Heaven and earth are ruthless

And treat the myriad creatures as straw dogs;

The sage is ruthless

And treats the people as straw dogs

The Cahiers du Cinema called it “the furious springtime of world cinema,” and nowhere was it more furious than in the United States.

From the 1960s through the 1970s, a confluence of events sociological and cultural combined with sea changes in the motion picture industry to ignite one of the most creatively combustive periods in American commercial filmmaking. All the shouldn’ts, and couldn’ts, can’ts and don’ts of studio moviemaking established over decades by the Hollywood establishment were now being bent, twisted, and inverted when not being plainly shoved aside or steam rollered. What had been taboo had now become the backbone of the trade, and there was hardly a social hot button of the time – sexuality, homosexuality, the division between young and old, Vietnam, government malfeasance, ageism, feminism, racism, the nuclear threat, etc. – that didn’t, sooner or later, find itself thrown on the big screen and often tackled with a brutal frankness. This was the era of Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Little Big Man (1970), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Being There (1979), Badlands (1973), Raging Bull (1980), The Conversation (1974), The Killing of Sister George (1968), Joe (1969), Bonnie and Clyde (1967), M*A*S*H (1972), Midnight Cowboy (1969), Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), Point Blank (1967), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Apocalypse Now (1979), Taxi Driver (1976), Network (1976), The Godfather (1972), Nashville (1975), Last Tango in Paris (1972), Deliverance (1972), Chinatown (1974)… The list of memorable and landmark movies from the time goes on and on, staggering in both its length and breadth.

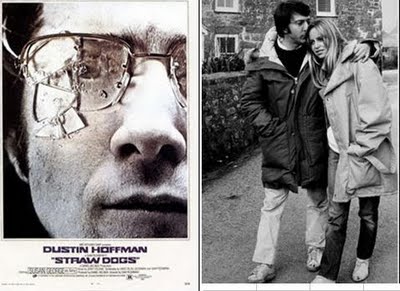

Notable among the notable was 1971’s Straw Dogs. Appropriately enough, one of the most provocative movies from that time was directed and co-written by one of the most controversial filmmakers of that time: Sam Peckinpah.

Peckinpah had already single-handedly escalated the then ever-growing, ever more heated debate over film violence with his blood-drenched 1969 revisionist Western, The Wild Bunch. Straw Dogs would become an even more polarizing film…and also the director’s biggest commercial success up to that time.

The film’s screenplay was adapted from a 1969 novel by Scottish author Gordon Williams: The Siege of Trencher’s Farm. It says something about the impact of the movie – and the way it continues to reverberate among serious cineastes – that the most recent reprint from Titan Books, published this year to capitalize on a remake of Peckinpah’s film to be released this fall, is billed as (in small print), The Siege of Trencher’s Farm: The Novel that Inspired (in print twice as big) Straw Dogs.

The film’s screenplay was adapted from a 1969 novel by Scottish author Gordon Williams: The Siege of Trencher’s Farm. It says something about the impact of the movie – and the way it continues to reverberate among serious cineastes – that the most recent reprint from Titan Books, published this year to capitalize on a remake of Peckinpah’s film to be released this fall, is billed as (in small print), The Siege of Trencher’s Farm: The Novel that Inspired (in print twice as big) Straw Dogs.

While Williams no doubt appreciates how the endless notoriety of the film has brought him years of continued royalties on a book which most probably would have disappeared — as most do — within a few years of its first publication, the fact is Williams hated Peckinpah’s film. Hated it. Called it “horrific” at the time of its release, claiming he would “….never again sell one of my books to an American.” According to one 2003 interview conducted in conjunction with the UK video release of Straw Dogs, it seemed Williams still hated the movie 30 years later, flatly declaring it “crap.”

And from the few peeks so far offered of writer/director/producer Rod Lurie’s upcoming remake, it’s a good bet Williams will hate that film, too. Hate it.

- * * * *

Born in Paisley, Scotland in 1934, Williams had bounced around the provinces for some years as a journalist, but by the late 1960s, he was shaping up as a rising figure on the UK literary scene. Paramount had paid him big money for his novel, The Man Who Had Power Over Women (released in 1970 starring Rod Taylor), and his next book, the 1968 work From Scenes Like These, a grim picture of working class life in late 1950s rural Scotland, had been shortlisted for the inaugural awarding of the Booker Prize the following year (P. H. Newby’s Something to Answer For would ultimately receive the prize).

