On February 1st, Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist Art Spiegelman held court at the prestigious, private liberal arts school University of Richmond and attempted to answer the question, “What the @#% happened to comics?” at an institution, which doesn’t have a class that teaches comics. He characterized comics as the main front of a battle between the “genteel and vulgar” and traced out their history from Rodolphe Topffer’s The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck in 1842 to innovative works by creators, such as Chris Ware. Along the way, he threw shade on the superhero genre (except for Jack Cole’s Plastic Man) and digital comics, extolled the satire and self-reflexiveness of MAD, which helped him acclimate to American culture as a son of immigrants, and dug deep into what makes comics a unique and powerful medium.

Spiegelman began his lecture by throwing out some numbers and giving a “basic” overview of the history of comics. He said that there were 15 million comics readers a week, but then they were heavily censored after World War II and became stereotypically the province of nerds and children until the rise of the “graphic novel” of which Spiegelman’s Maus, is considered one of the first. Even though, he never set out to write a “graphic novel”, but just a comic for adults that needed a bookmark and could be reread. He said comics are powerful because they work in icons and go past the critical radar immediately to your brain and defined art as “what gives from to  thought and emotion”. Then, Spiegelman performed a biting critique of artist Roy Lichtenstein, whose blowing up of comics panels in paintings, was a comment on the banality of representation and did no more for comics than Andy Warhol did for soup.

thought and emotion”. Then, Spiegelman performed a biting critique of artist Roy Lichtenstein, whose blowing up of comics panels in paintings, was a comment on the banality of representation and did no more for comics than Andy Warhol did for soup.

This critique segued into a discussion about comics as a narrative, and Spiegelman did close readings of a couplepages from his works, Maus and In the Shadow of No Towers. It was exciting to get an insight into how a cartoonist manipulates the comics page to create meaning. For example, in Maus, Spiegelman created a dinner table space to introduce the various members of his dad’s family as a whole and made window-like panels to introduce each individual. Who said exposition and character establishment has to be tiresome? With In the Shadow of No Towers, his 2002 collection of short comics about 9/11, Spiegelman used a more non-traditional panel layout with different strips littered across the page to show how he and the United States were disoriented after 9/11, which is when he got a call to pick up his daughter from school near Ground Zero.

Spiegelman then went further into comics theory and said that comics were time turned into space, and how some of the minimalist comic strips of Jules Feiffer used beat panels to get its comedic timing correct, like one about a man and his wife having sex that was only words, black panels, and one line for the man and woman. After saying the R. Crumb adage that comics are “only lines on a page” and referencing the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists, who were killed for satirizing the prophet Muhammad (Frankly, in a racist way.) , he talked about how propagandists use stereotypes in comics and cartoons to dehumanize their opponents. For example, Nazi Germany portrayed Jewish people as rats in propaganda, and likewise in American propaganda, Germans were portrayed as bats and the Japanese as rats. Spiegelman himself came under fire in 1993 for drawing a Hasidic Jewish man kissing an African-American woman on the cover of the Valentine’s Day issue of New Yorker to draw attention to the Crown Heights race riots. This was an abstract drawing rooted in the context of the time, but it was criticized for the way the Jewish man’s lips were drawn or the fact that he looked like a sexual predator. One New York Times reader thought the cover was Abraham Lincoln kissing a slave.

Spiegelman then went further into comics theory and said that comics were time turned into space, and how some of the minimalist comic strips of Jules Feiffer used beat panels to get its comedic timing correct, like one about a man and his wife having sex that was only words, black panels, and one line for the man and woman. After saying the R. Crumb adage that comics are “only lines on a page” and referencing the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists, who were killed for satirizing the prophet Muhammad (Frankly, in a racist way.) , he talked about how propagandists use stereotypes in comics and cartoons to dehumanize their opponents. For example, Nazi Germany portrayed Jewish people as rats in propaganda, and likewise in American propaganda, Germans were portrayed as bats and the Japanese as rats. Spiegelman himself came under fire in 1993 for drawing a Hasidic Jewish man kissing an African-American woman on the cover of the Valentine’s Day issue of New Yorker to draw attention to the Crown Heights race riots. This was an abstract drawing rooted in the context of the time, but it was criticized for the way the Jewish man’s lips were drawn or the fact that he looked like a sexual predator. One New York Times reader thought the cover was Abraham Lincoln kissing a slave.

