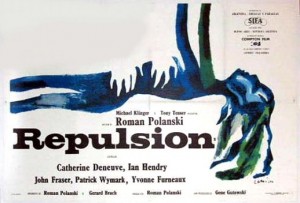

Repulsion (1965)

Repulsion (1965)

Dir. Roman Polanski

United Kingdom – 105 minutes, B&W

Criterion Spine # 483

Warning: Here be spoilers.

Like flies to the gooping carcass of a skinned rabbit, Repulsion invites a lot of intellectual psychobabbling that usually amounts to the same things being said by different people. We can all pretty much agree what this film, a creepy, precise exercise in claustrophobic terror, means. That is to say that it’s a story about a troubled young woman who, trapped alone in an apartment for a couple of weeks, becomes homicidal as she battles more sexual anxiety than you can shake a stick at.

Now, if you want to hear about what a great actor’s director Polanski is and how textbook-precise the use of sound, music, surrealistic imagery and the female orgasm adds to the crumbling of one woman’s mind, allow me to point you to the succinct and intelligent essays that are part of the Criterion package, as well as the two making-of docs on the disc (especially Claude Chaboud’s great Grand Ecran segment, which uses some pretty choice behind-the-scenes footage and interviews with a young Polanski).

What I want to focus on, instead, is what this movie can potentially be about, how a fractional shift in perspective makes this a very different film altogether. My basis for this hypothesizing is based mostly on my view of Polanski as a very deliberate filmmaker. I imagine this is one of the main reasons he’s often compared to Hitchcock, in that there is selfom a detail that goes to waste. I was having a conversation with a friend last night and I was telling him how, despite the surrealistic imagery and overall trippiness of the film, it’s actually quite straightforward, certainly the most straightforward of the so-called ‘Apartment Trilogy’ that includes Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Tenant (1976). If you were to trace the arc of Catherine Deneuve’s character, Carol, then it would look something like this: she starts crazy. She gets crazier. Her sister leaves and, without constant supervision, she goes completely off-the-wall (almost literally) and kills a couple of creeps.

What I want to focus on, instead, is what this movie can potentially be about, how a fractional shift in perspective makes this a very different film altogether. My basis for this hypothesizing is based mostly on my view of Polanski as a very deliberate filmmaker. I imagine this is one of the main reasons he’s often compared to Hitchcock, in that there is selfom a detail that goes to waste. I was having a conversation with a friend last night and I was telling him how, despite the surrealistic imagery and overall trippiness of the film, it’s actually quite straightforward, certainly the most straightforward of the so-called ‘Apartment Trilogy’ that includes Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Tenant (1976). If you were to trace the arc of Catherine Deneuve’s character, Carol, then it would look something like this: she starts crazy. She gets crazier. Her sister leaves and, without constant supervision, she goes completely off-the-wall (almost literally) and kills a couple of creeps.

That’s all well and good but, frankly, it isn’t that interesting (to me, anyway). The way I see it, that kind of interpretation leaves the end to be sort of this passive inevitable, where it was simply a matter of time before Carol becomes a victim of her own addled mind. But what if Carol is actually an active character? What if, instead of viewing her as this subject we’re supposed to observe, she’s this person with whom we are meant to empathize? What if she isn’t crazy and the dangers she sees in men and sex are legitimate dangers? In that conversation with my friend, I told him: “Repulsion isn’t actually a psychological thriller. It’s a zombie movie.”

That’s all well and good but, frankly, it isn’t that interesting (to me, anyway). The way I see it, that kind of interpretation leaves the end to be sort of this passive inevitable, where it was simply a matter of time before Carol becomes a victim of her own addled mind. But what if Carol is actually an active character? What if, instead of viewing her as this subject we’re supposed to observe, she’s this person with whom we are meant to empathize? What if she isn’t crazy and the dangers she sees in men and sex are legitimate dangers? In that conversation with my friend, I told him: “Repulsion isn’t actually a psychological thriller. It’s a zombie movie.”

His response was something along the lines of: “Bullshit.”

Now, yes, it is a stretch to call Repulsion a zombie film, but there are some interesting choices on Polanski’s part that suggest that we can identify with Carol not merely as than an unreliable narrator, but as the heroine of this story, the lone survivor navigating through a very hostile environment. For one thing, the way he sketches out Carol’s surroundings – in this case, swinging sixties London – evokes a sex-obsessed landscape where there is no way for her to escape that which disgusts her the most – sex and men. Carol, it seems, is the only one of her kind, surrounded by people who have totally different value systems. She is functional, for the most part, in situations where sex and the relationships that call for them don’t exist. But even a moment of friendship between a coworker turns from fits of girlish giggles to sullen silence the minute the coworker mentions a boyfriend. We know now that being averse to or disinterested in sex does not make one disturbed – asexuality is alive and well in twenty-first century notions of sexual preference – but in a time where such an option doesn’t exist, where one is forced into a mold that is ill-fitting as best, horrific at worse…well, that’s a constant oppression that we watch Carol experience.

That isn’t to say that Carol isn’t disturbed. As the withdrawn, mouse-quiet manicurist, Deneuve imbues her character with the hushed apprehension of someone who is sitting two inches from a hot flame. However, her fear, her murderous impulses don’t exist in a vacuum. She is traumatized for sure and while there is much speculation as to why (certainly Polanski himself won’t explain. “Don’t ever ask me to explain to any of my pictures,” he says in A British Horror Film, a making-of included on the Criterion release), I think it is pretty clear : she is surrounded by monsters. Polanski has populated Carol’s world with grotesque caricatures acting as her neighbours, her suitors, her clients at the beauty salon. Even her sister, played by Yvonne Furneaux, is the kind of highly-sexed, uncaring person who doesn’t understand Carol at all, who brandishes her illicit romance and invites the enemy – in this case, her married boyfriend – into their home. At the end, when Carol finally goes into a complete state of shock, her neighbours gape at her dumbly, wondering how a nice girl like her could’ve gone so far astray. What they don’t realize is that they were the ones she’s been fighting all along.

That isn’t to say that Carol isn’t disturbed. As the withdrawn, mouse-quiet manicurist, Deneuve imbues her character with the hushed apprehension of someone who is sitting two inches from a hot flame. However, her fear, her murderous impulses don’t exist in a vacuum. She is traumatized for sure and while there is much speculation as to why (certainly Polanski himself won’t explain. “Don’t ever ask me to explain to any of my pictures,” he says in A British Horror Film, a making-of included on the Criterion release), I think it is pretty clear : she is surrounded by monsters. Polanski has populated Carol’s world with grotesque caricatures acting as her neighbours, her suitors, her clients at the beauty salon. Even her sister, played by Yvonne Furneaux, is the kind of highly-sexed, uncaring person who doesn’t understand Carol at all, who brandishes her illicit romance and invites the enemy – in this case, her married boyfriend – into their home. At the end, when Carol finally goes into a complete state of shock, her neighbours gape at her dumbly, wondering how a nice girl like her could’ve gone so far astray. What they don’t realize is that they were the ones she’s been fighting all along.

That leaves us with the final image, the only thing Polanski gives his audience that resembles a clue: a photograph of Carol’s family, with a younger Carol standing aloof, her expression impassive and cool. What does it mean? Was she abused? What happened when she was younger? Instead of viewing it as a probe into something deeper, I see the image as a summary of what we’ve just witnessed: a girl, a child really, standing alone among others, trapped in beliefs and fears that no one understands.

– Lena Duong

Visit the Criterion Collection website