The Paramount money underwrote a move by Williams and his family to Devon, a largely rural county in southwest England. Devon also happened to be home to famed Dartmoor Prison. Williams put the brooding presence of Dartmoor together with stories about escaped British gangland killer and certified psycho Frank “The Mad Axeman” Mitchell (it was later learned Mitchell hadn’t escaped but been kidnapped and murdered by some of his underworld associates), and started coming up with the cornerstone elements of his next novel: an escaped lunatic, a band of vigilantes, an isolated farmhouse, and the idea of turning “…a group of ordinary people…into murderers by eight o’clock tomorrow morning.”

According to Williams’ 2003 interview for The Guardian, he intended the book as nothing more than “…a hit-and-run cheap paperback,” banging it out in a startlingly short nine days.

The resultant work – The Seige of Trencher’s Farm — is a consequently schizophrenic work, showing, at times, the same strong, lyrical prose which had earned Williams a contender’s spot for the Booker bumping up against the kind of awkward storytelling one might expect from a quickly ground out potboiler hung on an intriguing hook but an undercooked narrative. It is a novel both overly complicated yet simplistic; by turns sluggish and pulse-pounding; at times hot-blooded, yet clumsily contrived, sometimes to the point of corny melodrama.

George Magruder is an American academic working on a book about 19th century English literary footnote Branksheer. His homesick English-born wife of nine years, Louise, has persuaded him to spend his writing sabbatical back in her home country. Along with their daughter Karen, they take a house in the rural west country of England.

This is a marriage already in trouble. Back in the States, faced with George’s disciplined emotions and growing sexual inattention, Louise had drifted into a fling with a visiting English poet, a sore spot George does not hesitate to poke during their frequent squabbles. Too many years together and now cooped up in their rented farmhouse, having only modest contact with the insular villagers nearby, the quirks and minor irritations they had once tolerated in each other now set off regular shouting matches. Here on her native soil, Louise has come to realize just how out of place she had been back in the States – and how George is even more out of place in England.

Driving home through a blowing snowstorm from a church-sponsored Christmas party for the parish children one night, George accidentally hits a figure wandering across the road. It turns out to be Henry Niles, a mental patient escaped from an ambulance when the vehicle crashed on the icy roads. Although years of imprisonment and illness have left Niles a hapless figure, he remains the village boogey man, always spoken of with a mix of fear and distaste having been locked up in the nearby asylum for molesting and killing three children.

George takes the injured Niles home unaware that, at that moment, the villagers are looking for a missing young girl, some of them positive she’s fallen victim to the escaped Niles. When word reaches the girl’s father that Magruder has Niles at his house, he and some of his less than savory pub mates trek out to the Magruder house and demand George turn over Niles. Already resenting the Magruders as outsiders, and – by the village’s threadbare standards – affluence, their liquor-stoked vigilantism leaves them in no mood for reasoned argument. The stakes tragically escalate to all-or-nothing when one of George’s well-meaning neighbors is accidentally killed by one of the men while trying to talk them into going home.

Cut off from escape by the snow, their phone line severed by the small mob outside, George realizes – as do the men – that the vigilantes’ only option for avoiding punishment for the killing is to murder the family of witnesses inside the house. At first, George’s defense of the house is an analytical process of problem-solving, but as the mob begins to get inside his walls, the fighting becomes increasingly brutal and mindlessly savage. By daybreak, George stands triumphant, having beaten three of the invaders senseless, caused another to inadvertently shoot off his own toes, and gouging out the eyes of the last:

“He had won! That mattered, nothing else…He felt tired. And proud. The greatest feeling in the world…To know you could stand up to anything in the world. To know you were a man, to be able to feel it in your guts.”

Louise, who had reached a point in their marriage where she’d come to think little of her husband as a man, and had wanted him to give Niles up, now recants her disparagements, her affair, her disappointments: “I don’t deserve you, George, it’s true, I don’t, I don’t…” And with that, the family is, again, whole.

The feeling one gets reading The Siege of Trencher’s Farm is of Williams having this terrific idea of the eponymous siege (which takes up well over half the novel) and of turning his innocuous villagers and bookish academic “…into murderers by eight o’clock tomorrow morning,” but then of having to quickly slap together some kind of functional set-up in order to get to the good stuff. It almost feels as if he worked backward, starting with the siege and then figuring, “Well, to end up there, this has to happen; and to get there, this has to happen,” and continuing on back to the beginning, giving the story more of an obviously constructed (or contrived, depending on how ungenerous you feel) vibe rather than that of a naturally flowing arc.

