Songs of Metal and Flesh

Hellraiser Book 3

Written by Peter Atkins

Art by Dave Dorman, Lurene Haines & Phil Felix

Published by Epic Comics

Music and hell have been closely associated since at least the Middle Ages, when the Catholic Church strictly controlled the use of the tritone, or Devil’s Interval. A wide range of musicians, from Nicolò Paganini to seminal bluesman Robert Johnson, are among those said to have made Faustian bargains to attain their talent and fame. These stories are, by now, so familiar as to be clichés.

Clive Barker wonderfully reimagined hell and deals with the devil with his novella The Hellbound Heart and Hellraiser, his own cinematic adaptation. While the sequels kept coming, to ever-diminishing returns, the initial Hellraiser comic series from Marvel’s Epic imprint remained true to Barker’s original vision.

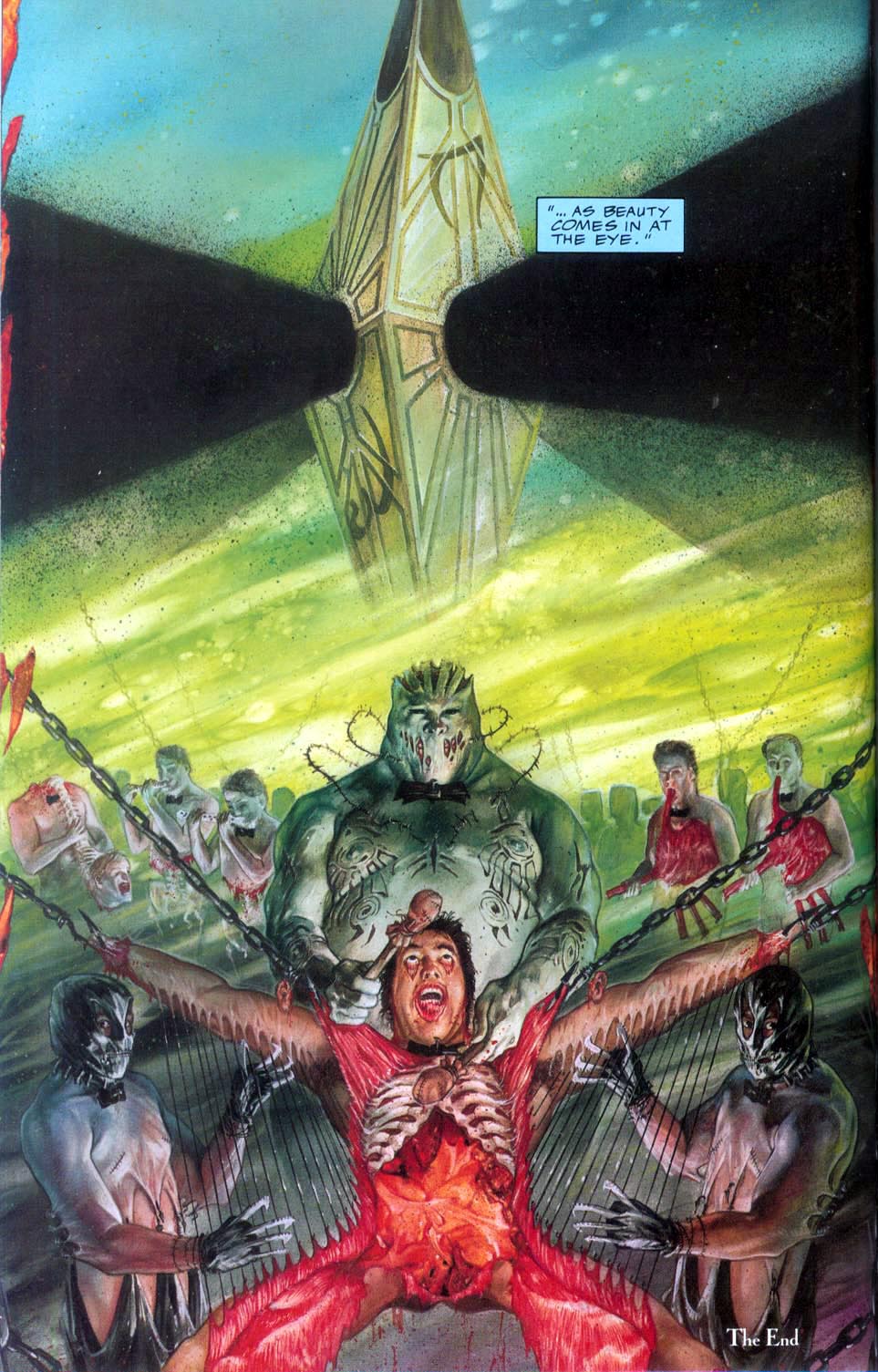

Peter Atkins, screenwriter of Hellbound: Hellraiser 2 (a.k.a the only sequel that matters), used the comics platform to make something new of the “diabolical pact made at the crossroads” trope. “Songs of Metal and Flesh” originally appeared in Epic’s Hellraiser #3 and delivers a very Barker-esque mix of dread, viscera and sadomasochism that manages to be both bleak and queasily beautiful, with art by Dave Dorman, Lurene Haines and Phil Felix that is very much worthy of the writing.

It’s the story of Jason Marlowe who, we learn via his first-person internal monologue, was blinded as a child but enthusiastically embraced the resultant heightening of his remaining senses. He also develops a powerful musical talent and, as Atkins so ably describes, begins to discern “hidden melodies, those mysterious harmonies that I knew circled somewhere between our world and the next.”

Lust and envy bring an end to Jason’s professional musical aspirations and he devotes his time to unlocking those hidden melodies, with the covert guidance of hell. He finds the music is quite literally within him and creates not only the ultimate example of diabolus in musica, but also a gruesome and ironic prison for himself.

The terrible beauty of “Songs of Metal and Flesh” (and this part of the Barkerverse writ large) is rather like the tritone: Dissonance in search of resolution that will never come.