After this political interlude, Spiegelman delved into the history of comics starting with newspaper comic strips, who he called the “bastard offspring of art and commerce”. Originally, Joseph Pulitzer was going to publish an “art” section in his papers that replicated famous paintings, but the coloring process didn’t work and it was replaced with a humor comics section instead. In an age where television was black and white and radio was just coming into its own, Spiegelman likened the four color comics strips to “virtual reality glasses”. The early comic strips, like The Yellow Kid, were influenced by slapstick comedy and vaudeville, and was considered vulgar by some newspapers. And thus comic strips became a battle between the “genteel and vulgar” with the suburban-set art deco fantasies of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo set against the slum alley setting of The Yellow Kid. Spiegelman compared comic strips being accepted as an art form with Little Nemo to the evolution of jazz from music played in brothels to George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue.

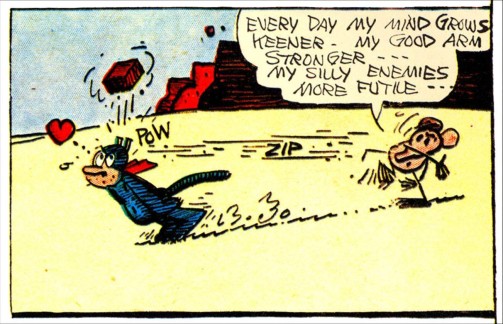

Then, Spiegelman talked about some other influential comic strips, like George Herriman’s surreal Krazy Kat about a love triangle between a cat, dog, and mouse, who throws bricks at the cat. Its simplicity and its country twang style of writing have allowed many critics to project all kinds of psychological and political allegories on it. Next, Spiegelman waxed poetic about Dick Tracy, which brought the violence of the front page to the funny pages, and he compared it to The Sopranos. He praised its diagrammatic panel grids, which have been an important of comics ever since, and how in his later years, the strip’s creator Chester Gould went experimental and took the comic to the moon. Finally, Spiegelman talked about how the blank eyes of Little Orphan Annie‘s character made it easier for people to connect emotionally with the characters, which is why he borrowed this eye style for Maus, and how he didn’t connect to Peanuts because the Republican girls read it, but how the alienation of Charlie Brown had a big effect on comics creators, like Daniel Clowes (Ghost World) and Chris Ware (Building Stories). But when he met Charles Schulz, Spiegelman said that he was knowledgeable about the medium, especially in how to tell a short story with a punchline, and that he didn’t use an assistant even when he was getting older and his lines were more jagged and not straight.

Finally, Art Spiegelman turned to comic books, which began as reprints of comic strips and then solicited new ideas from anyone to fill up space, including two Jewish boys from Cleveland named Joe Siegel and Jerry Shuster, who created Superman in Action Comics #1. Spiegelman say he didn’t care much for superhero comics after his childhood poking fun at a Silver Age Superboy comic, but occasionally enjoyed “weird” superheroes like Stardust the Superwizard, whose comic was filled with lines of energy and had OCD. He also talked about how Jack Cole’s Plastic Man stories where the titular character had the power to turn into anything (Basically, the power of comics.), including abstract art paintings and laundry baskets to catch crooks were his gateway drug to Mad, Spiegelman’s biggest influence, which instilled a love of parody and irony him. He said that Mad helped Americans survive the 1950s and led to all kinds of pop culture satire from The Simpsons to The Daily Show becoming a pop culture phenomenon that is still found on newsstands today after humble beginnings as a one page backup in the various horror comics published by EC under the legendary Harvey Kurtzman. Spiegelman observed that EC’s horror comics were the secular Jewish response to the Holocaust while their sci-fi comics, like Weird Science, were the same to the atom bomb.

from anyone to fill up space, including two Jewish boys from Cleveland named Joe Siegel and Jerry Shuster, who created Superman in Action Comics #1. Spiegelman say he didn’t care much for superhero comics after his childhood poking fun at a Silver Age Superboy comic, but occasionally enjoyed “weird” superheroes like Stardust the Superwizard, whose comic was filled with lines of energy and had OCD. He also talked about how Jack Cole’s Plastic Man stories where the titular character had the power to turn into anything (Basically, the power of comics.), including abstract art paintings and laundry baskets to catch crooks were his gateway drug to Mad, Spiegelman’s biggest influence, which instilled a love of parody and irony him. He said that Mad helped Americans survive the 1950s and led to all kinds of pop culture satire from The Simpsons to The Daily Show becoming a pop culture phenomenon that is still found on newsstands today after humble beginnings as a one page backup in the various horror comics published by EC under the legendary Harvey Kurtzman. Spiegelman observed that EC’s horror comics were the secular Jewish response to the Holocaust while their sci-fi comics, like Weird Science, were the same to the atom bomb.