Even the idea of the Magruders coming to this far-off bit of England is a forced construct. Louise’s feeling of homesickness makes sense, but why this cosmopolitan Londoner already suffering marital doubts would push to settle in such an isolated, impoverished part of the country far from everything she knows – including her own family — hardly seems the solution to her problems. The couple fight because Williams needs them to fight; because they can’t make up at the end of the book unless they fight; and so they claw and spit at each other at the slightest provocation, each fight quickly going nuclear.

Too much of the book is built around such “has to”’s. Niles’ escape hangs on the hoariest of clichés; a distracted driver in a rush, a snowstorm, slippery roads. And later, during the siege, while George still has a working phone, the ill-fated good neighbor calls about stopping by but it never occurs to George to use the phone to tell the police there’s an angry mob outside his house looking to lynch Henry Niles. Things happen because Williams needs them to happen to ignite his rousing third act; not because they would naturally happen, or even make sense.

Williams sets the events of the story within what should be a pressure cooker of a 24-hour framework, but until the siege begins, the story never works up much momentum. Instead, the compressed time frame forces Williams to keep interrupting the forward flow of the plot to make regular installments of backstory to justify the actions of not only George and Louise, but nearly every integral character in the book – as well as a good number of peripheral characters (the minister putting together the Christmas children’s party; the bartender at the local inn; the cops trekking overland through the snowstorm to bring in Niles; etc.)

That kind of omniscient, ensemble approach probably worked fine for a portraiture like From Scenes Like This, but here, for much of Seige’s first act, it leaves the book feeling unfocused, inchoate, the stop-start-stop-start rhythm of the plot regularly halting for more backstory turning the first 90 pages into a slog.

It doesn’t help that Williams’ dialogue is flat and colorless and often heavy-handedly expository, even when the characters are at their most heated (nor does George’s “Americanese” sound particularly American). Consider this spat between George and Louise early in the book. Christmas is coming up and Louise asks George to put his work aside to join in with Karen and herself wrapping gifts. George says no, Louise presses, and soon the argument starts sounding like bad soap opera dialogue. After Louise refers to George as a “so-called professor,” George immediately sends off his nukes:

“A so-called professor! That’s better than being a so-called poet. I suppose you’re just eating your heart out for that fat slob.”

“Are you referring to Patrick Ryman? If so, I — ”

“Who else would I be referring to? That’s why you wanted us to come to this precious little country of yours, isn’t it? Romantic fantasy. Did you think he’d come riding up the lane and carry you off? Come to England, I want to show you my country! Horseshit! All you wanted was to indulge some sordid little romantic daydream.”

“Oh, clever, clever. You found another word for fantasy, you’re improving.”

When we meet George and Louise at the beginning of the book, Williams doesn’t give us much to connect with. They’re already sniping at each other, there’s no sense of some happier past, and there’s little more to them than Louise being something of an unhappy bitch and George a spiteful tight-ass.

But if Williams seems to stumble through the book’s first act, the book does begin to jell once the siege begins, gaining intensity with its narrowing focus, and accelerating as the fight for the house becomes more desperate. By the climax of the siege, with George in a frantic hand-to-hand grapple with one of the home invaders, the book is in a roaring third gear and almost glowing with the heat of animal rage.

It is times like that – and they happen off and on throughout the book – when one sees the novel The Siege of Trencher’s Farm might have been; reminded, then, that it was not for nothing Williams had been a Booker contender. One of the best sections of the novel is the opening chapter which today’s editors, mindful of an ADD just-get-on-with-it audience sensibility, would probably have told Williams to cut. It doesn’t serve the plot, it doesn’t serve the characters. And yet, it is the book’s keystone, making so much of what follows understandable (and much of Williams’ exposition redundant):

“In the same year that Man first flew to the Moon and the last American soldier left Vietnam there were still corners of England where lived men and women who had never travelled more than fifteen miles from their own homes. They had spent all their lives on the same land that had supported their fathers and grandfathers and great-grandfathers and unknown generations before that.”

