began to think about how the film looked. How the milk bar was one of the most interesting places I had ever seen. And I also had that light bulb moment, that spark, where I realized my interest in film was about to move from hobby to obsession. A Clockwork Orange gave me the kind of thrill that no person, no book, no drug, and no physical act had ever provided. I was completely enthralled, and “suddenly I viddied what I had to do.” I had to devote my time to watching and reading about movies.

From that point forward, I started power-watching films. Every week, I would rent eight films for $10 – all old releases and all on VHS. It was the first year after high school, and at this point, I was only working part-time. During the start of grade 12, I had thought I wanted to do a degree in computer science, but after a semester of hating advanced math, I figured university was out of the question. I didn’t have trouble with high school per se, but I also never saw the point. I spent most days daydreaming and quickly became convinced that I had no discipline. It was only after my first year of getting serious about film that I decided I could apply myself, and the following year I began a Bachelor of Arts program.

I cherished my year of freedom, though. During that time, I discovered Hitchcock, the Coen brothers, Polanski, Lynch, and of course, more Kubrick: Full Metal Jacket was the film I would show my friends, The Shining was the one I would want to debate, and 2001: A Space Odyssey was the film I would measure taste with: ‘What? You don’t like 2001? You’re no film lover.’ A Clockwork Orange was still my favorite, though, and I would watch certain scenes over and over, trying to master the rhythm of Alex’s unique slang. And I even started pumping the “ol’ Ludwig van” whenever I had the chance. Oh yes, “my brothers,” it was the “dreaded Ninth” and “eggiwegs” and “steakiwegs” for me.

In her now infamous review of the film, Pauline Kael states that “the numerous rapes and beatings have no ferocity and no sensuality; they’re frigidly, pedantically calculated, and because there is no motivating emotion, the viewer may experience them as an indignity and wish to leave.” She’s right, but this is the reason why so many people are drawn to the film. It offers an affecting experience not through sentimentality or catharsis, but through ambivalence. In regard to an ideological critique, A Clockwork Orange is prone to criticism, as Alex is by far the only likable character in the film. And while Kael and other detractors view this heavy-handedness as a drawback, I see it as provoking. It doesn’t matter if you agree or disagree with the film’s nihilist views; what matters are the feelings the film conjures up. Like all of Kubrick’s work, the primary function is to overtake the spectator, and A Clockwork Orange is his most aggressive work. When you watch the film for the first time, you really aren’t sure what you’ve witnessed. Yes, the spectator is forced to identify with Alex. And yes, the film is cold – but that’s the point. It doesn’t have the most insightful politics, nor is it a film that everyone should watch, but if you’re looking to be challenged by ambiguity, whether negatively or positively, you can’t go wrong with A Clockwork Orange.

Kubrick made a career out of making films that audiences were not used to seeing, and to this day, I still return to A Clockwork Orange whenever I want to be immersed. While it is no longer my favorite film (that honor is shared by Stalker and Rosemary’s Baby), or even one of my favorite Kubrick films (2001 and Eyes Wide Shut are a cut above the rest), Clockwork will always be my first love, the impetus for my cinephilia. With the hindsight of now having watched thousands of films since first seeing Alex and his droogs, I have yet to find a mise-en-scene that rivals Clockwork’s in terms of pure exaggerated brilliance. It’s been over 40 years and the interiors still seem futuristic, and that “my brothers” is insane.

Kubrick made a career out of making films that audiences were not used to seeing, and to this day, I still return to A Clockwork Orange whenever I want to be immersed. While it is no longer my favorite film (that honor is shared by Stalker and Rosemary’s Baby), or even one of my favorite Kubrick films (2001 and Eyes Wide Shut are a cut above the rest), Clockwork will always be my first love, the impetus for my cinephilia. With the hindsight of now having watched thousands of films since first seeing Alex and his droogs, I have yet to find a mise-en-scene that rivals Clockwork’s in terms of pure exaggerated brilliance. It’s been over 40 years and the interiors still seem futuristic, and that “my brothers” is insane.

I often wonder which contemporary films—aside from superhero nonsense—are leaving a stamp on young, impressionable minds these days. After watching Kim Ki-duk’s Moebius last year, I wondered what an inexperienced viewer would think. Would it influence them to seek out challenging movies, or would they turn away for good? All I know is that adult-minded cinema no longer carries the same kind of cultural power it once had. With millions of videos available online, controversial films are not as appealing as they used to be.

I think we’re going to see a lot of people grow up with television being their biggest influence. Dark and dreary shows like Top of the Lake and True Detective are getting more praise than the average adult-minded film—and rightly so. Still, I think there are a large amount of mainstream viewers out there waiting for a modern Clockwork to overtake them. We just need a director with the skill-set to pull it off. I’m thinking, maybe a combination of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Ben Wheatley, and the aforementioned Kim Ki-duk might do the trick. But who am I kidding – there was, and only ever will be, one Stanley Kubrick.

Ask any film lover and I bet at least one Kubrick film influenced their taste. He may not have been the most prolific director, or the easiest to connect with, but he made affecting, thought-provoking cinema. Not the kind that gives you a “nice, warm vibrate-y feeling all through your guttiwuts,” but the kind you never forget.

— Griffin Bell