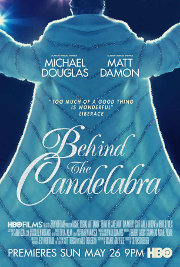

Behind the Candelabra

Written by Richard LaGravenese

Directed by Steven Soderbergh

USA, 2013

Call it what you will, but if Steven Soderbergh is truly exiting the cinematic frontier for a while, Behind the Candelabra marks a very fitting and appropriate departure for the director. Adapted from the autobiographical novel by Alex Thorleifson and Scott Thorson, Candelabra is a rather direct biopic shedding light on the private life of Liberace (Michael Douglas) and his 6-year relationship with younger lover Scott Thorson (Matt Damon). Having known next to nothing about the stage life or persona of the former, Candelabra possesses the sparkling allure we’ve come to expect from Soderbergh, vaulting us backstage and behind the scenes for a closer look at two vulnerable lovers who become masked in their own vanity without a proper road map out.

Aside from the glitz and aesthetic grace of this particular period piece (let’s be honest, Soderbergh shoots the hell out of this thing), most of what makes Candelabra resonate are the close-to-career-best performances from Soderbergh regulars Douglas and Damon. At first, it’s a romance of convenience as the small-town-inspiring-veterinarian Scott makes his way to Vegas and is overwhelmingly won over by the flamboyant showmanship and charisma of Liberace (also referred to as Lee).

As their series of bed and Jacuzzi-side chats wear on, the relationship morphs into something more complicated and vain. And though Scott places heavy insistence on his bi-sexuality (we never actually see him with any women), his allegiance seems to be one of essential love and devotion given the paternal role that Lee takes on. Soderbergh’s commentary on homosexuality is nothing if not appropriate to the period as Lee’s handlers, publicists, and manager (Dan Akyroyd as Seymour Heller) all but wash away any implication of Liberace’s sexual orientation. “People only see what they want to see,” says Liberace early on, signifying perhaps the crux of Lee and Scott’s relationship, and an overarching theme seen throughout the director’s filmograhpy (think Magic Mike and Side Effects).

Behind the Candelabra’s facade of rosiness reaches points of literal decay in its second half as Lee and Scott begin down a path of betrayal and bodily abuse: plastic surgeries aplenty for both and Scott’s drug addiction function as reminders that Scott can’t seem to break out of his “stranger in a strange land” role. It’s in these sequences that Soderbergh’s breathes life into the film – most notably in the dancing camera that captures the convoluted surfaces surrounding Scott’s chaotic state. As we get a clear picture of Lee’s health withering away in the final act (a vivid reminder of Douglas’ real life battle with cancer), the images and shared acts begin to further resonate, resulting in an all too appropriate final shot that should provide Candelabra with some staying power.

With the pedigree involved mixed with its premiere at Cannes, one’s expectations may be a tad too much. If Candelabra does sag, it’s in the screenplay which strictly adheres all too safely to its biopic – friendly mold. But somehow, the director feels all too at home within the confines of this HBO production, a platform in which he could easily thrive in if need be. Soderbergh all too often wins this reviewer over with the casting of his supporting players: Rob Lowe and Nicky Katt show up in small roles, with the former’s absurd physical appearance being an absolute comedic marvel, while Katt is still stuck in the grizzled drug-dealing stoner role which never ceases to grow old. It’s hard not to be seduced by Douglas’ portrayal here, an actor possessing the precise amount of larger-than-life zeal mixed with the inevitable bout of insecurity. But it’s Damon who somehow steals the show as Scott’s trajectory is both predictable and heartbreaking. His role as chauffeur, bodyguard, friend, confidant, and lover is eventually all too taxing; but what makes Damon the stand-out and thematic mainstay is his fight and naïveté against the imminent. Candelabra may come across as standard, but Soderbergh’s characterizations and fanciful flight of emotion proves to be anything but.

— Ty Landis