For the next several pages, Williams paints a bleakly lyrical picture of this insular, impoverished, inward-turned rural backwater, a place isolated as much by ignorance and suspicion of outsiders and their world as by the surrounding hills and easily choked off narrow unpaved roads. It is a place tragically mired in its own dark history, with a longstanding, long instilled sense of ritual loyalty to “our own” trumping any moral judgment or transgression. For those few pages, Williams seems on the verge of pulling off an English version of James Dickey’s Deliverance (published two years later). But he only comes close to Dickey’s eloquence intermittently, and never attains the same haunting soulfulness. Where Dickey lets his more existential themes bubble along as subtext, Williams clubs the reader with the obvious in case it was somehow missed among all the eye-gougings and beatings: “Now he knew the truth. All that nonsense about thresholds and civilization.”

Williams delivers a book which is ultimately cathartically entertaining, but not particularly compelling or insightful.

Unlike Williams, Sam Peckinpah had more on his mind than a “hit-and-run” quickie thriller. But then he almost always did.

As happened on disturbingly regular occasions, Sam Peckinpah’s career was – yet again – at a problematic point at the beginning of the 1970s.

In 1961, Peckinpah graduated from a successful TV career to the big screen directing the neatly done but little noticed Western The Deadly Companions. He followed this in 1962 with what was instantly declared a newly-minted Western classic, Ride the High Country. In 1964, Peckinpah tackled the more epic-scaled cavalry adventure, Major Dundee, but the film fell victim to last minute budget cuts, clashes between Peckinpah and his producers, and arguably Peckinpah’s own limitations in handling his first grand scale production. Dundee was an expensive commercial and critical flop, and after being fired from his next project — The Cincinnati Kid – just a few days into shooting, Peckinpah was tacitly blacklisted as a feature director (Norman Jewison would complete the 1965 feature).

In his few short years as a feature director, Peckinpah had well earned a reputation for being combative, rebellious, paranoid, regularly stoking his demons with constant heavy drinking. He had fought – bitterly — with his producers on all of his feature film projects. Those years left him labeled with that most toxic of Hollywood descriptives – “difficult” – and he was considered unemployable.

But Peckinpah came back, first in a 1966 return to TV to write and adapt an award-winning version of Katherine Porter’s short story, “Noon Wine,” for producer Daniel Melnick. Peckinpah’s big screen resurrection came in 1969 with another Western classic and one of the seminal films of the 1960s/1970s, the apocalyptic The Wild Bunch. Trying to demonstrate he was more than just an action director, Peckinpah followed Bunch with the elegiac The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), but even before the film was finished, Peckinpah was fighting with the very same Warner Bros. execs of whom he’d been so complimentary during the production of Bunch. The blowback was that while Hogue was a critic’s darling, Warners gave the film only the most minimal release and it quickly disappeared.

Marshall Fine, in his biography Bloody Sam: The Life and Films of Sam Peckinpah, tells of Peckinpah casting about after Hogue for an opportunity to break out of the action/Western director mold he felt he was being funneled into, but having little luck generating any studio interest in his non-Western/non-actioner projects (ironically, one project Peckinpah had wanted in on was the film adaptation of Deliverance which went to John Boorman). Then his old “Noon Wine” associate, Daniel Melnick, making his first stab at producing a feature, called Peckinpah about a project he’d been developing with his partner, David Susskind, based on a novel Susskind had bought called, The Siege of Trencher’s Farm.

According to Fine, Peckinpah had been playing around for years with ideas inspired by his reading of sociological anthropologist Robert Ardrey’s books on the instinctive violence he saw still residing somewhere within civilized men. In Siege, Peckinpah saw a vehicle to put those concepts into play. Though the story climaxed with the brutal farmhouse battle, much of the story was drama-driven and would thus stand apart from his previous work. The project also provided Peckinpah with his first feature opportunity to demonstrate his skill with contemporary material set far away from the Old West with which he had come to be identified.

By the time Peckinpah was brought on, the project had already been through the hands of several screenwriters with no success at nailing down Williams’ story for the screen. Melnick hired screenwriter David Zelag Goodman (previous credits included cult Western Monte Walsh, and bittersweet rom-com Lovers and Other Strangers [both 1970]), and he and Peckinpah would continue to work on the script all the way through production (although other writers would also contribute to the screenplay, Goodman and Peckinpah are the credited writers).

One of the numerous changes they made to Williams’ novel was replacing his long-winded title. Walter Kelley, an acquaintance from Peckinpah’s TV days who would become one of the director’s regular uncredited collaborators, gave Peckinpah a quote by the Chinese philosopher Lao-tse which would provide the new title: Straw Dogs. It was possibly the only change in the source material Williams liked, the author telling e-zine iofilm in the early 2000s, “It’s obviously memorable.”

