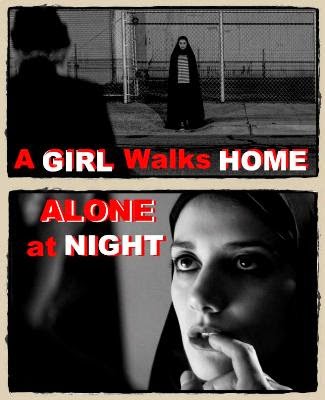

The phrase “first Iranian vampire western” will follow A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, and its director Anna Lily Amirpour, until the end of cinema itself. A year and a half after it glided sexily into Sundance, the movie has made waves for its genre play, for Sheila Vand’s already iconic vampire look, and for its incredible, eclectic soundtrack. The movie has been in vogue ever since, even though there appears to be little beneath its chador-clad exterior to chew upon. Part of the explanation is never mentioned in its buzzy tagline, but most of the attraction is really down to its story of misfit rebellion, a James Dean tale with a Donnie Darko-esque soundtrack, by way of Iran.

There are, as is frequently mentioned, a lot of similarities with Jim Jarmusch’s earlier movies Stranger Than Paradise or Down By Law. This extends beyond the black-and-white shots of urban tedium, but also in some of its musical choices, most notably opener “Charkhesh E Pooch” by Iranian ex-pats Kiosk. Accompanying a shot of leading guy Arash (Arash Marandi), wearing shades and a white t-shirt tucked into his black jeans, while smoking a cigarette and leaning on some dilapidated old fence in suburban California – the most ‘Jarmusch’ image in recent memory – the track sounds just like the Euro-tinged accordion fare from Tom Waits’ post-Swordfishtrombones discography. At this point, it seems as though John Lurie is about to stroll onscreen, bored out of his mind. Singer Arash Sobhani even resembles Waits’ guttural croon in its formative stages of whiskey-rinsed corrosion.

Visually, the movie is established as being mainly about style, as Arash spends the rest of the opening credits walking home with a cat he has just found. The music, however, deepens that understanding by locating precisely where that style is borrowed from, and what Amirpour – writer, director, soundtrack assembler – plans to do with that influence. Very little is actually happening; it’s essentially just a guy and a song. But it clearly asserts why the soundtrack of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is the real masterstroke, even above the striking black-and-white cinematography, and the chameleonic performance by the stunning Vand.

the opening credits walking home with a cat he has just found. The music, however, deepens that understanding by locating precisely where that style is borrowed from, and what Amirpour – writer, director, soundtrack assembler – plans to do with that influence. Very little is actually happening; it’s essentially just a guy and a song. But it clearly asserts why the soundtrack of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is the real masterstroke, even above the striking black-and-white cinematography, and the chameleonic performance by the stunning Vand.

This, of course, is true to a lot of movies, and anybody who has ever paid attention to the music in a film will tell you that it’s just as important as the image. However, Amirpour’s movie could have easily fallen prey to accusations of self-indulgence had the wrong soundtrack been provided (even though it occasionally does anyway). But what could have been pretentious stylisation is dressed as youthful energy because of the music picked by Amirpour, and for that reason, it deserves way more attention than the single sentence usually dedicated to it in reviews.

Though it doesn’t transfer well to English-speaking audiences, the bands that most commonly appear on the soundtrack – Kiosk, Radio Tehran – write songs that are critical of the Iranian state, and were forced into exile through censorship of expression in their native land. While those versed in the Persian language will truly grasp their rebellious spirit, the bands’ music is nevertheless undercut by a cynical drive that transcends the language barrier. Radio Tehran’s “Gelaye” is, again, reminiscent of something from the soundtrack to Donnie Darko – half “The Killing Moon”, half “Under the Milky Way” – and it’s here that the movie begins to adorn a gothic adolescent feel. This enhances the lonely, longing stares of its protagonists, as well as the overall themes of urban isolation and, intrinsically, the vampire as a Lost Boys appropriation of teenage fervour.