These horror comics and some “subtextual” observations of various superhero comics led to Frederic Wertham writing the book Seduction of the Innocent that led to the Comic Code Authority and heavy censorship of the medium, which only left room for superhero and kids comics until the rise of underground comics. Spiegelman joked that the index of “bad comics” at the end of Seduction of the Innocent acted as a reading guide to him in his early years, and he skipped over the fresh, bombastic storytelling of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko’s early Marvel Comics straight to underground comics, which he said he were influenced by the subtle humor of funny animal comics like Donald Duck. These comics pioneered by R. Crumb were sold in limited print runs at head shops, sometimes featured funny animals, and had more adult content. They also weren’t constrained by the need for punchlines, which led to new genres, like the confessional autobiography. The first one of those was Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972) by Justin Green, and Spiegelman himself published the “Ur-Maus” in a three page story in Funny Aminals about his father’s experience in the Holocaust. (I sadly noted the absence of autobiographical comics classic American Splendor by Harvey Pekar.)

The talk stopped being a history lecture for a minute as Spiegelman talked about his own underground comics anthology Raw that he did with his wife Francois Mouly, which combined autobiographical and experimental formats as a “comic book for intellectuals” and serialized the chapters of Maus before it was published as a “graphic novel” in 1986, the same year Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns were released. Spiegelman then skipped over the “British Invasion” of the late 1980s and early 1990s, which led to classics like Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles, and Warren Ellis’ Transmetropolitan and extolled some of his favorite comics creators of the 2000s, like the innovator of the comics page Chris Ware and his Building Stories, Charles Burns’ Black Hole, a body fear story which made Lichtenstein look like a fraud, and others to numerous to count. He also mentioned that some of the best comics in the 21st century were made by women, like Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Lynda Barry’s What It Is. Spiegelman’s final remarks about comics in general before promoting his own work was about how digital comics weren’t as immersive as physical comics, which you could reflect on versus clicking from screen to screen. As someone who is an avid reader of digital comics (and most of my reviews are of digital copies), this is definitely just a preference. It is also easier to buy a few books on Comixology or the Amazon Kindle Store with a single click than find a comic book store.

The talk stopped being a history lecture for a minute as Spiegelman talked about his own underground comics anthology Raw that he did with his wife Francois Mouly, which combined autobiographical and experimental formats as a “comic book for intellectuals” and serialized the chapters of Maus before it was published as a “graphic novel” in 1986, the same year Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns were released. Spiegelman then skipped over the “British Invasion” of the late 1980s and early 1990s, which led to classics like Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles, and Warren Ellis’ Transmetropolitan and extolled some of his favorite comics creators of the 2000s, like the innovator of the comics page Chris Ware and his Building Stories, Charles Burns’ Black Hole, a body fear story which made Lichtenstein look like a fraud, and others to numerous to count. He also mentioned that some of the best comics in the 21st century were made by women, like Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Lynda Barry’s What It Is. Spiegelman’s final remarks about comics in general before promoting his own work was about how digital comics weren’t as immersive as physical comics, which you could reflect on versus clicking from screen to screen. As someone who is an avid reader of digital comics (and most of my reviews are of digital copies), this is definitely just a preference. It is also easier to buy a few books on Comixology or the Amazon Kindle Store with a single click than find a comic book store.

Art Spiegelman’s talk “What the @#$% Happened to Comics” was filled with insight about the formal qualities of comics, and how different storytelling techniques create different emotions on the comics page. Even though he neglected bande desinee, manga, and most non-American comics (Except for the early pioneering work of Swiss cartoonist Rodolphe Topffer.), Spiegelman provided a glimpse into how certain comics, like funny animal books, Mad, various comic strips, and underground comics, influenced his own work on Maus, Raw, and his most recent project Wordless!, a stage show showing woodcuts in sequence to a jazz score. It was a journey through comics through his eyes, and Mr. Spiegelman wasn’t a half bad tour guide.