Take three of why I wanted to write about Bigfoot: Bigfoot is an avatar of extra-human nature.

That is to say in the last two parts, I fibbed a bit for simplicity’s sake. Claiming Bigfoot has no cultural baggage is both true and false; he has no mythology and no permanent being, yet he does stand in for something in a thematic sense. He is unknowable, yes, malleable as well, but also an idea made somewhat more concrete- giving legs to a concept in order to express the abstract through a story. Bigfoot, in all his hairy glory, continually and perpetually represents an idea of “nature” (a term I take issue with, but for simplicity’s sake will use to mean all existence outside of that which is explicitly “human” or anthropocentric). He is, much like Swamp Thing, an avatar of the earth and of life. There is no Bigfoot media that does not see him as a representation of the “wild” and of all that is external to modern human existence.

This is not contradictory with Bigfoot’s other aspects because what nature is and what it means can vary perpetually and to an almost unlimited degree. Depending on who you ask, “nature” can mean a plethora of different things, many of them contradictory but all signified by the same term. In some films, Bigfoot embodies entirely a romantic (in the literary sense) view of nature- harsh, consuming, dark, and frightful, the birthplace of all sin and destruction. He is the reason humanity left the woods behind for grayer pastures. He is a demon, he is violence, and he is fear. This is certainly his most common rendering, which is not surprising- more than two hundred years out, western culture still festers with this romantic attitude towards the world outside of that which humanity directly controls. It is something to be tamed, understood, and kept at arm’s length; even environmentalist and conservationist concerns see the world outside of humanity as something to be controlled and manipulated, even if it is valued. Humanity does not reside within it. Bigfoot represents, to an industrial society, the anger of nature and the wrath of the Other. He is an avenging force, come to push humanity back into the dark ages.

But this aspect holds little interest and not much to add; it is too easy, pat, and common. It is the major narrative of the world at large, and as such it is explicated in the majority of art you see, and as such its exegesis only repeats, ad nauseam, the narrative already understood. Its resonance lies in human alienation from the natural world. Hell, even the creation and manipulation of the word “natural” shows a complete severance of civilized human culture from its surroundings. It exists purely to separate humanity from the world at large, and it refuses to even consider humanity as part of this world. I am more interested in a different kind of natural portrayal, one that Bigfoot movies often have an unusually keen ability to work through and build upon. A more radical vision of Bigfoot sees him as less of an avenger than a reclaimer, a dark and horrific reminder of the dangers of forgetting unity and oneness. That’s not to say he’s non-violent- certainly, nature as it is known can hardly be said to be non-violent- but rather that he exists to destroy that which is alienated. Think of him as a cross between a simplified Old Testament God and a very radical environmentalist; that which cannot understand its place in the world has to be punished for its disobedience and ignorance of the universe at large.

In this reading, Bigfoot exists not to encroach upon or consume, but to course-correct and signify. He is The Forest writ large upon the minds of those engaged in industrial society. Every Bigfoot movie I’ve seen- and I’ve seen nearly every one commercially available outside of Harry and the Hendersons– involves the encroachment of human civilization upon some stretch of vast wilderness, disrupting the temperament and balance of the setting. Whether this invasion is through a massive construction project or the minor annoyance of a few campers on some sort of “quest for the truth”, the results and reactions are the same. Bigfoot comes, Bigfoot destroys, Bigfoot reclaims. In many of these, a character is introduced that has lived in Bigfoot country for years and years without serious harm, a streak broken, of course, by the entering of industrial society- of alienated society- into the circumstances. Bigfoot is not the cause of violence, the introduction of a mindset is; by itself, there is no evil. The woods are not dark and filled with demons, as so many artists have portrayed it. The evil is brought into nature, and nature works to reject it. Bigfoot is the white blood cells in an inter-connected and rich world, hunting down and destroying the diseases of exploitation and human self-obsession whenever they sprout up. Bigfoot exists as nature’s defense and reaction to violence, not as malice itself.