Whereas Williams had produced a plot complicated in its construction but simplistic in its dramatic heft, Peckinpah, Goodman, et al greatly simplified the construction to produce a more dramatically complex narrative. The screenplay does away with Williams’ 24-hour framework, giving the story the breathing room to gradually open up over a much more extensive period without having to jam in a lot of justifying backstory. The film starts with the couple – childless and now renamed David and Amy Sumner – having only recently moved into Trencher’s farm. Unlike the novel, they begin as a reasonably happy couple, their relationship only deteriorating bit by bit over time as the dramatic stresses of the story slowly ratchet up.

Key to the film’s set-up – and a vast improvement over the book – is awarding both Amy and David compelling reasons for settling in the English backcountry. For Amy (Susan George) – presented here as both younger and, one senses, more attractive than Louise – this is a triumphant return home. It’s not hard to see that, back in the States, Amy must have been considered something of a trophy wife for the bespectacled, dweebish David (Dustin Hoffman). By the same token, David is a trophy husband, socially and intellectually head and shoulders above the boorish, ignorant villagers. Amy is here with David in tow to showboat how far she’s come since leaving her little backward hometown.

Her return comes with a complication: old boyfriend Charlie Venner (Del Henney). It’s clear from the outset that while Amy has somewhat boastfully moved on, the feelings on Venner’s end are more unresolved. Or perhaps, following through on Robert Ardrey’s theses, Venner’s feelings are more primal, territorial; Amy was mine and that makes her mine always.

David is not a literary researcher, but something even more arcane: an astromathematician, someone with his mind literally in the clouds which only emphasizes how inept he is at handling terrestrial affairs. David’s reasons for the move to England are anchored in a subtext which probably eludes contemporary audiences, but viewers in 1971 well understood.

From the late 1960s on, American college campuses had become something of a social battleground. Student protests – some of them violent – over the Vietnam war, and subsequently other social issues as well, had become a regular feature on the nightly news. Students clashed with police, with older blue collar counter-protestors, ROTC buildings were burned and bombed, administration buildings were occupied and campuses shut down. Student unrest reached an emotional peak in May 1970 with the killing of four students and wounding of nine others by National Guardsmen called in to break up a protest on Ohio’s Kent State University campus sparked by the expansion of the war into Cambodia.

Williams’ book is criminally oblivious to the state of campus affairs at the time, but it’s critical to the film’s David. He has come to this empty corner of the world — Amy at one point accuses him — “because there’s no place left to hide.” Later in the film, as he and Amy begin to go at each other, she calls him out on this very point when he tries to hide behind his work, telling him he’d come to England not to noodle formulae in peace, but “…because you didn’t want to take a stand!”

This, then, becomes the foundation on which the rest of the film’s narrative is built; a marriage probably built less on true love than on passion and ego, one not-quite-mature partner coming home to display her catch, the other to hide from a society demanding commitment and confrontation. In her notes for a Peckinpah film festival sponsored by Lincoln Center, critic Kathleen Murphy nails the character of the Sumners as that of “…children playing at life.”

Showing he’s a good sport, David hires Venner and his pub cronies to repair the roof on his garage. When Amy complains about some of the comments the men make as she passes by, the confrontation-avoidant David blows it off as good-natured wise-cracking. The men grow more lackadaisical in their work, their opinion of the mousey American dwindling by the day.

In the book, George finds the family cat strangled out on the grounds, Williams portraying the killing as a simple act of random violence; part of the dark nature of the country. In Straw Dogs, David and Amy find their cat strangled and hanging in their bedroom closet, nothing random about it. Amy wants David to confront the men working on the garage, certain one of them is responsible. David waffles, claiming they can’t know that for sure, and, besides, why would they do it?

“To prove to you that they could get into your bedroom!”

Easily the most controversial change the film makes from the book – and one of the elements Williams most despised – was the rape of Amy. Williams was outraged, and feminists and some critics – and particularly feminist critics like Molly Haskell — declared Peckinpah a misogynist indulging in the macho fantasy that women enjoy rape.

