“Brandy Burre is Actress.” So begins Robert Greene’s new documentary about the daily life of Brandy Burre, an ostensibly retired television actress who has not taken a role in years and has since settled down in upstate New York to raise her two kids. Notice the odd construction of that sentence: Brandy is actress, Greene tells us. He seems to be fascinated by the idea that Brandy never stopped acting, but that instead, in motherhood, she simply took her latest, most challenging role, one which she must perform daily and to which she has to give herself over completely. Brandy cooks and cleans. She takes her kids to school and goes grocery shopping. In short, she does everything a mother is expected to do, and she does it admirably, but this takes its toll. To Greene’s camera (and, really, to anyone who will listen, like the woman who does her hair), Brandy desperately confesses her desire to break free from these expectations, to let her absent husband take care of their kids while she resumes her career and the life she left behind.

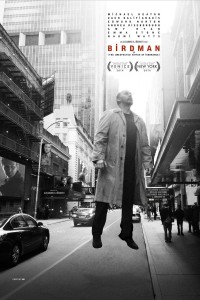

Alejandro González Iñárritu’s fictional Birdman follows film star Riggan Thomson — famous for his superhero Birdman — played by Michael Keaton — best known to audiences as Batman — as he tries to regain his former glory by directing and starring in a play adapted from Raymond Carver story. With the recent wave of superhero films flooding the market (a real world occurrence that the movie incorporates into its world) Riggan is pressured to put his costume back on, to return to the character that made him. He disagrees. He’s tormented by the avian figure, who hovers, like a devil, over his shoulder, constantly berating him, beating him into submission. Riggan meditates, medicates and levitates. He tries everything imaginable to escape Birdman, including a suicide attempt. No matter how much he acts out, like Brandy, he’s stuck in a nightmare partly of his own making.

Insecure about their status as serious actors and undergoing midlife crises of sorts, both Brandy and Riggan yearn for validation. They fear that they have disappeared into the roles they accepted earlier in life and believe that the only way to bring meaning back into their lives is to create something new. As they move forward, the films continue to mirror one another by charting the development of this period of crisis in the main characters’ lives until their resolutions, which are brought about partly through the making of the actors’ latest projects. Keaton’s character, in his attempt to put on a play, unwittingly gives his best performance off-stage as he prepares his impossible adaptation. Ultimately, he regains fame and acclaim not so much for his stage work, but mainly for his performance surrounding it, such as his impromptu trip through Broadway in his underwear, a bizarre incident that makes him a trending topic on twitter (which, as his daughter assures him, is a new form of power) and a subject of conversation for the first time since the third Birdman. Brandy, on the other hand, does not get any major roles, at least not as of the ending of the film, but she uses Greene’s documentary, including its revelation of her extramarital affair, as a platform to finally break free from her motherly role and to get back to the world of acting. Through Actress, she delivers what could easily end up being the best performance of her career as “herself.”

Insecure about their status as serious actors and undergoing midlife crises of sorts, both Brandy and Riggan yearn for validation. They fear that they have disappeared into the roles they accepted earlier in life and believe that the only way to bring meaning back into their lives is to create something new. As they move forward, the films continue to mirror one another by charting the development of this period of crisis in the main characters’ lives until their resolutions, which are brought about partly through the making of the actors’ latest projects. Keaton’s character, in his attempt to put on a play, unwittingly gives his best performance off-stage as he prepares his impossible adaptation. Ultimately, he regains fame and acclaim not so much for his stage work, but mainly for his performance surrounding it, such as his impromptu trip through Broadway in his underwear, a bizarre incident that makes him a trending topic on twitter (which, as his daughter assures him, is a new form of power) and a subject of conversation for the first time since the third Birdman. Brandy, on the other hand, does not get any major roles, at least not as of the ending of the film, but she uses Greene’s documentary, including its revelation of her extramarital affair, as a platform to finally break free from her motherly role and to get back to the world of acting. Through Actress, she delivers what could easily end up being the best performance of her career as “herself.”

In effect, both films stake their success or failure on these central performances. Luckily, Michael Keaton and Brandy Burre pull through with some amazing work. Keaton’s paranoid, perpetually crazy-eyed thespian enhances the electric feel of the movie achieved by Inarritu’s decision to make the movie seem as one continuous take. And although Birdman appears to be the more overtly theatrical and exaggerated of the two, in Actress, Greene occasionally grants Brandy control of the film at which point she goes on extended rants dealing with personal and professional issues like the lack of roles for women over a certain age (a depressing fact she illustrates with personal anecdotes from her experience on The Wire). Brandy’s thoughts are so articulate and powerfully delivered that they almost seem scripted, too good for someone to just improvise on the spot like she does. Whatever the case, it’s impressive.

Thematically, too, the films resemble one another. Both films are obsessed with the idea of authenticity, something they express through their style. They achieve a magical or poetic realism that seamlessly blends reality and artificiality. Are the images onscreen true? Are they made up? Can Riggan really levitate? Is Brandy’s movie-like affair real or staged? If the films are trying to make a larger point with their embellishments, does it even matter? Art and life (particularly when dealing with an actor’s life), Iñárritu and Greene argue, are intricately connected to the point where they can hardly be separated.

Birdman, although fictional, attempts to be lifelike as possible. Iñárritu shot it to look like one fluid take, a visual strategy that mimics the immediate quality of the theater, a technique guided towards creating the illusion of reality by making the spectator feel present at all moments. Meanwhile, Actress, a documentary, creates a distancing effect by emphasizing the artificialities of everyday life. It is simultaneously calculated and melodramatic, and it tries to elevate mundane reality toward the cinematic. Greene’s images are carefully composed and edited to give meaning to Brandy’s everyday experiences. The first shot of the film, for example, shows Brandy at the center of a perfectly framed shot with a bright red dress, her back to the camera, washing dishes. It’s not the sort of shot one normally sees in documentary film, which tends to be visually indifferent. Instead, it provokes the viewer to think about the image and the actions Brandy is performing, actions she feels inadequate carrying out. We hear Brandy speaking in voiceover, another cinematic technique Greene uses to let the viewers know they are watching a film. “I tend to break things,” she says, a loaded phrase complicated by the fact that it’s a line from one of Brandy’s previous roles, and not a sincere, spontaneous thought. Does she mean it or is this merely a premeditated show for the camera?

In Actress and Birdman, while reality and fiction blur, true cinema emerges.

– Antonio Guzman