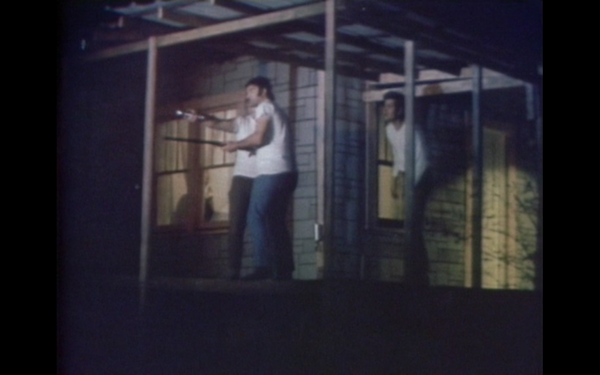

This view can be found most clearly in a very odd and unique little film called The Legend of Boggy Creek. Released in 1972, The Legend of Boggy Creek is a strange horror/mockumentary movie that follows a series of short stories by locals of a town in Arkansas called Fouke. Part real accounts, part fictionalized sensationalism, part small town portrait, and part drive-in hootenanny, it presents itself as a documentary and snakes its way through an overarching narrative with a group of vignettes detailing encounters with the Fouke Monster, sometimes called the Southern Sasquatch. In the stories, we see dramatized versions of people’s encounters with this wild man, often taking place on the outskirts of the rural area, on the edge of where the farming ends and the swamps begin. They escalate until the final portion of the film, where a family defends themselves from the monster over the course of several nights. Throughout, the audience hears from our narrator and ostensible director, a man who encountered the creature as a child and remembers to this day his terrible, haunting cry.

Now, outside of the unusual format (a choice so odd I’m still not sure after multiple viewings how I feel about it), it sounds a bit run of the mill. People encounter Bigfoot, people flee from Bigfoot, horror ensues and dark nights in the forest become foreboding and dangerous treks. But it is a scene oddly out of place that opens the film up, a scene that, until reflection, seems to make little sense in the context the movie has provided. The audience meets a man who has lived deep in the woods entirely alone for nearly twenty years. He seems like a prime target for the beast, but that’s the kicker- the man is the only person in the film who expresses a lack of belief in the monster. He’s never seen it, and he thinks the whole idea is hogwash. So, in essence, his story adds nothing to a film about the horrors of Bigfoot; we see his shack, he says he’s never seen the creature and that it doesn’t exist, and we leave. But it comes into focus when one removes the traditional romantic narrative of nature and places in the other one provided; the movie is about the horrors of men and the distancing of a town from its surroundings, not the horrors of Bigfoot. The old man who lives by himself, content and happy deep in the heart of the demon’s territory, has never seen it because it has no reason to visit him. Bigfoot (or the Fouke Monster, in this case, although the two are effectively one in the same) has no reason to attack a man who has not removed himself from the world. Bigfoot’s battlegrounds are the edges of the town, the places where nature meets the separated world of industrial civilization. The only danger posed is for those who choose to exile themselves, for those who live in a way that lies to them and says they exist outside of the natural world, that they are not part of it. The only ones at risk are the alienated.

From this vantage, the scene ties in clearly and fits exactly in place. The film- less a horror movie than an offbeat portrait of a small town losing something of its familiarity, character, and past- strives to point out the deadliness of this approach. The severance is the danger, not Bigfoot exactly. He is merely the guilt and suppressed memories of a time before this distancing took place. Bigfoot is a sort of manifestation of the collective unconscious, given power and form through a fear that the way humanity has chosen to exist might be wrong. The narrator of The Legend of Boggy Creek muses late in the film on the creature’s loneliness, and this offhanded comment brings a melancholy tone to the film because the audience knows Bigfoot is nature’s avatar; as it is destroyed, its cry thins out until it is solitary and fragile. This is why Bigfoot continues to resonate so strongly in a culture that very rarely would choose to enter his domain, and as such should have little fear of him; Bigfoot is both the romantic terror of nature and a collective industrial terror of our own progress. He is the dangerous ghost of a dead and dying earth, haunting humanity with its own destruction, weakness, and sin.