Amirpour has surprises up her sleeves, however, once she has so effortlessly established the mood. While some of the soundtrack leans into David Lynch territory (the scene in which the Girl encounters the young boy aurally recalls the Winky’s scene in Mulholland Drive), it is at once jarring and wholly natural that some of the music sounds so similar to Ennio Morricone. Heavily featured Portland, Oregon band Federale create music in a spaghetti western style, complete with harpsichords, thundering guitars, and wordless sopranos, although with a darker edge bearing a touch of neo-classical bands such as Dead Can Dance.

Their music is what helps to craft A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night as a western while continuing to retain its gothic tone, and it is first introduced following the death of Saeed (Dominic Rains), when Arash begins to sell ecstasy to make a living. Their track “Sarcophagus” (which initially resembles the music from Jarmusch’s retro-goth Only Lovers Left Alive) plays over a slow montage sequence in which the Girl washes off Saeed’s blood from her attack, Arash uses his earnings to pay for his medical bills, and his father Hossein (Marshall Manesh) suffers from heroin withdrawal. Meanwhile, there are shots of the landscape’s oil derricks churning while Saeed’s body is thrown into a ditch along with countless other corpses. What the Leone-esque soundtrack of “Sarcophagus” does is anchor the meaning of this sequence, suggesting that in the fictional, semi-deserted Bad City where the movie takes place, these are the laws of the land, and the mixture of drugs and violence are the only means by which one may survive beyond sunrise.

After Federale’s music helps to introduce western elements to the movie, it also sheds extra light on Sheila Vand’s vampire; she becomes a law-maker, a knight errant abiding by and fulfilling her own moral code, much like the heroes of the old west. She puts the fear of God into young children, protects her love interest Arash, and murders the abusers of damsels in Bad City, keeping track through the watchful eyes of her spirit animal, the chubby cat that roams unnoticed.

But while the first half is all sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, with the Free Electric Band’s pounding techno and Bei Ru’s Eurasian trip-hop, British neo-wave band White Lies provide a pivotal moment in a musical number similar to the Sonic Youth scene in Hal Hartley’s Simple Men. Their Cure-via-Interpol track “Death” is not only beautiful in its aching eighties retro – fitting with the gothic tones of Radio Tehran – the lyrics equate love with the metaphor of travelling in an aeroplane: the thrill of lifting off coupled with the fear of falling. It’s entirely appropriate to accompany the moment a rare connection is felt by these two wandering introverts, with Arash and the Girl gradually embracing in her bedroom, the dramatic irony of danger lingering overhead.

As such, the Girl knows this could end in disaster due to her bloodsucking tendencies, so while she lifts up Arash’s head, baring his neck, Harry McVeigh sings over and over in a quieter moment, “yes, this fear’s got a hold on me”. But as the guitars roar back in, and McVeigh’s modest croon breaks into a desperate cry, the Girl instead concedes to her overwhelming attraction, and decides to rest her head upon Arash’s chest. Set against the pop culture images that fill the lonely Girl’s wall, and contextualised by the alienation otherwise experienced by the characters in question, the power of this moment could never be overstated.

Although this song is ostensibly nothing like anything else in the movie, it is entirely in keeping with the overall spirit. Aside from the deliberately off-kilter techno, which plays in Saeed’s home as he snorts cocaine and pumps iron to impress the Girl (who is really only there because she wants to kill him), very little of the soundtrack deviates from the set tone, which is likely due to Amirpour’s tendency to choose her music before the script is even finished. But while it is all part of a larger pattern, each individual track still holds its own meaning, and affects the action in profound ways. As a movie, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night fares better with those invested in the cinema of cool, but even for audiences who decry the style-over-substance aesthetic, there is no denying that the style itself is well-considered and perfectly executed, and in conjunction with its soundtrack, establishes a substance entirely within itself.