The oblivious David takes Venner and his mates up on their invitation to join them on a “snipe hunt.” Leaving David abandoned on the moor, Venner sneaks back to the farmhouse to – in Ardrey fashion – take back what’s his: Amy. When he tries to force himself on her, she resists and Venner strikes her a blow that floors her. She only surrenders herself when Venner threatens a second blow. But what at first begins as a violation begins to change and at a certain point Amy begins to respond. She has grown apart from her husband, old feelings of communion are stirred up by her ex, and just as Venner and his mates have judged David not up to their primal standards of masculinity, so, too Amy has come to the same view.

Now, how much true-to-life psychological validity this has is certainly up for debate, but within the context of the film’s narrative, it makes a sad sense.

But the scene doesn’t end there, and what follows should have (but didn’t) put a stake through the breastbone of the macho-rape-fantasy view. Afterward, Venner looks up to see one of his mates – Scutt (Ken Hutchison) – is holding a shotgun on him, beckoning him to move away from Amy so he can take his turn. Venner shakes his head, but the muzzle of the shotgun wins the argument. Amy doesn’t know what’s happening until Scutt turns her round to take her from behind. Venner – in a warped display of tribal male loyalty – holds Amy down for Scutt, even though his distaste is obvious.

This time, there is no transformation of the act from violation to revived passion. It’s a brutal, animalistic act leaving Amy emotionally scarred.

She cannot confess the true rape to David without confessing the not-quite-rape by her onetime lover, and so David returns from the moor seeming all the more petty in his pissing and moaning about “your (Amy’s) friends,” completely insensitive to the obvious fact something’s amiss with his wife. Besides, by this time Amy has come to view David as a coward: what could he possibly do about it?

Later, at the church talent show, Amy is tormented by the leering looks from Scutt and the mates with whom he’s no doubt shared the story of his triumph. The trauma of his attack comes back to her in disturbing flash cuts. She asks David to take her home and that’s when David strikes Henry Niles (David Warner) with his car.

Henry Niles’ part in the film has also been streamlined from the novel. He’s a simple-minded fellow – think Of Mice and Men’s Lenny — living with his brother in the village, and though some allusion is made to past acts and warnings are made to Niles’ brother to keep Henry away from the local children, he is no murderer, and there is no melodramatic escape from his asylum keepers.

Williams goes into the siege portion of the novel having laid out clear moral divisions between attackers and defenders, and by the end of the book he’s kinda/sorta cheated to keep them that way. Williams’ Niles has killed in the past, but this time he’s innocent, the missing child having simply wandered off and become lost in the snowstorm (and later found). Williams even adds the unnecessary wrinkle that George and Louise had participated in an anti-death penalty protest years earlier to save Niles from hanging during the last days of England’s capital punishment. George’s defense of his house first begins on the elevated principal of protecting the helpless and innocent Niles. Then later, when it becomes a more primal matter of survival, there’s still a heroic quality to George’s stand since it’s not only his and his wife’s life he’s trying to preserve, but also that of his eight-year-old daughter. And, despite the brutality George falls back on to fend off the invaders, none of them die at his hands, preserving George’s position on the moral high ground.

But Peckinpah was a filmmaker who gloried in moral ambivalence. The hero of Major Dundee is a soldier with an Ahab-sized obsession who nearly destroys his command trying to justify his own opinion of himself by chasing after an Apache raider; the men of The Wild Bunch are ruthless, robbing killers who gain our sympathy only because they are less reprehensible than the ragtag posse chasing after them.

In the movie, no young, mentally afflicted girl wanders off into the storm and is later found alive. Instead, she is an older, sexually curious teen (early in the film she had spied on David and Amy’s lovemaking) who lures Niles away from the Christmas show for some necking in a barn. When Niles hears his brother calling for him, he panics and accidentally strangles the girl.

Niles, then, is guilty – after a fashion. But the mob that comes chasing after him doesn’t know about the dead girl, nor does David just as he doesn’t know about his wife’s rape. David, the man who number crunches the paths of planets, hasn’t a clue what’s happening in his own house. Consequently, when the siege begins, unlike the book’s George, David is unknowingly protecting a killer (albeit an accidental one).

In a bit of common sense lacking in the book, David calls on the local lawman and it is he – not an interceding neighbor – who is killed outside David’s house. At that point, the fight – for David – goes beyond mere survival. Niles becomes irrelevant, there is no daughter to protect, and what little is left of his marriage is quickly coming apart under the blows of the mob on his front door.

