Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Starring Derrick De Marney, Nova Pilbeam, George Curzon

It is a matter of uncertain serendipity that my first film of the BFI’s Hitchcock season happened to be Young & Innocent, reputedly Hitch’s favourite of his British pictures, now widely considered as the first cohesion of style and substance that displays many of his subsequent iconic motifs and iconography – the incorrectly accused protagonist, the urgent romance, a dash of macabre humor, and of course the intangible plot driver or manipulative McGuffin. If you can parse Hitchcock’s long and exalted career into three core sections – the early silents as the art form’s grammar and genre definitions took shape, the British talkies where Hitch was on the vanguard on a new phase of cinema’s technological transition and the Hollywood era which from 1940 until his death in 1980 marks one of the longest, most profligate artistic periods in the formats history then Young & Innocent is a crucial piece in the central criminal canon, nestled between the clandestine thrills of Sabotage and The Lady Vanishes it prompts numerous smirks of knowing indulgence, as we are witness the evolution of the portly prestidigitators tricks and tropes that were to become crystallised and immortalised in his subsequent, cadaverous masterpieces.

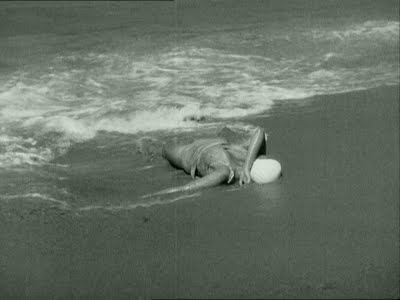

Barely five minutes in and a bloated body is washed ashore to the soundtrack of keening gulls, so clearly we’re in Hitchcock territory after the preceding opening scene which presents us with a blazing argument between a musical drummer (George Curzon) and his soon to be slain, cuckold wife. Spying the corpse dancing lazily in the seas embrace is our unfortunate hero Robert Tisdall (Derrick De Marney) who rushes down to see if he can assist, he spots a raincoat belt drifting next to the body in the low tide of the shore, before swiftly making off from the scene of the crime to alert the authorities – his first mistake. Tisdall is spotted by two women coming over the cliff and their interpretation of his swift exit is somewhat more incriminating, and soon he is facing probing questions from the local Detective Inspector Kent (John Longden). With no clear alibi and coincidently his own overcoat having been stolen from his car some days earlier – fate is never kind in Hitchcock’s universe – Tisdall makes a cunning exit from the clutches of law and order and teams up with the feisty and resourceful local Constables daughter Erica Burgoyne (Nova Pilbeam) as he goes on the run to retrieve his belt and clear his name….

As I have mentioned before I’ve done quite well with Hitchcock’s surviving fifty-three features, out of the American strand I’m only missing seeing one of them (an oversight that will shortly be rectified) and I thought I’d done well with his British talkies, but this was a shock to behold as I swiftly realised that I hadn’t seen Young & Innocent before, therefore I was treated to both a glimpse of both of Hitchcock in crucial metamorphosis and that inalienable sense of accomplishment that we completests experience when achieving a further step forward toward perfection. It’s an early example of the chase narrative as seen in the likes of North By Northwest, Saboteur and is predeceased by The 39 Steps, with our protagonist just one step ahead of the law, accompanied with an initially distrustful love interest, whose suspicions will thaw as the passions and suspense arise. This strong quality, well-preserved BFI print gives rise to some of Hitchcock’s early technical tampering, including some extensive use of model sets, his frequent employment of extensive back-projection and this celebrated early shot,a dizzying crane which is orchestrated with a remarkable dexterity for 1937;

As I said this was quite advanced for its era and I’m sure Hitch could have imparted the necessary story information – that the murderer is in blackface on the stage – could have been signalled through a series of dialogue queries and embezzled with some explanatory cutaways, but where is the fun in that? No, this gives us a sense of sleek, gliding menace as it traverses the narrative space which also proves important for the film’s climax, as we need to know whom is where and when in clear dimensions for this crucial, final turn of the screws.

That said I did find the ending rather anti-climactic by Hitchcock’s high standards, the murderer breaking down into shrieking, guilt-driven insanity but no matter, there is enough to enjoy over the preceding ninety minutes. There are also shards of the psychological complexity that infiltrate the later work, the theme of guilt by accident with Tisdall or guilt by association is clear in the figure of Erica, as she abscond with the criminal who might just be – now how can I put this delicately – who might be getting her engine running as he injects some dangerous glee into her middle class, controlled and demure life, her criminal associations forcing her Chief Constable father to resign his commission, with all the Elektra inflected guilt that such an event engenders, in a scene that Hitch plays more for pathos than perplexity. There is a fine scene as the renegades are sucked into a children’s birthday, the perils of societal norms of politeness and decency trumping their urgent quest, I just love how Hitchcock played with melding the strange and apprehensive with the surface of respectable and normal, polite behaviour, an apt metaphor for the homicides and horrors lurking before the surface, of situating the murderous amongst the mundane, the hostile seeding a pungent trail of anxiety and suspense throughout Hitchcock’s rap-sheet. Young & Innocent is a pastoral Hitchcock, a frothy foam of fun as the waves crashing over the prone and lifeless body that opens the drama, an early seedling of the forest of the fearful that will find full fruition in the gender treachery of the brittle blondes of his later work, where he punished his female eyrines as much as he adored and idolised them.

– John McEntee