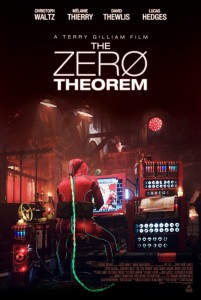

Written by Pat Rushin

Directed by Terry Gilliam

UK/Romania, 2013

In 1983, the final Monty Python film, The Meaning Of Life, was released with a rather ambitious title and intent to discover, well, the meaning of life. Thirty years later, and Terry Gilliam returns to these enterprising realms with his new film The Zero Theorem, a codex volcanic in enthusiasm yet insipid at its core. Terry does good press: he barks an intriguing sound bite, citing that his latest ode to chaos is an “impossible look at nothing,” which is certain to prick the interest of existentialists everywhere. But like that void-gazing ideology, the film is bereft of significance as it wanes and wavers as something of a chore, an extravagant, gelatinous mess of half-baked ideas and pasquinade profundity. Any original film that exists aside the morass of sequels, prequels, comic books, and young adult novel translations renders it welcome, and Gilliam has the chutzpah and insane ambition to wield the medium as some kind of digital seer. But one must operate coherently and pay lip service to supposedly stifling conventions such as plot, transitional structure, as well as tempo and pacing, or your musical odyssey will emerge as a cacophonous, incoherent dirge, which is exactly the final result here.

Christoph Waltz is the bald-headed, eccentric Qohen Leth, an introverted computer wunderkind who babbles incoherent observations and mysteriously awaits an ominous phone call. Ensconced in an Orwellian corporate world, which immediately evokes and suffers from comparisons to Gilliam’s beloved Brazil, Leth is employed by the mysterious oligarch known as Management. His sole purpose is to crack the cryptomaniac code of the titular zero theorem, a mathematical formula whose seismic reverberations would make Einstein’s theory of relativity the equivalent of a match being struck to the Big Bang. Sequestered to his murky home, a burnt-out chapel lurking in a more frenzied area of town, Leth is aided and abetted in his task by a number of exaggerated grotesques: his snooty and slimy supervisor Joby (David Thewlis) the seductive Bainsley (Mélanie Thierry) and Bob (Lucas Hedges), the teenage son of the puppet master of Management.

Fans of Gilliam’s exuberant lunatic vision and jaunty unbridled style will find some succor in his latest, but as with many of his films, any sense of rationality or a solidified commentary has been lost in the translation from his imagination to the screen. Perhaps that’s the point, given the impossibility of ever understanding our chaotic and complex universe and maybe so, but on a simple, visceral level, the willful lapse in logic only serves to alienate rather than provoke. Visually, as expected, the film is striking, but a perceptible gloss is not enough to feed on when wrestling with some of the biggest themes possible—the nature of consciousness, life after death, how our scientific constructs attempt to make order from chaos, the incomprehensible scale of comprehensible reality—and heralding the introduction of wacky characters with Dutch framing is now a cliché in his work. The Zero Theorem has all the trappings of a slightly confused spirit railing against the modern world, finger-wagging and tutting at the functions of MMORGs, of web pornography, of social media and indoctrinating surveillance, weakly lampooning these phenomena without weighing their potential ancillaries, the satire unfocused and unfulfilling.

Alongside his trademark compositional clutter, Gilliam also stuffs the film with plenty of cameos that can lasso you back to the film when attention wanders, including Ben Whishaw, Peter Stormare and a slightly more sizeable role for Matt Damon. There are also a few blink-and-you’ll-miss-them faces embedded in the omnipresent advertising infrastructure, which comes across as a bargain-basement Blade Runner. The purpose of this casting appears to be allowing the audience to stay awake should they drift into sleep, but the film just veers wildly from scene to scene, all sound and fury, signifying nothing. Even Tilda Swinton, an actress who is almost universally beloved for her breadth of ability and chameleonic skills, is supplied with perhaps her worst role to date, a scene where, as an online psychiatrist with a Scottish brogue, she breaks into a stuttering rap scene. It’s a massive embarrassment. Gilliam has cited The Zero Theorem as the final part of his so-called dystopian satire trilogy, stretching from Brazil to 12 Monkeys. Considering the fanbase and adoration those films have accrued, this unforgiveable lapse drags the trio deep into the negative zone.

— John McEntee