Amy refuses to help David, tries to respond to Venner’s entreaties to let him in, and even attempts to leave. David slaps her, pulls her away from the door by her hair and tells her, “Do as you’re told. If you don’t, I’ll break your neck.”

This is more than a “worm turns” story. This is David, a la Ardrey, defending his property – and that includes his woman; one alpha male (though a latently developed one) fighting off a rival pack. “This is where I live,” he declares to Amy, “This is me. I will not allow violence against this house.”

Despite Peckinpah’s reputation as a master of mayhem, and even with the film’s body count in mind, the filmed siege is more restrained than the one in Williams’ pages. On film, the third act battle takes up about 18 minutes in the 118 minute film, while it takes up over half the novel. Many of the more brutal acts are taken straight from the book: throwing boiling cooking oil (in the book its boiling water) at the invaders, one of the mob shooting off his foot (though in the book, this only cripples), beatings with a fireplace poker (in the book, it’s a baseball bat). Peckinah foregoes the eye-gouging.

Which brings up another sharp departure from the book. David wins not by disabling, but by killing. Standing in his shattered sitting room surrounded by bodies, he says – in a mix of quiet triumph and disbelief – “Jesus…I got them all.” While detractors indicted Peckinpah for equating manliness with violence, there is nothing in the portrayal that either salutes or slams David’s victory; it’s an adamant expression of a plain fact – “We’re violent by nature,” Peckinpah told The New York Times in defending his film, “It’s one of the greatest brainwashes of all times to say we’re not.” Open to interpretation, David’s “win” can equally be taken as disturbing as much as some sort of triumph. In a pure expression of Peckinpah-esque moral ambivalence and ambiguity, David salutes himself for killing five men in defense of a killer and a wife who no longer loves him.

In the novel, come the next day, George is saluted as a hero and becomes the media’s story of the day. His wife, impressed at his manly defense of his family, paints herself unworthy and recommits to him.

Peckinpah and his collaborators struggled to come up with an ending more appropriate to their story all the way through filming. There is no day after, no media salute, no congratulations from the constabulary. David leaves both his house and his marriage in shambles, takes Niles to the car and proceeds to drive him back to the village. Out of a few minutes improvisation in the car between Dustin Hoffman and David Warner, Peckinpah finally came up with what screenwriters refer to as “the button.”

“I don’t know my way home,” Niles says.

“That’s ok,” says David with a small, self-amused smile. “I don’t either.”

Like most of Peckinpah’s protagonists, David has won…at the cost of everything.

Peckinpah did not throw out Gordon Williams’ book. Though re-plotted, the essence of Williams’ story is there. Peckinpah just took it a step further. George’s climactic sense of “I am a man!” now becomes something darker, more primordial, and a less comforting accomplishment. It’s as if Peckinpah took Williams’ seat at the card table, played the same hand, but wagered far more aggressively, raising the stakes and taking the game to another level.

Williams told the story of an emotionally repressed academic who defends his family by falling back on the primal violence within. Peckinpah expanded the thesis, taking out the nobility of defense of family to find the animalistic sense of territoriality and blood lust presumably within every man, ready and waiting to be unlocked under the right combination of circumstances.

The natural argument is, which is better? But that does a disservice to each work; each artist was after something different. Williams’ thriller was primarily looking to thrill, and ultimately it does.

But next to Williams’ nine-day quickie, Peckinpah’s film is clearly the more ambitious, the dynamic between David and Amy certainly more dramatically dense than the soapy sniping between George and Louise, and the film has certainly resonated over time much more strongly than The Siege of Trencher’s Farm, coming to be considered one of the director’s best films; some argue perhaps even his most accomplished.

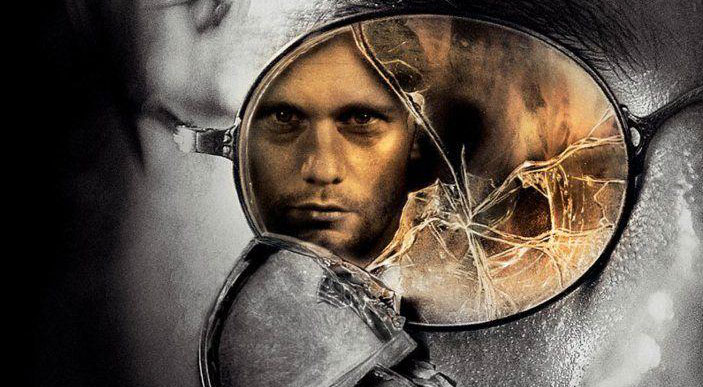

Which certainly presents a hell of a challenge to any filmmaker daring/foolhardy enough to remake it…making Rod Lurie either one of the most daring filmmakers on the scene today, or an incredible fool.

