Please note that the following piece contains spoilers for the final act of Blow Out.

Taken at face value Blow Out, Brian De Palma’s 1981 film, is a nifty and tightly wound little thriller. It starts to run into some trouble, however, when compared to Michelangelo Antonioni’s seminal counter culture classic Blowup (1966), the film that most inspired it; there is arguably more artistic impact to Antonioni’s film. It helps when the viewer realizes that Blow Out isn’t a full-on remake, and it would be wrong to describe it as such; rather, it is an alternative interpretation of Blowup‘s major concerns. Both films have their merits and both films have become classics in their own right.

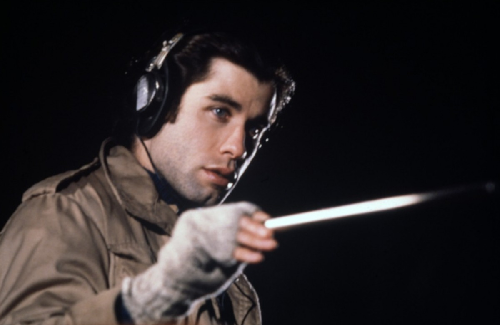

Blowup is the story of a frivolous fashion photographer (David Hemmings) in 1960s London, who believes he may have unwittingly photographed a murder while taking pictures of lovers in a park. Blow Out takes place in Philadelphia and follows a sound technician, Jack Terry (John Travolta), who records evidence of what seems to be an assassination attempt involving a governor and a call girl, Sally, (Nancy Allen) the latter of whom survives the ensuing car crash late at night; Jack’s presence in his film’s park at the time of the crash is due to him capturing sounds for a new production.

Blow Out was also inspired by Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), and is much more focused than Blowup on the central mystery that drives the film. It is exceptionally clever in handling that mystery, and in a lesser director’s hands a narrative juggling political assassination, a prostitute love interest, and a serial killer would either be a terrible mess, full of clichés, or both; De Palma, however, creates a film that is perfectly executed and challenging. It also manages to show a portrait of real grief and guilt. Its climactic scenes are wrenching, particularly the very last in which Jack listens to the final moments of Sally’s life. It’s torture, pure and simple, and after the emotionally draining journey De Palma puts viewers on during the film, that look on Travolta’s face as he covers his ears is one final gut punch.

That’s really where Blow Out differs from Blowup. Antonioni’s film is beautiful, extraordinary really. The entire film is a great technical achievement and it’s a cultural landmark. Antonioni inventively experiments with character, camera angles, you name it, but ultimately Blowup is a cold and detached movie; the argument could be made that it is meant to be. We’re never meant to have a relationship with the photographer. We’re simply meant to examine him, hold him at arm’s length. You never feel connected to him, you never feel emotionally wrecked by his failings or vulnerabilities, mostly because we’re never given the chance. Antonioni isn’t presenting us with a portrait of defeat like De Palma is.

One of the things that is so surprising and so deeply felt when you watch Blow Out and then compare it with Blowup is those undertones of grief; you really feel all of that devastation for Jack and Sally. Add in elements of the Watergate conspiracy, the JFK assassination, and the Chappaquiddick incident, and you have yourself a heady film that brims with nervousness, paranoia and fear, De Palma giving us voyeurism at its worst and most destructive; all of those themes are found in Blowup as well, but with different contexts and cinematic flair. There is also the sense of helplessness that imbues the film. Both Jack and Sally grow into people who want to help and change things, wanting to do the right thing only to have their desires turn around and destroy them. You never get that sense with the photographer in Blowup. More than anything it feels like he wants to save and protect only himself.

As evidenced, comparing Blow Out and Blowup on a surface level isn’t too difficult a task, but each film stands on its own and serves its own purposes. Blowup is best viewed as a a watershed moment for counter culture media, while Blow Out stands as not only one of the high points of Brian De Palma’s career but also one of the finest thrillers ever made.

— Tressa Eckermann