* * * *[vsw id=”7krZZabaC_U” source=”youtube” width=”500″ height=”425″ autoplay=”no”]

Judging a movie only by its trailers is like judging the quality of a restaurant by reading the menu: it hardly compares to actually tasting the food.

Still, if the menu offers nothing but hash and grits, one’s expectations can’t help but be low, and the aroma from Rod Lurie’s kitchen so far doesn’t bespeak of a Gordon Ramsay hard at work.

From his filmography, it’s clear Lurie, a one-time film critic whose loose, instigatory style got him banned from any number of critics’ screenings, is a seriously-intentioned filmmaker. But only with his 2000 effort – the political drama The Contender – has his execution come close to matching his ambitions. Most of his feature credits are nobly-intended misfires like Deterrence (1999), The Last Castle (2001), and Nothing but the Truth (2008). Even with The Contender – easily one of the best big screen political dramas of the 2000s – Lurie copped out with a third act deux ex machina which dumped all over the two hours of taut, adult, halls-of-power drama which had come before. Nor has he ever been able to connect with the mass audience; The Contender, his best performing film, returned just over $22 million worldwide on a $20 million budget.

The question with any remake is, of course, why do it? The power of Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs is that it continues to speak to viewers about the deep-rooted propensity for violence in the human animal, but, at the same time, the original’s plot is firmly anchored in the social turmoil of its time. For all the economic-bred dissatisfactions and disillusionments of today, it’s hard to find a similarly trenchant counterpart to that 60s/70s subtext.

Lurie’s acknowledged plan is to not go back to the Gordon Williams source novel. It is Peckinpah’s movie he is remaking, his view being the original is a strong but “…very imperfect movie…murky…” with room for improvement. Lurie guarantees his remake will be every bit as disturbing and controversial as the 1971 film. But, like relocating the story to the American south, the trailer suggests Lurie may only be making cosmetic changes (and, in true 21st century fashion, amping up the action) while generally staying close to the narrative line of Peckinpah’s film.

It’s still childless David and Amy (only now David is a screenwriter), it’s still a return to Amy’s old hometown, David still hires Amy’s ex and his cronies to repair his garage, and more. In fact, what gives the trailer now in circulation such an unsettling feeling to those who know the original film is just how many of the original’s key points – including specific lines (“I will not allow violence against this house”), images (the impregnable fieldstone farmhouse looking a bit strange in backwoods Louisiana), and actions (the boiling oil; wrestling with a mantrap) are packed into the 2:32 clip. Even the current one-sheet for the movie closely apes the striking image of the 1972 poster.

While Lurie, to his credit, likes emotionally charged adult situations and grand themes, he’s never shown any flair for the kind of moral fog which was Peckinpah’s specialty. Even in The Contender, Lurie’s best work thus far, the bad guys are clearly the bad guys and bad for venal, petty reasons, while the good guys are good because they’re pledged to a higher, greater good. That’s a moral clarity which would have made the Sam Peckinpah of Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid gag, and makes Rod Lurie an odd choice to try to re-bottle Peckinpah’s unique brand of cinematic lightning.

Last year, the Coen Brothers managed the paradox of a remake – in True Grit – which yet felt fresh and original. They went back to Charles Portis’ source novel to find the flavors, the voices, the textures the 1969 original film missed. But the early indications are Lurie’s Straw Dogs may be more like another Peckinpah remake: Roger Donaldson’s 1994 second take on Peckinpah’s The Getaway (1972). Donaldson didn’t go back to the Jim Thompson original, but, instead executed a suffocatingly close redo of Peckinpah’s film, lifting some scenes and dialogue directly from the original which only made Donaldson’s movie look all the more stale and unnecessary.

For Gordon Williams, this is a no-win game. Even if Lurie out-Peckinpahs Peckinpah – or at least comes close to some kind of parity – it’s re-presenting a take on The Siege of Trencher’s Farm Williams has long been unhappy with. One can only imagine how much unhappier he’ll be if Lurie bobbles the ball and turns out only a pallid version of a story Williams already hates.

But that would be a finale Peckinpah would have appreciated; that even when you win…you lose.

– Bill Mesce